It`s Culture, Not Morality

advertisement

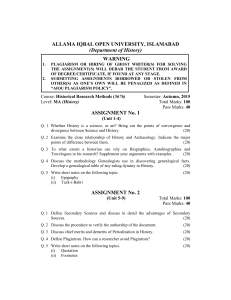

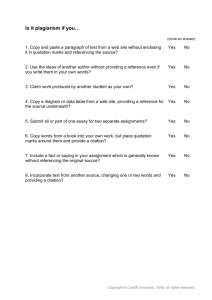

It's Culture, Not Morality February 3, 2009 What if everything you learned about fighting plagiarism was doomed to failure? Computer software, threats on the syllabus, pledges of zero tolerance, honor codes -- what if all the popular strategies don't matter? What if the anger teachers feel -- as they catch students clearly submitting work they didn't write -- is clouding their judgment and making it more difficult to promote academic integrity? These are some of the questions raised in My Word! Plagiarism and College Culture, in which Susan D. Blum, an anthropologist at the University of Notre Dame, considers why students so frequently violate rules that seem clear to their professors. The book, about to appear from Cornell University Press, is sure to be controversial because it challenges the strategies used by colleges and professors nationwide. In many ways, Blum is arguing that the current approach of higher education to plagiarism tries to impress students with technology and make them afraid of what could happen to them. Blum wants higher education to embrace more of a hearts and minds strategy in which academics consider why their students turn in papers as they do, and the logic behind those choices. The book arrives at a time that many professors continue to voice frustration over plagiarism. Services such as Turnitin have grown in popularity to the extent that it is processing more than 130,000 papers a day. At the same time, however, there has been some backlash against this approach. Professors are saying that they fear they are missing a chance to teach students about how to write because they are focusing so much on finding the cheaters. Those who want to understand the ideas in the book may want to note the title; it's no coincidence that Blum wrote about college "culture," and not "ethics" or "morality." Although she did use "plagiarism" in the title, she faults colleges and professors for failing to distinguish between buying a paper to submit as your own, submitting a paper containing passages from many authors without appropriate credit, and simply failing to learn how to cite materials. Treating these violations of academic norms the same way is part of the problem, she writes. Blum's book is based on her research on the way colleges try to prevent plagiarism and the way students view college, knowledge and the writing process. Many of the ideas come from the 234 undergraduates at Notre Dame who participated in in-depth interviews. The students were given confidentiality and the procedures for the interviews were approved by Notre Dame's institutional review board. Blum had originally planned a similar study at a less competitive college, but didn't have time to finish it. She said she thinks there may be some differences in attitudes, because part of the dynamic at elite institutions is a student expectation that they will earn A's and succeed in everything -- an expectation that she said may not be present elsewhere. In terms of explaining student culture, Blum uses many of the student interviews to show how education has become more an issue of attaining credentials and getting ahead than of any more idealistic love of learning. She quotes one student who admits, “…knowledge is important Retrieved on April 6th, 2010 from http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2009/02/03/myword. to me…and to move on the next step, whatever it is…is also important."Students looking for the "next step" may not care as much as they should about actual learning, Blum suggests. Then there is the student concept -- or lack thereof -- of intellectual property. She notes the way students routinely ignore messages from colleges and threats of legal action to share music online, in violation of business standards of copyright. As with plagiarism, she notes, the student generation has embraced an entirely different concept of ownership, and students feel no hesitation about downloading music they haven't purchased. She also notes how much students love to quote from pop culture or other sources -- feeling pride in working into conversation quotes they never invented -- in a way previous generations wouldn't have done. "Student norms contrast with official norms not just because of this proliferation of quoting without attribution, but because students question the very possibility of originality.” Blum writes. At the same time, she notes, students are less likely than previous generation to distinguish between formal and informal writing (think of the importance, to students, of instant messages). Thus, rules about attribution are seen as silly. So where does that leave the academic who -- like Blum -- wants to see students do their own work and learn proper techniques of citation. First, she said that colleges need to admit that their current, law enforcement approach, isn't working and isn't necessarily appropriate. "It undermines our whole raison d'être. Are we there as police? Are we there as adversaries or to serve as models for our students? If we are aiming to get our students to love our subject, I don't think this law enforcement approach is going to get us to our goal." However, faculty members do have a role in promoting academic integrity, she writes. In her conclusion, she describes the importance of talking frequently with students about the value of higher education and learning (aside from professional advancement), and the need for classes to regularly consider the nature of originality, of appropriate citation, of doing one's own work and so forth. In those discussions, she writes that professors need to move beyond their views of these issues. For example, professors should talk with their students about why they tend to value books (and read books) less than their professors did. On citation, faculty members shouldn't be afraid to admit "that the rules are somewhat arbitrary" and that not all of what is called plagiarism is equally wrong, she writes. "Just as we distinguish between taking a grape at the supermarket and stealing a car, we don't want to lump together all infractions of academic citation norms," she writes. In her classes, she said in an interview, it means that she talks about her expectations for academic work, but always tells students they can raise questions. On major papers, she tends to require "steps along the way," so that the ability or temptation of buying a completed paper is diminished. "We need to have a lot more sympathy for students, but we don't have to accept plagiarism or say that it's OK," she says. — Scott Jaschik Retrieved on April 6th, 2010 from http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2009/02/03/myword.