Making a presentation

advertisement

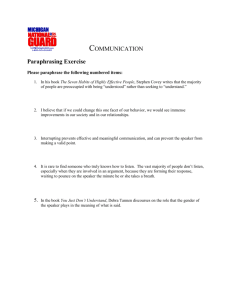

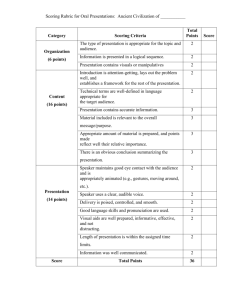

Making a presentation Alaric Maude The comments below are designed to help postgraduate students with their presentations at conferences, but some of their supervisors could also benefit from thinking about what makes a good presentation. The ability to communicate through speaking is a valuable skill, both in employment and in the rest of life, and it is a skill that is worth practising. It is also a different skill to writing – listen to someone reading a paper aloud and you will see that what works as written communication doesn’t always work as oral communication. What makes for a good presentation? The aim of a presentation is to communicate something – an idea, a proposal, your research topic, your findings, or inspiration – to an audience. So what aspects of a presentation seem to assist communication? Structure It is easier for people to understand something that has a clear focus, so explain the purpose of your paper. A continuous stream of facts is impossible to understand unless they form a story or an argument. Create a structure by, for example, posing a question and developing an answer to it. Tell listeners what your structure is after you have introduced your topic or question. Provide them with a road map. But don’t spend too much time on this at the expense of your main message. Identify the major points clearly. Keep it simple, with only a few main points. Your listeners will struggle to absorb large amounts of detailed information. Make sure that the opening and conclusion of your presentation fit together. Delivery Talk naturally (but not colloquially) – verbal communication is different to written. We comprehend better when people talk to us as Don’t read from a text – either use notes, or use your written text only to remind you of each point. In an oral presentation you talk to your audience, not read them a speech. Are you using language and rhythm that is natural to the spoken word or are you sounding like the text of a formal document? (A stilted, unnatural delivery usually occurs when you present dense information by reading it aloud.) (Merritt 2003, p. 80) 1 Choose your words to match your audience. In many academic areas it is difficult to avoid technical terms for which there is no alternative, but if you are talking to people outside your own speciality then think of how to express your thoughts in language they will understand. In particular, avoid giving nontechnical words a meaning that is not in the current edition of the Macquarie Dictionary, such as ‘foreground’, ‘discursive’ and ‘decentred’. Don’t rush – 100 words per minute is enough, as listeners can’t absorb your message if you go at a faster rate. Don’t be afraid of pauses, of silence – these give your listeners time to catch up or to think about what you are saying. Breathe deeply, not just in the upper part of the chest. This affects the quality of your voice as well as the clarity of your thinking. Look at your audience. Involve everyone so that they focus on you and what you are saying. Speak clearly. Remember that a low-pitched voice can be hard to hear. A particular danger is dropping your voice at the end of a sentence. Adjust the volume of your voice to the size of the room and the size of the audience. Learn to project your voice to the back of the room. Vary your intonation. A monotone delivery is boring. Use variations in your voice to highlight important points. Avoid meaningless words (sort of, stuff, um, like). Avoid distracting mannerisms (see more on this below). Keep to time. Have a strong finish (summarise main points, have a clear conclusion, show relevance or implications of what you have found). Learn from people you think are good public speakers. Using PowerPoint PowerPoint is a very powerful tool, but has some traps for the unwary. Here is some advice from a professional. Set-up: Ensure the projector and computer are working well ahead of the presentation. Screens: Adjust room light; too much gives slides a washed-out look. Common look and feel: Set up basic rules in the software’s slide master and apply them to all slides to ensure a professional presentation. Colour scheme: Be subtle. A garish combination can be distracting. Less is more: Keep the number of words on each slide to an absolute minimum. ‘You should be using the slides to illustrate or emphasise your point, not to give all the information.’ Special effects: Don’t go overboard with flying text or revolving logos. Images: Check that photos are of sufficiently high resolution. Talk to the audience: Always face your audience. Do not read the slides to the audience, as the audience can read faster than you can speak, and will then stop listening to you while you to catch up to them. Handouts: Have handout copies of your slides available after the meeting, or to produce if the technology lets you down. 2 Consider the 10-20-30 rule: A PowerPoint presentation should have no more than 10 slides, take no longer than 20 minutes, and contain no font smaller than 30 point. Font size depends on the size of the meeting room, so make sure your text is clearly visible from the back of the meeting room. Source: Summarised and adapted from The Australian, ExecTech, 7 February 2006, pp. 4-5. Answering questions Good answers to questions can greatly improve your presentation, because they can clarify areas where your listeners may not have understood you or may disagree with you. Answering questions is also a skill. Make sure that you and the audience understand the question, if necessary by repeating or rephrasing it, and answer clearly and concisely. This is particularly a problem when questions come from the front of the room, and the presenter then gets into a private conversation with the questioner, thus excluding half the audience from hearing both the question and the answer. And don’t be afraid to say that you don’t know the answer. Confidence It is natural to be nervous, but anxiety can lead you into making mistakes, like talking too fast. What can you do to increase your confidence? know your subject; be prepared; be very familiar with the room in which you are presenting; and remember that you are not the only nervous speaker in the group. Further advice For more extensive advice, see Hay 2002, chapter 8. Note also the comments from Merritt below. At this point, therefore, it is probably necessary to consider how we communicate. Very simply, verbal messages are transmitted through the mediums of words, voice and physical use (body language, gestures, facial expressions and eye contact). Words are the very core of the message. Words are our thoughts and feelings in action, articulated in language. That is where the power of the spoken word lies. Once we have spoken, we have committed our thoughts and feelings to another person. However, it is through the mediums of voice and physical use that the subtle cues of communication are delivered. The voice allows the listener access to a richer understanding and interpretation of the words. On a purely technical level, the appropriate use of the human voice allows the listener to hear what is being said because the voice is at the right volume. It allows the listener to be able to follow the sense of what is being said because the delivery is at the correct pace. It encourages the listener to listen sensitively because the correct tone of voice is being used, and it allows the listener to understand because of the clarity of articulation. On a more imaginative level, the appropriate use of the human voice allows the listener to follow 3 the details of the message by means of subtle signposting through shifts in pitch, inflection and intonation, and by the effective use of pause. Physical use allows the listener immediate visual access to the intention of the speaker’s message and indicates the speaker's commitment to the message and to the audience. At its best, it powerfully communicates physical presence, appropriateness of gesture and facial expression to the intention of the message, and the inclusiveness of eye contact. In fact, research has found that voice and physical use are the most significant indicators of the message and that the verbal component of the message is the least significant. Words carry approximately seven per cent of the message, while the voice carries 38 per cent and physical use 55 per cent of the message (Drummond, 1993). These are unsettling findings. If words are our thoughts and feelings in action, then surely it is in the words that the power of the message lies? The reason why the research shows that words (the thought content) play a minimal part in the message received by the listener is quite clear. When we are bombarded by a variety of stimuli, which is what is happening when we are listening to someone speaking, we focus on the medium of greatest density, that is, where the most information is coming from. If more information comes via the voice and/or physical use than the words, it is highly likely that the listener will focus attention on one or both of those areas. For example, you are standing up delivering a formal business presentation. You’ve prepared the material, the PowerPoint display is in place. You begin to speak. Without being aware of it, you start swaying aimlessly as you are speaking. Because of this physical action, your gestures and gaze begin to lack focus, your thoughts start to ramble and your voice becomes less energetic in its delivery. Your sentences fade away before you have finished them. If you continue to do this, the audience will start watching you—and your purposeless physical actions—and begin focusing on your flat delivery. Very soon they will be distracted from the intention of your verbal message. At this point, depending on how busy they are in their own minds, they will have an excuse to escape into their own worlds rather than staying in the present and hearing your message. As the speaker, you will have delivered a set of words and because of this you will have assumed that understanding of what you have said has taken place. However, more likely, the listeners will leave the presentation with a completely different bundle of information from what you had intended. They may walk out with the impression that you were a restless, remote speaker or that you were nervous and self-conscious or, at worst, with no lasting impression at all of what you said during the presentation. As we have seen, the body and the voice can be very easily cluttered with distracting behaviours, and these become glaringly obvious when we speak in more formal environments. Following are some of the many distracting physical and vocal habits of speakers: collapsed, retreating stance, which generally indicates that the presenter does not really want to be there nervous lifting up and down on the heels (the policeman’s hop), which may convey that the presenter has not settled into the presentation environment clamped hands, often in front of or behind the body, which strips the presenter of the power of gestures and makes them appear stiff and remote 4 frozen arm syndrome, where one arm is glued to the side of the body or thigh and the other arm is free to gesture in only a very limited way, inhibiting engagement with the message presenter finding their notes, or the ceiling, or a dead spot behind the back row, or the view out the window, or the space in front of their feet, or the PowerPoint screen far more interesting than the faces of the audience (Such a presenter does not give generously to their audience. They make eye contact with everything but the people in the room, so that the audience is often left feeling that there has been no sense of commitment on the presenter’s part to engage them with the message.) restricted breathing caused by nervousness, resulting in an urgent delivery of the presentation (In this situation, an unnatural speaking rhythm—sometimes staccato—often emerges, impeding the smooth delivery of the presentation. Because the presenter feels as if they are running out of breath, the pace of speaking increases and the delivery becomes rushed rather than considered.) distracting tone in the voice, making it difficult to listen to for a long period of time (At the end of the presentation, the listener may remember the sound of the presenter’s voice rather than the sense of what has been said.) dull monotone delivery, again resulting in the detail of what is being said being sabotaged tightening of the shoulders, neck and jaw caused by tension, which results in a very thin vocal sound, making the words colourless and ineffectual tension in the jaw, which leads to tension in the face, with the result that the facial expression becomes fixed, inhibiting the subtle cues present in a change of facial expression as thought shifts. If you recognise any of these vocal and physical habits, it is highly likely that the impact of your presentations is being seriously affected. Your words will be missing the mark because of unnecessary clutter in the vocal and physical communication mediums. The challenge is to ensure congruence in the transmission of the three messages so that what is being said is totally supported by the vocal and the physical. When you achieve this, there will be consistency rather than erraticism in your communication with your audience. Then, and only then, will you truly communicate with them. (Merritt 2003, pp. 4-8) References Hay, I. 2002, Communicating in geography and the environmental sciences, 2nd edn, Oxford University Press, Melbourne. Merritt, L. 2003, Talking the talk: communicate with persuasion, panache and passion, Choice Books, Marrickville. 5 6 Criteria for Assessing Presentations The IAG gives awards for outstanding presentations by postgraduates at the Institute’s annual conference. These are the criteria used by the assessors 1. Was the topic and purpose of the presentation clearly explained in the introduction? 2. Was the presentation well structured, and was this structure explained in the introduction? Was material presented in a clear and logical order? Were the main points clearly identified? Was there an appropriate finish/conclusion to the presentation, and did it correspond with the introduction? 3. Was the delivery clear and the speed appropriate? Did the speaker avoid reading from a prepared text? Did the speaker use appropriate language and fully formed sentences? Did the speaker maintain visual contact with everyone in the group? Did the speaker avoid distracting mannerisms? 4. Was effective use made of visual aids, such as PowerPoint? 5. Did the speaker keep to the time limit? 6. How well did the speaker handle questions? 7. How effective was the presentation as a means of communication? 7