A National Survey of the Academic Minor and Psychology

advertisement

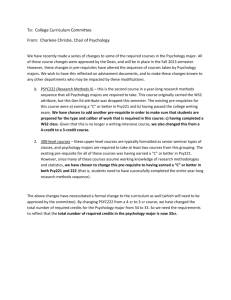

A National Survey of the Academic Minor and Psychology Carolyn Stache Baron Perlman Lee McCann Susan McFadden University of Wisconsin—Oshkosh Brewer et al. (1993) recommended the collection of curricular information to support evaluation of undergraduate psychology programs We gathered basic information on the psychology minor, including national patterns of requirements and recommendations, chairperson opinions about the psychology minor as an academic program, and the minor areas of study that students with psychology majors are advised to select. Surveys were sent to 400 psychology departments; 275 (69%) returned surveys were usable. Discussion focuses on the structure of the minor, the need for advising minors, assessing the minor, and the type of attention psychology departments could give the academic minor, including the minors they recommend for their majors. The terms major and minor were first used in this country at Johns Hopkins University in 1878 (Dressel, 1963; Payton, 1961). The major was defined as a cluster of related subjects (a specialization), and the minor was to be a broadening experience—a lesser cluster (Rudolph, 1977). Most American universities followed Johns Hopkins’ cue and used the terms major concentration and minor concentration. Although this curricular structure became common practice, little research has been conducted to determine its prevalence, structure, and effectiveness. Ideally, breadth in a college education is obtained through general education and liberal arts courses, although students may never appreciate the ways these courses contribute to their education. Depth is normally acquired through the academic major, often a professional specialization. The minor is truly a lesser cluster. It functions as a student’s second specialization and academic program of depth (the first is the major), while increasing the breadth of education. However, we have no data on the educational gains that result from having a minor; that is, we do not know what and how much is learned (Halpern, 1988). Dressel and De Lisle (1969) examined curricular requirements during the 1960s using the catalogs of 322 institutions to assess breadth, depth, and skills in liberal education. They found that more than 50% of the institutions required both a departmental major and a minor for undergraduate students; as the 1960s progressed, however, only about 25% of the institutions required both. Levine (1978) noted that minor requirements were generally half those of the major. In 1978, the minor was required by only 6% of the bachelor’s programs but was an option at 38% of 4year undergraduate programs. Levine obtained these data from the Carnegie Council on Policy Studies in Higher Education, which surveyed 25,000 faculty, 25,000 undergraduates, and 25,000 graduate students on a national level. Levine found that many students obtained a minor, even though it was not required, and observed that students appeared to be electing a minor area of concentration as career insurance” (p. 37). Our experience suggests that many students are interested in a minor not only to increase employment opportunities but also because they like the subject matter and/or believe a minor assists in admission to graduate school. Although little is known about the academic minor in general, nothing is known about the nature of the psychology minor. The APA sponsored the 1991 National Conference on Enhancing the Quality of Undergraduate Education in Psychology, after which Brewer et al. (1993) suggested the need for more information on how many psychology programs offer minors, how many students are enrolled, and what requirements exist. The conference Steering Committee recommended to the APA that more communication about teaching and curriculum was needed, including “a national database on 2- and 4-year programs in psychology to support the ongoing national evaluation of undergraduate programs in psychology” (McGovern, 1993, p.253). Faculty who review, plan, and change academic policies and curricula in psychology, or who advise students on selection of academic minors, have no baseline data to guide them. Halpern (1988) addressed the need for and purposes of data collection for assessing student outcomes for psychology majors. She noted the potential of such data for improving the quality of education and the learning process. In our research that follows, we identify national patterns of requirements and recommendations for the psychology minor as an academic program, report faculty opinions about various facets of the minor, and document the minor areas of study that psychology majors are recommended or required to take. The purpose of this research is to provide data and generate questions and discussion about the development and maintenance of quality academic programs in psychology. Method Instrument Based on the first author’s reading of university catalogs and a review of the relevant literature by all four authors, a three-part survey was developed to gather information on requirements and recommendations for and opinions about the psychology minor. The survey also inquired about minors for psychology majors. The 27-question survey was pilot-tested by sending it to three professors active in higher education and psychology curricular research. Section 1 of the questionnaire collected general information on the public or private status of institutions, highest degree offered by institution and department of psychology, the academic calendar system, and the approximate number of psychology majors and minors enrolled in each department for academic year 1991—92. Section 2 asked whether each college or university required all undergraduates to complete a minor; whether departments offer a minor in psychology and, if so, how many credit hours or courses are required for the psychology minor and major; and whether psychology departments require or recommend that psychology majors have an additional minor area of study and, if so, in what curricular areas. Data were gathered on whether and in what ways the academic minor is structured (e.g., required core courses, number of credits, field placements, and advising). The last section was titled “Value of the Psychology Minor” and asked respondents to rate nine items on a scale ranging from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (5). These items were based on issues and concerns derived from the literature review and our own experiences. They focused on offering an academic minor, fiscal implications of the academic minor, class sizes, competition between students with psychology minors and majors for classroom seats, the contribution of a minor to a well-rounded education, depth of education, attracting students to become psychology majors, employment options, and the value of the psychology minor. Sample and Procedure In 1986-87, the APA listed psychology departments in tabular form for a federal report. There were 1,202 departments in the country offering a psychology major leading to a bachelor’s degree; 1,012 of these graduated more than five majors annually. Universities were chosen randomly from the latter, and 534 catalogs were reviewed. Of these, 400 (74.9%) offering the traditional psychology minor were surveyed. Those institutions offering only a topical or individualized minor were excluded. (The topical minor is a combination of courses from 2 or more departments that the student uses to create an individualized minor course of study.) Along with the survey and prepared return envelope, each department chair received a cover letter that included the option of asking a more knowledgeable colleague to complete it. Catalog data on requirements for the psychology minor were pre-entered on each survey, and chairs were asked to correct any errors. The data were pre-entered to create a complete data set of 400 entries and to maximize response rate. Pre-entered data included the required number of psychology credits for the major and minor, whether the minor has a set structure, the required core courses, and how many upper level credits were required. Based on a classification scheme from the American Council on Education (1987), university size was coded as “small” (1 to 4,999 students), “medium” (5,000 to 19,999), or “large” (20,000 or more). Size includes both undergraduate and graduate students. Catalogs for 284 small universities were read; surveys were sent to 207 of these universities, and 137 were returned. Catalogs for 187 medium-size universities were read; surveys were sent to 145 of these universities, and 106 were returned. Catalogs for 39 large universities were read (there were fewer large universities to be sampled); surveys were sent to 24 of these universities, and 16 were returned. Results Of the 400 surveys distributed, 283 were returned (71%). Eight were not usable; three respondents said they did not have a psychology minor, contrary to their institutional catalogs, and five checked the pre-entered items without completing the survey, leaving 275 (69%) returned and usable surveys (and 400 for pre-entered items). Respondent Data (n = 275) Of the responding institutions, 140 (51%) are public and 135 (49%) private. The institutions are predominantly (81.3%) graduate level as defined by highest degree offered. However, 48.7% of the psychology departments offer only the bachelor’s degree. Of the public institutions, 28 (21.4%) were small, 87(66.4%) were medium, and 16(12.2%) were large. For the private universities, 109 (85.2%) were small and 19 (14.8%) were medium. A t test showed that public (M = 11,008) and private (M = 3,516) universities differed significantly in size, t (192) = 8.51, p < .001. The number of undergraduates at the responding institutions ranged from 400 to 30,400 (M = 5,744, median = 3,500, mode = 2,000). The number of graduate students ranged from 12 to 8,000 (M = 1,390, median = 900, mode = 1,000). Total number of students ranged from 420 to 36,600 (M = 8,073, median = 5,842, mode = 12,000). Almost all institutions in the study are small or medium size. The number of psychology majors reported ranged from 10 to 1,400 (M = 258, median = 160, mode = 100). The most frequently required number of credits for a major ranged from 51 to 40 (M = 36.5, median = 35, mode = 30). Some universities require a specific number of courses for the academic minor. Such data were converted to credits by multiplying each course by 3. Trimester and quarter calendar systems were converted to semester credits by multi-plying by 2/3. Pre-entered Data (N = 400) At least one pre-entered item was changed by 108 (38.6%) of the respondents. Most frequently changed items were the number of psychology credits required for a bachelor’s degree and whether the department minor required upper level credits and, if so, how many. These changes occurred because many catalog requirements were ambiguous, particularly in these areas. The figures resulting from altering pre-entered data (275 returned surveys) differed little from the pre-entered data (400 original surveys). For example, the pre-entered mean (M = 19.49) for required minor credits was almost identical to the corrected data (M = 19.79). The pre-entered mean (M = 36.13) for required psychology credits for the bachelor’s degree was similar to the corrected mean (M = 36.52). Thus, the pre-entered data were judged generally accurate and used for data analysis when a survey was not returned. Data were corrected as necessary when a survey was returned. The Psychology Minor Forty-two (15.4%) institutions require students to have a minor in some subject area; 231 (84.6%) do not. The number of students who are psychology minors ranged from 2 to 677 (M = 73, median = 40, mode = 50). About 50% of the departments studied have 32 or fewer students minoring in psychology. Most psychology minor programs are structured. Core courses ate required at 258 (93.8%) institutions. All minor programs require a minimum number of total credits, ranging from 12 to 63 (M = 19.8, median = 18, mode = 18). The most frequently required credit range was 16 to 20 (57.8%), and the next most frequent range was 21 to 25 (23.6%). The number of credits required for a minor in psychology continues to be about half the number required for a major. Specific course requirements are common. Introductory psychology is required by 89.1% (n = 245) of the departments, 20% (n = 54) require statistics, and 18.2% (n = 49) require research methods. Upper level credits are required at 144 institutions (52.7%), ranging from 3 to 28 (M = 10, median = 9, mode = 9). For those requiring upper level credits, a majority (52%) require that half of the total units for the minor program of study be at the upper level. There are few other requirements or provisions for the academic minor. One department (0.4%) required and 36 (13.4%) recommended a field placement. Advising for students with a minor in psychology is not readily available, with only 68 (25.1%) departments requiring a minor adviser. Of these, 60 (76.9%) require a psychology faculty member as adviser. A relatively high percentage (n = 74, 26.9%) do not know who their psychology minor students are or how many they are educating. Respondents’ comments on the surveys included, “We don’t track these in our department,” “Many students do not officially list a minor until they have finished it,” and “It is impossible to know since records are not kept for the minor.” Comparisons of public (51%) versus private (49%) institutions yielded no significant differences regarding the minor. Opinion Questions on the Psychology Minor The majority of respondents (84.3%) strongly agreed or agreed that they would include a minor in a new curriculum. Reasons for agreement with this statement became clear in other responses. Many (78.7%) agreed or strongly agreed that the minor provides a well-rounded education, and 81.6% agreed or strongly agreed that the minor adds more educational depth. A clear majority (69.6%) also said that the minor may attract good students to the psychology major. The data are less clear on whether the minor provides more employment options (55.7% thought it did, and 42.3% were neutral). Finally, 82.4% of the respondents strongly agreed or agreed with the statement, “I value the minor.” Respondents’ reactions to opinion questions do not strongly support our assumptions about problems with the minor. Most respondents (53.8%) were not concerned about fiscal situations affecting minor quality, although 23.6% had such a concern (22.6% were neutral). Similarly, a majority (56.8%) did not believe that minors increase class sizes that are already too large, but 22.1% agreed with this statement (21% were neutral). Nearly a majority (48.9%) agreed (32% disagreed, 20.1% neutral) that minors compete with majors for seats. We analyzed opinions of respondents in public and private institutions. There were significant differences between respondents from public (M = 3.13) and private (M = 3.86) institutions on the statements “minors increase class sizes,” t (268) = 5,37, p < .001, and “minors compete with majors for seats” (M = 2.83 for public, M = 3.80 for private), t (269) = 6.93, p <. 001. Respondents at public universities (larger, more majors) more often agreed that minors increase class sizes and compete with majors for seats. Moreover, there was a high correlation (r = .76, p < .01) between the statements “minors increase class sizes” and “minors compete with majors for seats” for all respondents (public and private institutions). Psychology Majors and the Minors They Take Fifty-four (19.8%) psychology departments require their majors to take a minor- 12 more than the 42 departments in colleges or universities with an institutional requirement for an academic minor. In other words, of the 233 departments in a college or university with no institutional requirement for an academic minor, only 12 (5.2%) require a minor. Despite all the arguments favoring a minor, and despite its popularity, few institutions and departments of psychology require one. In addition, 58 (21,2%) departments recommend that their majors take a minor, and 161 (59%) have no preference. In all, 73 different minors were recommended, many with similar foci, so they were combined into four categories. Table 1 presents the frequencies and percentage of respondents recommending specific disciplines in each category (mathematics/science, applied/professional, social sciences, and humanities), with the most frequent being biology (n = 125), sociology (n = 92), and business (n = 76). Almost all respondents listed more than one recommended minor. Table 1. Frequencies and Percentages of Respondents Recommending Minors for Psychology Majors Subject No. % Science/mathematics Biology Computer science Math, statistics Chemistry, pre-med 125 32 24 16 45.4 11.6 8.7 5.8 Cognitive sciences Applied/professional Business Social work, welfare, etc. Criminal justice Communication, speech, sign language Education, special education Human services, counseling, chemical dependency Health care/wellness Gerontology Family science, human ecology Christian education ministry, youth work Evaluation research Pre-law Humanities English, literature, creative writing Humanities Art, drama Spanish Peace studies Women’s studies Social science Sociology Anthropology Political science, urban studies Economics, social science 2 0.7 76 27 18 17 17 10 7 4 4 3 1 1 27.6 9.8 6.5 6.2 6.2 3.6 2.5 1.5 1.5 1.1 0.4 0.4 22 22 6 2 1 1 8.0 6.0 2.2 0.7 0.4 0.4 92 8 8 2 33.5 2.9 2.9 0.7 Discussion Description of the Academic Minor The traditional minor is offered at 75% of 400 universities, but only 15.4% (n = 42) require it. Dressel and De Lisle (1969) found that by the late 19 60s, only 25% of universities required a major and a minor. Levine (1978) noted that a major and a minor were required at only 6% of universities. We found that 15% require both, an increase since the late 1970s, possibly reflecting a different sample of institutions. Most universities offer additional specialization through a minor program of study, but they require basic general education with specialization only in the major area of study. When our respondents were asked if their department required or recommended a minor in another discipline for their majors, some replied, “We recommend a broad liberal arts education rather than additional specialization, [a curricular minor],” “It has nothing to do with us . . . it has to do with the student’s needs and interests,” “We don’t care, and “Depends on future application of major.” Historically, the minor has been viewed as a broadening experience for students. Most respondents would offer a psychology minor for students with majors in other disciplines if developing a new curriculum, and they agree that the minor helps students obtain a well-rounded education, adds depth, and assists in graduate school admission. Why more departments do not require an academic minor for their majors is unknown. Most universities structure the psychology minor by number of credits, number of required upper level credits, and/or type and number of required core courses. Brewer et al.’s (1993) recommendation is followed; the majority require the introductory course. Other requirements vary. Many require students to take a course or courses from a given topic area, such as methodology, but allow choice within topic areas. Brewer et al. recommended requiring one methodology course. Advising Although most departments structure their academic minor, few departments provide advising to students who minor in psychology. Without faculty input, minors may choose any psychology course meeting the credit requirement. Most respondents are concerned about the quality of the minor. In response to the question about quality and the university fiscal situation, one said, “No matter what the fiscal situation, we would want to offer a ‘quality minor.’” Another mentioned “class limits to ensure quality instruction.” However, 26.9% (n = 74) were unable to report who their psychology minor students are or the number of minors their department educated. Such data are necessary if a department is to advise minor students, know which courses they are taking and why, and determine if the academic minor is meeting the department’s goals and quality standards. Assessment of the Minor Defining academic quality is difficult. Halpern (1988) described several approaches to assessment of the psychology major that could be used to assess the quality of the academic minor. She noted that institutions may differ with regard to the assessment they deem most appropriate, but she suggested that six general areas should be examined: knowledge base, thinking skills, language skills, information gathering and synthesis, interpersonal skills, and practical experience. Departments need to decide whether these six areas, so critical to the quality of the major, also apply to the minor. We suspect that few departments have ever defined their goals for the minor. There are no data to support the positive attitudes respondents have about the academic minor in psychology. Data collected from students and alumni would enable us to learn if the minor is as valuable and useful as faculty believe it is. Although students may find a psychology minor interesting, the question remains: “. . . what can you do with it after you graduate?” (McGovern & Carr, 1989, p.52). For some students, a minor may just happen. Perhaps many accumulate credits because they like psychology and end up with a minor largely by accident. One is struck by the wide variety of and lack of consensus on recommended minors for psychology majors. The lack of agreement among psychology departments regarding the minors their own ma-jars should take may reflect a similar lack of consensus in other departments. Thus, one cannot assume that students are electing to take a psychology minor because their major departments recommend it. Although Levine (1978) suggested that students take a minor as “career insurance” (p. 37), there are no data to support this idea. Does a minor in psychology assist graduates in obtaining a job and/or advancing in their careers? Assessment of the minor should include efforts to determine the academic majors of students who minor in psychology. If a trend emerges showing that these students come primarily from majors like criminal justice or social work, one might surmise that the psychology minor directly supports the major and is related to career goals. However, if no such trend appears, then the job relevance of the psychology minor may involve interpersonal skills and/or critical thinking about behavior. Because the study of behavior is central to psychology, it is hard to imagine any job for which psychological insight would be irrelevant. Assessment of employers’ perception of the psychology minor should be a part of ongoing research on the minor. Clearly, much more work is needed to assess the minor. A good model for such research is the work of McGovern and Carr (1989) on surveys of alumni who majored in psychology. These studies need not be extensive; departments could easily gather these data for their own use. Departments’ Attention to the Minor Departments may want to pay more attention to the minor. If faculty members believe strongly in the idea of a lesser concentration and the benefits of a minor program of study, they may want to require a minor for their psychology majors. Departments in colleges or universities that do not offer a traditional minor could determine if one should be instituted. An active discussion on offering or requiring a minor could help some departments clarify their values and goals for the minor. A second discussion could focus on the minor that departments offer to majors in other disciplines. Although most departments structure the minor as a mini-major, only the introductory is required for most students with a psychology minor. If departments examine their specific goals for the minor, they may decide to require more courses for their minors or develop emphases or tracks to serve specific majors. A third discussion may benefit psychology departments in public institutions struggling to maintain seats and a reasonable timetable fat graduating their majors. Should they limit the number of students who can minor in psychology? One solution is to save seats for majors in psychology courses; students with a minor would register later for the remaining seats. Has a department ever limited its minors by requiring a minimum grade point average for minors, a procedure some departments use for allowing students to become psychology majors (Perlman & McCann, 1993)? Shepperd (1993) described strategies and a model for reducing the number of majors; both are applicable to the problem of too many minors. Although some departments may need to limit the number of students enrolling as minors, others may need to promote the option of minoring in psychology, especially if they are concerned about declining enrollments of psychology majors. The current biopsychosocial models of psychology may support nearly any major, and a psychology minor could be valuable to students majoring in diverse disciplines. If departments had data on what disciplines provide the most psychology minors and on why these students minor in psychology, then departments could develop model curricula for the minor. For example, if alumni studies in these disciplines were similar to those reported for psychology majors (i.e., interpersonal skills are required more than scientific skills on the job; McGovern & Carr, 1989), departments may want to advise psychology minors to take psychology courses that help with learning about and relating to other people. A well written handout covering these issues for psychology minors could be useful to these students when selecting courses. Psychology departments also need to examine their positions regarding the minors their own majors take. Emphasis on mathematics and natural sciences for a minor area of study for psychology majors (see Table 1) may be misplaced, except for graduate school aspirants. Psychologists believe that their discipline offers a scientific understanding of behavior and teaches students to (a) think critically about the causes and consequences of behavior (b) reject stereotypes, and (c) appreciate the different causes of behavior. How well majors or minors learn these lessons is unknown. Nevertheless, given the emphasis on assessing the quality of educational outcomes (Halpern, 1988; Halpern et al., 1993), departments may be forced to learn more about the long-ignored academic minor in psychology. References American Council on Education. (1987). American universities and colleges. New York: de Cruyter. Brewer, C. L., Hopkins, I. R,, Kimble, G. A., Matlin, M. W., McCann, L. I., McNeil, 0. V., Nodine, B. F., Quinn, V. N., & Saundra. (1993). Curriculum. In T. V. McGovern (Ed.), Hand-book for enhancing undergraduate education in psychology (pp. 161-182) Washington DC: American Psychological Association. Dressel, P. (1963). The undergraduate curriculum in higher education. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Research in Education. Dressel, P., & De Lisle, F. (1969). Undergraduate curriculum trends. Washington, DC: American Council on Education. Halpem, D. F. (1988). Assessing student outcomes far psychology majors. Teaching of Psychology, 15, 181-186. Halpem, D. F., Appleby, D. C., Beers, S. E., Cowan, C. L., Furedy, J. J., Halonen, J. S., Horton, C. R, Peden, B. F., & Pittenger, D. J. (1993). Targeting outcomes: Covering your assessment concerns and needs. In T. V. McGovern (Ed.), Hand-book for enhancing undergraduate education in psychology (pp.23-46). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Levine, A. (1978). Handbook of undergraduate curriculum. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. McGovern, T. V. (Ed.). (1993). Handbook for enhancing under-graduate education in psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. McGovem, T. V., & Carr, K. F. (1989). Carving out the niche: A review of alumni surveys on undergraduate psychology majors. Teaching of Psychology, 16, 52-57 Payt(on, P. (1961). Origins of terms “major” and “minor” in American higher education. History of Education Quarterly, 1, 57-63. Penman, B., & McCann, L. (1993). The place of mathematics and science in undergraduate psychology education. Teaching ofPsychology, 20, 205-208. Rudolph, F. (1977). Curriculum. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Shepperd, J. A. (1993). Developing a prediction model to reduce a growing number of psychology majors. Teaching of Psychology, 20, 97—101. Notes 1 We thank our university’s Graduate School for support in conducting this research. We also thank the anonymous reviewers and Charles L. Brewer for their thoughtful and insightful observations and assistance, as well as the many department chairs and faculty who took the time to complete our questionnaire. 2. The questionnaire, detailed tabular data, and reprints may be obtained from Baron Perlman, Department of Psychology, University of Wisconsin—Oshkosh, Oshkosh, WI 54901.