Emotional Glue - New Mexico School for the Blind and Visually

advertisement

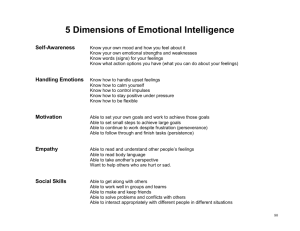

From: Smith, M., (2010) Symbols and Meaning, APH. (appendix) Emotional Glue—Making Meaning Stick The best and most beautiful things in the world cannot be seen or even touched. They must be felt with the HEART. HELEN KELLER Teaching is both an art and a science. The ideas and strategies in this book focus on the technology, or the “science” of teaching as described by the developmental psychologist and researcher Piaget, who gives many cognitive and rational reasons for the need to connect meaning with experience. Helen Keller’s quote, however, reminds us that intuition and feeling , as well as thinking and concrete experience, are essential components of education. Recent research in the area of social cognition shows that what every grandmother knows may be true: Emotional connection is an important foundation for learning. Children who have high “emotional IQs” are more likely to grow into adults who have the cognitive flexibility and perspective-taking skills which are important for academic and vocational success (Gibbs, 1995, Goleman, 1995, Hobson, 2004). Without important visual cues, the blind or visually impaired child is at a real disadvantage in the area of social and emotional development (Sandler and Hobson, 2002). The visually impaired child may not receive information such as facial expression the use of body positioning in communication, or the give and take nature of nonverbal turntaking routines. She may miss incidental learning about relationships which sighted children obtain through their eyes— the way a smile looks, how a mom kisses dad versus how mom kisses a baby, what does a game of hide and seek look like, and how can you tell who is”it”? . Even the more accessible auditory and tactile modes of input can be confusing if they are not paired with visual information—blind children are often uncertain and awkward about how to interpret and use tone of voice, volume, and touch to convey feeling. Children learn these social-emotional skills, as well as many other important symbolic and cognitive skills, best when they are emotionally engaged with their partners. Most of us learned our ABCs, our “times tables” and how to read our first words within engaging social contexts—by singing a song together, reciting for a supportive partner, or looking at a book as our parent reads to us under the covers at night. Through the “emotional glue” generated by our interactions with our partners, these skills were “stuck” in our minds. The emotional glue is so strong that the information is permanently imbedded. Compare this to information which we learn in isolation—the dates of important Civil War battles, the procedure for solving quadratic equations, the capitals of all of the states. (Most of us would have a difficult time recalling these facts, which we learned while studying alone or saying them back to ourselves. ) From: Smith, M., (2010) Symbols and Meaning, APH. (appendix) How can I tell if we’re connecting? This seems easy enough, until you start to interact with students who have hard-to-read faces and bodies, and insufficient language to give you clues. A good starting place for reading the child’s responses to you is the conventional one--“Find the Smile.” When getting to know a child, or beginning a relationship, the initial goal might be to “find the smile,” rather than to achieve compliance or performance of specific behaviors. This can be tricky though. The smile is not always a reliable cue to the child’s mood or feelings about the interactions. Many kids, especially those with “quirky” nervous systems smile (or even laugh) when they are anxious or upset. Some children smile unintentionally, while others never smile, even when they are quite content and engaged with another person. So it is important to be a careful observer of your student, and to observe how he is communicating his feelings about being with you or the activities you have brought to him. For some students , body orientation is a good cue—the student who turns toward you rather than away from you may be saying, “OK, I like to play with you better than being alone.” The student who reaches toward you or the object which you offer may be conveying a message of acceptance. Participation is another important way that students can tell you they understand the activity and are willing and interested in connecting to you. Don’t expect immediate participation, however. For many students, all new activities signal challenge and trigger avoidance. A student who has built a trusting relationship with his teacher or parent may be more willing to watch a new activity passively at first than to flee the area; however, true active participation may only occur after repeated passive exposure to a new game or activity. If you are using hand-under-hand support to introduce the child to the activity or the materials, does the child willingly follow your hand, or do you have to “re-connect” with her frequently to maintain the physical support? Some students have highly idiosyncratic signals for connection and avoidance—one student communicated pleasure and enjoyment by wiggling her feet. This was not apparent to the teacher until the student’s sister commented on it. Last, but not least, remember that YOU are 50% of the connection! Pay attention to your own “emotional barometer” and notice how you are feeling during your time together. Do you laugh and smile during the activity? Do you wish the activity was longer, or do you keep looking at your watch and wondering when you can stop? Do you feel it was worthwhile to have spent the time playing with the student? Sometimes, do you feel amazed that you are actually paid to do this job because it is so much fun?! From: Smith, M., (2010) Symbols and Meaning, APH. (appendix) Deaf-blind educator and researcher Jan VanDijk calls this ability to read and engage with students “It.” (personal communication, 2007). He feels that some parents and teachers quite naturally “have It,” while others need to practice in order to “get It.” Spend some time learning about your student and how to read her heart and the “it” you share. OK—now I understand “It”—how can I use “It”? Now that you know how to recognize and measure the connections you have with students, you probably want to find ways to use this information. 1. Teach social-emotional skills as a separate subject area. Spend time every day doing some activities in which the primary goal is to teach relationship-building skills. Use a standard framework for selecting goals and objectives in the area of social and emotional skills. It is important to have a developmental hierarchy of skills and a philosophical framework to profile a student’s social strengths and needs, rather than using a deficit model to select specific skills to teach. With a curriculum based model, progress can be planned and monitored more rationally. One framework that may be helpful for students with skills below the seven year level developmentally is presented in the book Better Together: Building Relationships for students with Visual Impairment and Autism (Hagood, in press). This curriculum uses four domains for evaluating and selecting socialemotional skills development: Social Interaction Communication Social Cognition Emotional Development Another good framework for students at the early linguistic level is the SCERTS Curriculum for children with autism (Prizant, 2006) Reframe and rename activities—In this book, Ms. Smith has done an outstanding job of reframing the focus in many activities in this book. By calling them “games” instead of “tasks” and by reframing the interactions, both the teacher and the student approach the activity in a more social and interactive way. An activity labeled as a “task” or “work” suggests a focus on independence, with the adult directing, evaluating and prompting the student, and the primary goal being completion of a task. On the other hand, when an activity is labeled a “game” or “play,” it suggests that it will be fun, and that it will be cooperative with more equity, with the primary goals involving connection and joint attention. In their presentations on Relationship Development Intervention, Gutstein shows excellent examples of parents reframing everyday activities such as “going to get the mail,” or “sweeping the floor” to reflect their focus on building relationships. In the parents’ minds (and those of their children), the activity is “special time with mom” rather than daily chores (Gutstein, presentation 2006). From: Smith, M., (2010) Symbols and Meaning, APH. (appendix) Build connection rituals into your day. These are brief interactions in which the primary message is unconditional acceptance. In Becky Bailey’s book, I Love You Rituals (2000), many examples of these types of connection activities are described. The rituals can be as simple as “pat-a-cake” or as complex as writing a story together. However, they must be activities that both you and the student enjoy doing together and which make you look forward to being together. When building these rituals, it may be important at first to incorporate the child’s obsessive interests or repetitive play or language. A child who repeatedly flaps her hands in front of her face might be a good candidate for a manicure ritual that occurs every day after lunch. A student who removes his shoes might enjoy a “This little piggy game” or a game with finding a surprise in the sock, or a foot rub before putting his shoes back on. A child who enjoys making up silly words may enjoy a “guess the definition” game in which you take turns making up words and using them in sentences. Whatever connection rituals you decide to make, give them a name, schedule them into your daily routine. The more detached and isolated the child is, the more connection rituals he will need to keep him engaged and build a relationship. Teach social skills classes or schedule time for social games. In these activities, higher functioning students may practice specific social skills using role play, or may provide support or suggestions for peers facing emotional challenges. Students with more limited language skills may perform more active or concrete social activities to help them appreciate and understand the importance of being together and sharing joint attention, such as “Freeze Dance.” One student plays the keyboard and the other(s) dance until the piano player stops the music, when they must all freeze. Additional movements can be added, including falling down to a glissando, jumping up and down to rapid staccato notes. “Passing energy,” Clasp hands in a circle, and ask one person to make a simple sound (e.g. “mmmm”), squeeze his partner’s hand to “pass it to him”, then the partner makes the sound and squeezes the hand of the next person in the line. “Show and Tell,” A student brings an item to show and describe. Others in the group ask questions or produce comments about the object. 2. Use social-emotional connections as a foundation for learning in other areas. Often, the primary goal of a lesson is in another area such as mobility, fine motor skills, or self-care. Social-emotional skills can be used to “make meaning stick” when the primary goal of instruction is in another area. Students will learn new skills best when they are emotionally engaged with an adult or peer partner. If you have recently taught a student to engage with you playing a “pick a hand— my voice has a surprise for you!” game (Hagood, in press), you might try teaching matching or object association skills using this game as a foundation. The dialogue could go like this: From: Smith, M., (2010) Symbols and Meaning, APH. (appendix) Teacher: Joey, my voice has a surprise for you—teacher holds up 2 fists, close to her face, Joey: (smiles, remembering the game) reaches for teacher’s left hand. Teacher: Opens hand and makes a loud “whoop- whoop” sound1 Joey: laughs. Teacher: Now, Joey, my HANDS have a surprise for you. Can you find something in my hand that goes with this? (shows Joey soap). My hands have a surprise for you—pick a hand (teacher puts button in one hand, and washcloth in other hand Joey: Picks teachers left hand (button) Teacher: No, not a button, try again Soap and____? Joey: Picks other hand (washcloth) Teacher: Opens hand with washcloth) Whoop whoop—you found the washcloth—goes with the soap (This activity could also be used to teach tactile symbols and their association with specific objects) Another example, for a teacher trying to teach concepts of high and low, fast and slow, left and right. Use the finger play “Two Little Blackbirds” as a foundation for learning directional concepts. Teacher helps child learn the following finger play sitting either behind, beside or in front of child Two little blackbirds sitting on a hill, one named Jack and one named Jill (help child put fists out, with thumbs up) Fly away Jack, Fly away Jill, (Help child fly hands behind back) come back Jack come back Jill (Help child return hands to front). Teacher laughs and gives the “birds” a little kiss. After the child has learned this fingerplay and begins to anticipate or imitate the movements, the teacher can change it to a context for learning directional and movement concepts, naming the birds, “fast and slow”, “high and low” “left and right.” For the child whose connection with you has involved word play, in which you make up crazy words together and assign them meaning, try building some rules into the game to teach him phonological awareness. For example, “pig latin” involves moving the first letter to the end of the word and adding an “-ay” (“cup” becomes “up-cay”). Other variations might include “frog latin”, in which an “ibet” is added at the end of the word (“table” becomes “able-tibet”). Or you might try “spoonerisms,” in which the initial sounds in two words are reversed (“hot coffee” becomes “cot hoffee.”) Tickle games can be expanded to include instruction in naming body parts, sequencing, pronoun use (“I tickle your ____” “You tickle my ____”) From: Smith, M., (2010) Symbols and Meaning, APH. (appendix) Highlight the affective information which naturally occurs in the game or routine. The feelings which incidentally or purposefully occur in natural contexts deserve your teaching time and energy. Remember that the student who has visual and multiple impairments may not incidentally learn social skills such as reading partner responses. Use consistent affective vocal tone to model specific feelings. Avoid sarcasm or flat tone. Allow the child to check your face or body tactually during designated times, so that she will have a chance to see what a smile “looks like,” how your body is oriented when you are ready to interact. Plan to imbed affective instruction which has been taught directly during “social skills lessons” in other activities during the week. For example, if the lesson for the week is on “using body position to stay connected,” look for opportunities to teach, reinforce, and assess this skill throughout the week— o during music, give the student praise for orienting toward the teacher during instruction, o in the cafeteria, help the student go from table to table to try to determine which students are connected and which are eating alone, based on their body position. o Remind the student before an activity begins that one of his goals is to stay connected with his body. Practice this before going into the art room, and tell the art teacher that he is working on this. 3. Teach the language of feelings and relationships. It is important to help the student learn to read and express feelings using conventional, easy-to-interpret forms which others will be able to interpret without having a “translator.” Remember how long it took you to learn to read your student’s heart? Others may not be so patient or committed in the future. Often, it is suggested that the language of emotions is “too abstract” or “too high level” for the child who is just beginning to learn language. However, research shows that feeling and connection words are often included in the language of the preschool child, and that those children who have the most feeling words in their vocabulary are least likely to demonstrate aggressive behaviors in kindergarten (cite this). The following strategies may be helpful: Affective vocabulary can best be taught using “hands on” active-learning approaches that are described in this book for other concepts. Pair the words for important feelings and relationship concepts with real-life activities as they occur. Model language rather than asking questions about the child’s possible feelings. For example, say “I bet you felt excited about going to the birthday party!” instead of “How did you feel about going to the party?” Talk about how YOU feel in specific situations and give the reason for your feelings in simple language that helps the child connect causes with feelings, e.g. From: Smith, M., (2010) Symbols and Meaning, APH. (appendix) “I felt frustrated because I couldn’t find my keys.” “I felt proud when you sang on the stage.” (Although there are 2000 words to describe feelings in the English language, most adults rely primarily on 3 pairs of polar opposites to describe their own feelings—happy/sad Teach language that describes relationships and cooperation, not just individual feeling words, e.g. “together,” “group,” “partners” “connected/ disconnected” “friends,” “game” “team..” Use pretend play and sensorimotor play activities to demonstrate emotional intensity, and to practice calming techniques in non-stressful periods. The “emotion meter” shown on the following page, is a helpful tool for some students for teaching identification of one’s own emotional level. It can be taught using a pretend play activity in which the child goes on a row boat ride with the teacher, encountering exciting and sometimes scary animals and an out-of-control thunderstorm along the way, with each rated a slightly higher number on the emotion meter scale. Once the child has learned the scale in this pretend play scenario, it can be applied to other activities as well, including physical activity (slow jogging is a #30, walking #10, and wild running #100), loudness of a piano keyboard, relaxation during yoga. Use tactile symbols to represent feelings. In the tactile symbol system used at TSBVI, feeling vocabulary is distinguished from other symbols by mounting the symbols on a heart shaped background. The feeling words can be used to help describe a student’s feelings when they are engaged in an activity, then the student can read a “sentence” or “experience story” in which the feeling symbol is paired with specific activity and/ or person symbols (e.g. “Jake scared dentist on Tuesday,” “Joey excited hamburger lunch”). Another tactile symbol activity might involve organizing a storage book of symbols based on the student’s feelings about specific people or activities (all of the people that make the student feel “happy” on one page, and all of the people or activities that make a student feel “frustrated” on another page.) 4. Use strategies to remind yourself, your student, parents and other staff members of your commitment to understanding and growing the relationship with the student. Be supportive—make your presence signal reward not demand. You want students to be happy when they hear you coming, rather than dreading the interaction or engaging in avoidance behaviors. True, some kids have had bad experiences with teachers in the past that they will bring to their interactions with you, but overall, your goal is for them to be happy to see you each morning. If you continue to see avoidance behaviors, rethink the way you are interacting with your students From: Smith, M., (2010) Symbols and Meaning, APH. (appendix) Use the“Yes-and” approach to interactions and ideas, which is often utilized by improvisational comedy groups (McGehee). This approach involves accepting whatever idea the child offers, even if the child did not intentionally offer the idea butg simply performed a distinctive behavior. For example, when planning a shopping list, the student may belch and laugh, and you may say, “You are so smart Jimmy, we need to remind everyone to belch in the van before we go into the store!” . Work towards building a balanced relationship (things you like, thinks I like, things we both like). Realize that relationships, like people, grow developmentally. At first, you may put in much more emotional energy than you get back from your students. Look for the small things that the student does that make you feel good about being with her, and try to reinforce those and shape them into prosocial behaviors or language. As you become familiar with a student, you should begin to expect him to participate in activities that YOU enjoy, instead of only doing the things they like to do. As the student’s teacher, you are teaching him more than just how to read, talk, or feed and dress himself. You are also helping him learn how to have relationships with friends, family, and caregivers which will be essential in future job, home and social situations. REFERENCES Bailey, Becky A. (2000) I Love You Rituals (New York: Harper Collins) Sandler AM and Hobson RP (2002) On engaging with people in early childhood: The case of congenital blindness. Clinical Child Psychology & Psychiatry. Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence. New York: Bantam Books. Gibbs, Nancy (1995, October 2). The EQ Factor. Time magazine. Web reference at http://www.time.com/time/classroom/psych/unit5_article1.html Greenspan, Stanley I. and Wieder, Serena (2006) Engaging autism: Helping children relate, communicate and think with the DIR floortime approach. Cambridge, MA. Da Capo Press Gutstein, S. and Sheely, R. (2002) Relationship development interventions with young children. London: Jessical Kingley Publishers Gutstein, S. and Sheely, R. (2002) Relationship development intervention with children, adolescents, and adults. Hagood, Linda (2008) Better Together: Building Relationships with People who have Autism and Visual Impairment . Austin: TSBVI. From: Smith, M., (2010) Symbols and Meaning, APH. (appendix) Hobson, R. P. (2002) The Cradle of thought: Exploring the Origins of thinking. London: Macmillan Hobson, Peter (2005) Why connect? On the relation between autism and blindness. In Linda Pring (Ed.) Autism and Blindness. New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons Publishing McGeHee, Les (2006) Plays well with Others. Austin, Tx: Dalton Publishing Prizant, B., Wetherby, A. Rubin, E., Laurent, A.., Rydell, P. (2005). SCERTS model: A comprehensive educational approach for children with autism spectrum disorders. Vol I: Assessment, Vol. II: Program planning and intervention. Baltimore: Brookes Publishing Company. Sonders, S. (2003) Giggle time: Establishing the social connection. London: Jessica Kingsley Wolfberg, P. (2003) Peer play and the autism spectrum: The art of guiding children’s socialization and imagination (Integrated Play Groups field manual) Shawnee Mission, KS: Autism Asperger Publishing Co. From: Smith, M., (2010) Symbols and Meaning, APH. (appendix) Emotion Meter Number Emotion Feels like a 100 Out of Control thunderstorm 90 Mad shark 80 70 Upset or Getting Silly dragon Worried or Excited alligator Relaxed or Happy ( fish 60 50 40 30 20 10 Sleepy ) From: Smith, M., (2010) Symbols and Meaning, APH. (appendix)