An Ethical Decision

advertisement

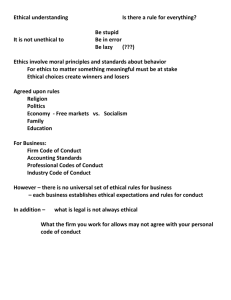

RECOGNIZING AND RESOLVING VALUE CONFLICTS: AN ETHICAL DECISION MAKING PROCESS FOR PHS LEADERS Introduction The “Operating Principles” of the Providence Health System recognize that efforts to further Providence’s mission may lead to value conflicts (also discussed as “dilemmas”). Value conflicts require us to make a decision or choice. We are responsible to recognize value conflicts for what they are and to resolve them using an ethical decision making process or, if we can’t resolve them, to refer them to someone who can help us. This document introduces one ethical decision making process for Providence Health System. A one-page outline of the process itself is attached. Any ethical decision making process is enhanced by education and experience, and thus we are encouraged to spend time reading and discussing this document before using it. We might also practice with sample cases before using it with actual cases. In any event, it is not meant to replace or supercede an ethical decision making process we might already be using at our facility. It is meant to clarify one way to make an ethical decision when confronted with a value conflict. Ethics is about Making Choices with Integrity …Providence Health System was built on a foundation of integrity. Mother Joseph and her companions brought a philosophy and a value-based way of living and serving to the West more than 140 year ago. That tradition lives on today in the more than [35,000] employees, physicians, board members, and volunteers who embrace the Providence mission and have made it their own. Every day each of us in the Providence System is called upon to perform a variety of tasks and undertake diverse responsibilities. The decisions we make and the duties we perform are critical to the furtherance of our organizational goals, the strengthening of our mission, and the living out of our core values…. Henry G. Walker President and Chief Executive Officer Providence Health System This quote is taken from the introduction to Providence Integrity: A Guide to Compliance and Ethics at Providence. In it, Hank Walker highlights the critical importance of making all of our decisions or choices with integrity. Making choices with integrity means that we make them in ways that consistently reflect the ethical standards imbedded in the 1 mission and core values of Providence Health System, as well as our own professional and personal values, the relevant legal and regulatory guidelines, and our organization’s policies. We focus on choices when we think about ethical decision making because choices give us the opportunity to affect the future and people in the future for better or worse. The future will be different after we make a choice, sometimes dramatically different, and that is why ethical decision making is so important. The following standard will be used throughout Providence Health System to assess our individual and collective competency in ethics. A Standard of Competency: The Four R’s of Ethics Providence Health System’s employees, physicians, board members and volunteers will make all choices with personal and professional integrity. If we are not sure what the right or best choice is in a given situation, our integrity requires us to: Recognize when a value conflict exists that requires an ethical decision making process; and Respond appropriately by: Resolving the value conflict in question by using an ethical decision making process, or Referring it in a timely manner and, if necessary, following up on the referral. Recognizing a Value Conflict: Types of Choices Choices require us to think ethically about the following three (3) categories: Conduct: Choices about what we do or how we act; Character: Choices about the kinds of people we are or want to become; Conditions: Choices about the kinds of organizational policies we seek to develop and the organizational culture we seek to foster; i.e., those factors that influence our conduct and characters, but don’t determine them. The vast majority of our ethical choices can be made simply by following the guidance provided by common ethical standards (i.e., personal and professional values, policies, or regulations). Such choices leave us with few doubts and little confusion. However, some 2 choices are difficult to make, and these choices may leave us wondering if we did the right thing. We must learn to recognize ethically difficult choices so that we and our organizations don’t “slide” into complex issues without being aware of them. There are a number of ethically difficult choices that come up again and again, and we should learn to recognize them. They all involve us in a conflict of values, forcing us to make a choice. Value conflicts that require an ethical decision making process arise when: 1) Decision makers are morally obligated to choose between two or more conflicting courses of action, and only one course of action can be chosen. E.g.: A clinician must choose between providing a medically indicated treatment (beneficence) and respecting the patient’s right to refuse it (autonomy). E.g.: A chief financial officer must decide between providing services locally and preserving 15 entry-level positions (compassion, respect) and contracting regionally for the same services and increasing the efficiency and quality of the work unit (stewardship, excellence). 2) Decision makers are obligated to choose between two or more courses of action that are governed by conflicting standards (e.g., ethical, legal, regulatory, religious, financial, or political) E.g.: Physicians must decide whether to seek a court order (legal) to override the explicit directions of Jehovah Witness parents (moral: parental autonomy; religious) not to give their minor child medically indicated blood products (medical). E.g.: A housekeeping employee finds a used, exposed needle in a patient’s room (safety, legal, professional). Before she decides whether to report it, she learns that it was left there by a normally very competent nurse who happens to be a good friend (loyalty); she also knows that the nurse’s marriage is breaking up (compassion). 3) Decision makers must choose between moral or other standards and “self-interest” (“self-interested” decisions are permitted unless they conflict with moral or other standards). E.g.: A clinician is trying to see as many patients as possible (stewardship, selfinterest), and is tempted to rush through the informed consent process (respect) with a patient who is asking an inordinate number of questions. E.g.: A senior operational leader is approached by a group of physicians with a very attractive joint venture opportunity (mission enhancement, self interest). On 3 investigating, she learns that the physicians want the medical center to bear a disproportionate share of the financial risk in return for an implied long term commitment of patient volume (legal). The implication to the operational leader is that she take the deal and make it work or the physicians will find a competing medical center that will. Losing this physician group will ensure that budget goals will not be met this year and, likely, in years to come. Responding Appropriately: Resolve or Refer the Value Conflict Follow an ethical decision making process to resolve value conflicts (attached) or refer them to someone who can help. We should use an ethical decision making process when we believe the decision makers are seeking to do the right thing and are not sure how. Resolving a value conflict means that we have discovered some satisfactory way to address the concerns represented by the conflicting values or that we have made a choice that represents the right or best choice, all things considered, in spite of the fact that some concerns may not be addressed to our complete satisfaction. We may refer value conflicts to the following people: Our local or regional mission leader, local or regional ethicist or ethics consultant, local or system Integrity Liaison Officer, or Jan C. Heller, Ph.D., System Director of the Office of Ethics and Theology, at 206-464-4728 or jan.heller@providence.org. Copyright 2000 by Providence Health System Ethical Decision Making for Leaders.doc 6/5/2000 4 An Ethical Decision-Making Process: Recognizing and Resolving Value Conflicts Step 1 Recognize the value conflict and decide whether to resolve or refer it. If resolving it… Analyze the Value Conflict Step 2 Identify all relevant decision-makers and facilitate their input (it is important to identify all decision makers so as not to bias the process). Depending on circumstances and your leadership role, you may be the only “relevant” decision maker. Consult the Operating Principles, Governance Matrix and Leadership and Decision Making Styles to determine relevant decision makers. Step 3 Decision makers should agree on the conflict to be resolved. Gather enough information to define the value conflict clearly. Consider the following… Facts: Factors: Step 4 What, who, when, how, why? Medical, social, economic/financial, political, legal, religious, etc. List the alternative choices that address the conflict, and for each… 4a Identify the relevant stakeholders (stakeholders are persons, organizations, or institutions affected by the choice). 4b Predict effects on stakeholders (this step may require extensive informationgathering; if confidentiality permits, discuss alternatives with affected stakeholders). Evaluate the Alternatives Step 5 Make the “right” or best decision by evaluating the effects of each alternative on the relevant stakeholders Effects will be positive, negative, or neutral in light of PHS Mission and Core Values, the PHS Operating Principles, and the wider Catholic moral tradition (e.g., official church teaching documents; Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services). Also consider other standards for evaluating effects (e.g., professional, personal, social, legal, financial, or political standards; also self-interest and feasibility). Loop back to previous steps, if necessary. Implementation and Follow-up Step 6 Communicate decision as required. Address unavoidable negative effects on affected stakeholders.