Resource - The Stewardship Network

advertisement

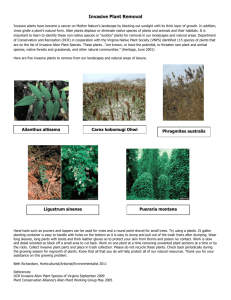

How Much Do You Know About Your Garden’s Interactions with Nature? Leslie Kuhn, Field Project Coordinator, Mid-Michigan Stewardship Initiative and Professor of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, Michigan State University A B Most of us garden because we like to grow our own healthy food and love to have nature around us. Yet our gardens can affect the natural areas surrounding our homes in some unexpected ways. Take the quiz below, and come up with your own answers. Then check out our answers at the end! Question 1. Biodiversity is one important measure of the health of our gardens and the surrounding natural areas. How can we measure biodiversity? Question 2. Can you count on the plants sold in nurseries to be good for your garden and safe for nature? Question 3. Really, what makes a plant invasive? Are the dandelions and clover in my lawn invasive? Question 4. Are non-native plants the only invasive species? C Question 5. What are the some of the benefits of planting Michigan native plants over non-native cultivars or hybrids? Question 6. Is it good to return yard waste to nature by composting it and then spreading the compost along woodland or wetland edges? Question 7. Does nature take care of itself if we leave it alone? D C Question 8. Can you tell native from invasive non-native plants? Check out the 17 photos on this page and the next. Which plants are good? Bad? Question 9. How can I help nature in my own area? See the next page for answers! E D C F G 1 H I J L K Answers 1. An intuitive measure of biodiversity is the number of different species inhabiting an area. A more elaborate but similar measure is the so-called Floristic Quality Index, which weighs the number of species observed by the rarity of habitat used by each species. In this measure, a dandelion (which grows in many different habitats, including the alps!) has a low weight, while a rare wetland orchid that grows only on sphagnum hummocks has a high weight. According to the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, it turns out there are just over 1,800 species of plants that are native to Michigan (meaning they were here at the time of European settlement), of which 31 are now endangered, 210 threatened, and 110 of special concern (rare and apparently decreasing in population). There are an additional 800 non-native plants that have established significant populations in the wild. 2. Nurseries in Michigan no longer sell plants that are declared noxious weeds by state law. An example of a former nursery plant that is now illegal to sell or move in Michigan is Japanese knotweed, which cracks cement and is very difficult to control; it cost $120 million just to remove this plant from the London Olympics sites! However, the bar is set high for declaring plants as noxious weeds in Michigan. There is a significant economic incentive to continue selling a number of plants that are pretty, even if they are known to be invasive. A couple of examples you may have in your own garden are Asian bush honeysuckles (any honeysuckle that is more than 3’ tall is likely to be one of these pests) and Japanese barberry, which is often sold in a variety with showy burgundycolored leaves. Both these plants are widespread invasives in our woods and other natural areas because birds and other wildlife eat the seeds and then drop them. Given that more than 200,000 non-native plant species have been introduced to the United States, it isn’t surprising that some of them are highly aggressive and become hard to control. It turns out that invasive species are second only to habitat loss as a threat to our natural areas. Unfortunately, it takes many years following the introduction of new plants to know whether or not they will become invasive. 3. Invasive plants are defined as those that spread into natural areas and not only survive but dominate the native plants. Thus, dandelions and clover aren’t considered invasive because they only spread rampantly in cultivated areas, not natural ones, whereas Asian honeysuckle, Japanese barberry, and Japanese knotweed are invasive. A combination of hyper-competitive features allows exotic plants to take over natural areas. Their native predators (the insects and animals that adapted to browse these plants in the original homeland) were not brought along with the plants M N N O 2 P O Q when they were imported. Many of these plants are also allelopathic (from the Greek, meaning “doing harm among others”), secreting substances that suppress nitrogen fixation or other needed functions of neighboring plants. Most invasive plants also seed profusely (common mullein produces up to 175,000 seeds per stalk!), and often their seeds are long-lived. Garlic mustard seeds last for at least 9 years, and mullein seeds are viable after 100 years! Invasive species typically leaf out earlier in the season and die back later, giving them a longer growing season and more time to crowd out natives. 4. Some native species can be invasive, too, due to disruption of the ecological network. For instance, white-tailed deer populations in southern Michigan have exploded due to suppression of their natural predators (wolves and cougars), and the deer now overbrowse the native forest understory as well as our gardens. Red maples have overtaken and shaded out many of the oak woodlands in the Lower Peninsula due to suppression of the natural wildfires that used to pass periodically across the land. Red maples are shade-tolerant but susceptible to fire, whereas oaks are fire resistant while requiring sunny, open areas to thrive. The need for sun is a trait shared by many native wildflowers, which are also shaded out in our fire-suppressed woods. 5. Our native plants have co-evolved with native butterflies, birds, bees, and browsing animals, and the animal world depends on an intact native plant community. For instance, birds, even the nectar-sippers like hummingbirds, gain necessary protein in their diet by feeding on insects and their larvae. While native insects depend on native plants for food, the same plants need birds to feed on the insects so they won’t be over-browsed. These plants and animals are exquisitely balanced in time and place in an intact ecosystem. A familiar example is the lovely monarch butterfly, which relies on milkweed plants as a larval food source and as a source of nectar for the butterfly. Conversion of natural areas to cornfields for biofuel development (about half the monarch territory in the U.S.) and suppression of milkweed growing in agricultural areas have contributed to a decimation of monarch populations in recent years. The total overwintering area occupied by monarchs in Mexico was under 2 acres in the winter of 2013, a 25-fold reduction relative to 1996. Insect-plant relationships are also synchronized. For instance, native bees depend on the earlyflowering willows in our wetlands as one of the only available food sources before spring really warms up, and later-flowering plants, even those attractive to bees, can’t fill the gap. So, planting and maintaining native plants on our own properties ensures the presence of food that our native insects and animals need for survival. They, in turn, contribute to pollinating our food crops, as well as giving us delight! Native plants are also surprisingly beautiful. The Xerces Society is encouraging our road commissions and transportation agencies to plant native wildflowers including milkweed along the roadsides, which can make a giant difference, given the 120,000 miles of paved roads in Michigan! 6. Yes and no! It is great to break down your yard waste, but that waste often includes weed seeds. Composting (especially in a well-run yard waste facility with composters) is hot enough to break down many seeds, but not the toughest invasive plant seeds (for instance, the hard-capsuled seeds of plants in the mustard family). Garlic mustard and dame’s rocket have spread for acres around our local yard waste station because of this. Also, native plants are well-adapted to the soil in which they grow, and spreading compost or commercial fertilizer around them (especially in or near wetlands) creates an excess of nutrients that create a bloom of bacteria, algae, and fungi. The overgrowth of these microbes disturbs the native residents (including salamanders, frogs, fish, and turtles) and drives wetlands towards a stagnant, unhealthy state. When we think of smelly swamps, it is due to disturbance, not natural processes, since healthy wetlands purify our water. So, it is best to keep your compost in a composting bin that gets good and hot, and then just use well-composted material in the landscaped rather than native parts of your garden. Most colonies of invasive species in natural areas start either from people well-meaningly deposting their yard waste along the 3 edge, or from construction-related disturbance (including equipment contaminated with invasive roots and seeds). 7. Not when nature is close to developed areas. There are still some places where nature is relatively untouched by humans – such as remote Alaska and the Crown of the Continent in the Rockies – but there are unfortunately not many places like that in Michigan. Every edge of a natural area is exposed to human activities, from mowing, drainage, and road-building to the invasive species that thrive in disturbed areas, to the effects of global climate change and pollution. The main problem in conserving our natural areas is that there are not enough nature-knowledgeable people available to take care of them. For instance, the DNR Parks system, with tens of thousands of acres of natural areas, recently only had four full-time staff members devoted to their stewardship. Most park systems in Michigan have no personnel trained to identify and remove invasive species or monitor the native species. Without active monitoring and intervention, invasive species eventually take over. But there are lots of interesting and healthy things you can do to help. See question 9! 8. Non-native invasive species: A. Ground ivy (Glechoma hederacea) – A common, vine-forming lawn weed that can spread explosively when cuttings find their way into natural areas. C. Common reed (Phragmites australis) – An aggressive 8-12’ tall invader, typically in wetlands. Its Greek name means “wall”, and this plant forms a dense, moving wall that consumes native habitat. D. Autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) – An import from eastern Asia, planted in the mid-1900’s to provide forage for deer, this is one of the most pervasive woody invasive shrubs in our woodlands and roadsides. Identifiable by small white-spotted scarlet-colored olive-shaped fruits in the fall, plus the silvery undersides of its wavy-edged leaves. E. Asian bush honeysuckle (Lonicera spp.) – Large shrubs with sweet-smelling spring or summer flowers in white, yellow, orange, or pink. Mature stems are hollow. Also ubiquitously invasive. G. Dame’s rocket (Hesperis matronalis) – A European mustard with purple (aging to white) fourpetaled flowers that bloom in May and June. Native phloxes look similar but have five petals. See the note on how to dispose of this and other invasive mustards under garlic mustard, below. H. Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica) – A red streaked bamboo-like reed that evolved to grow on lava, it can crack through building foundations and roads. Japanese knotweed spreads aggressively when mowed or trimmed, and cut stalks start new plants. It must be controlled with specialty herbicides (such as Milestone® on uplands or Habitat® in wetlands). I. Garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) – This is the most common and problematic invasive herb in Michigan due to its profuse, long-lasting seeds, allelopathic suppression of surrounding native plants, and roadside spread by mowing. To control it, dispose of plants before they release seed, in sealed bags in the trash/landfill (not yard waste), under Michigan Compiled Law, Section 324.11521. J. Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii) – An invasive shrub that spreads in woodlands and wetland edges. Still widely sold in nurseries, with purple or dark green leaves, thorny, zigzag stems, and bar-shaped bright red berries. (Photo by Lazaregagnidze, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.) N. Cutleaf teasel (Dipsacus laciniatus) – Very similar to Fuller’s teasel, which has purple flowers, this plant leaves persistent stalks with spiky seedheads after releasing its seeds. It spreads rapidly along the roadsides due to mowing. Use of the dried seedhead in flower arrangements at gravesides has also hastened its spread in the wild. P. Glossy buckthorn (Frangula alnus) – Native to Eurasia and Africa, this hedge-forming shrub forms inpenetrable, tall thickets in wetlands and can also grow aggressively on uplands. Distinctive features are the 8-9 pairs of prominent veins on the leaves and dense growth of vertical stems. 4 Q. Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense) – Despite the name, this plant is not North American. It quickly invades disturbed areas by forming large, perennial colonies linked by underground roots, and then releases masses of airborne seeds (as shown in this photo; the thistle flowers are purple). It can be readily controlled with Milestone® but is resistant to more common herbicides. Michigan native flowers: B. Butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa) – Not at all a weed, this is a sought-after, colorful native of well-drained, sunny spots, and a prime host for butterflies. F. Blue flag iris (Iris virginica) – A native that grows in both wet and well-drained areas. A robust, deer-resistant garden plant. However, the non-native yellow flag iris is a wetland invasive! K. Virginia bluebells (Mertensia virginica) – A lovely native spring ephemeral that grows happily in gardens and is uncommon in the wild in Michigan. L. Wood poppy (Stylophorum diphyllum) – Another native wildflower that is robust and versatile in home gardens. This one blooms for months on end. M. Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) – A surprising spring ephemeral with unusual leaves and bright white flowers. Folds up like an umbrella each evening! O. Bogbean or buckbean (Menyanthes trifoliata) – A delicate and fleeting emergent wetland flower. (Photos courtesy of Mid-Michigan Stewardship Initiative unless otherwise noted.) 9. Things you can do to support nature in your garden and its surroundings: Learn to identify native plants and invasive species and understand their interconnections with native insects and animals. A short list of good books: Newcomb’s Wildflower Guide, by Lawrence Newcomb and Gordon Morrison, Little/Brown Wildflowers of Wisconsin and the Great Lakes Region, by Merel R. Black and Emmet J. Judziewicz, University of Wisconsin Press Michigan Trees, by Burton V. Barnes and Warren H. Wagner, Jr., University of Michigan Press Bringing Nature Home: How You Can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants, by Douglas Tallamy, Timber Press Invasive Plants of the Upper Midwest, by Elizabeth J. Czarapata, University of Wisconsin A Field Identification Guide to Invasive Plants in Michigan’s Natural Communities, by Phyllis Higman and Suzan Campbell, Michigan Natural Features Inventory/MSU Extension (available as a downloadable pdf or as a book from http://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/invasive-species/fieldguide.cfm) A Field Guide to Invasive Plants of Aquatic and Wetland Habitats for Michigan, by Suzan Campbell, Phyllis Higman, Brad Slaughter and Ed Schools, Michigan Natural Features Inventory/MSU Extension (available as a downloadable pdf or as a book from http://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/invasive-species/AquaticsFieldGuide.pdf) Weeds of Canada and the Northern United States, by France Royer and Richard Dickinson, Lone Pine Publishing Web resources: http://www.michiganinvasives.org/resources/ (invasive species fact sheets and tutorials) 5 http://www.michiganinvasives.org/howto/#Control (controlling invasive species) http://michiganflora.net and http://wisflora.herbarium.wisc.edu (identifying native plants) Participate in workshops and become a member of these groups: Michigan Botanical Club (http://michbotclub.org) Wild Ones (native plant society; http://wildones.org) Wildflower Association of Michigan (http://www.wildflowersmich.org) The Stewardship Network (http://www.stewardshipnetwork.org) Michigan Conservation Districts (http://macd.org/local-districts.html) Add native plants to your landscape Good references: Landscaping with Native Plants of Michigan, Lynn M. Steiner, Voyageur Press The Living Landscape, Rick Darke and Doug Tallamy, Timber Press Native Alternatives to Invasive Plants, C. Colston Burrell, Brooklyn Botanic Garden Press Sources of native plants and seeds in Michigan: Michigan Native Plant Producers Association (http://www.mnppa.org/members.html) Milkweed for butterfly and bee conservation (http://www.monarchwatch.org) Control invasive species in your neighborhood, and volunteer to help in parks and natural areas The training resources listed above will help you become familiar with invasive plants Most neighbors want to understand what is good on their property versus what threatens it. Invasive species, if left unchecked, also degrade property values and appearance. You can volunteer during invasive species control workdays of the Stewardship Network, Michigan DNR Parks, The Nature Conservancy, Michigan Nature Association, Michigan Conservation Districts, Michigan Audubon Club, and your city and county parks and local nature centers. They provide valuable training that will help you control invasive species on your own land plus a social network of like-minded community members. 6