ATUL GAWANDE in conversation with PAUL HOLDENGRÄBER

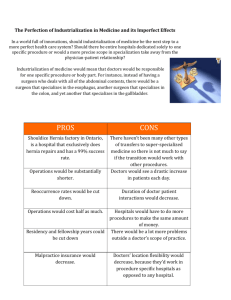

advertisement