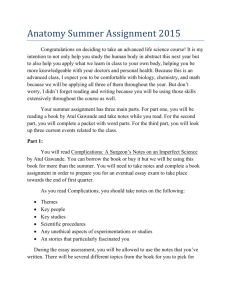

Surgical Checklist Profiled in Harvard Business Review (HBR)

advertisement

Surgical Checklist Profiled in Harvard Business Review (HBR) http://hbr.org/2010/04/health-care-needs-a-new-kind-of-hero/ar/1 Health Care Needs a New Kind of Hero An Interview with Atul Gawande by Gardiner Morse In his latest book, The Checklist Manifesto, surgeon and writer Atul Gawande describes how asking some simple questions before surgery starts—such as “Did we give the patient her antibiotic?” and even “Did we introduce ourselves to one another?”—can reduce infections and deaths by more than a third. Easy as this exercise is, it’s often met with hostility, because it challenges doctors’ cherished notions about status, autonomy, and expertise. In this edited interview, HBR senior editor Gardiner Morse asks Gawande what checklists reveal about the culture of medicine and how its dysfunctions might be fixed. HBR: Despite doctors’ resistance to new ideas, surgical checklists are gaining a foothold. What does that tell us about how to speed up other changes in health care? Atul Gawande: If you try to impose a new practice by simply telling the front line “Do this,” it will fail. That’s particularly true for something like a checklist, which many surgeons at first felt was beneath them. To get people to embrace a practice, it has to be easy and quick to use, adaptable to a variety of settings, and of obvious benefit. In hospital after hospital, checklists reduced mistakes and saved lives, and clinicians who used them saw greater efficiency and teamwork, which made them willing to continue using them. My operating room finishes up earlier in the day than others, which is one reason people like our checklists. The other crucial thing is having senior people who practice what they preach. When we piloted checklists in hospitals around the world, we asked the chiefs of surgery, anesthesiology, and nursing to be the first people to use them. Health care is moving toward teams, but that collides with the image of the all-knowing, heroic lone healer. That’s right. We’ve celebrated cowboys, but what we need is more pit crews. There’s still a lot of silo mentality in health care—the mentality of “That’s not my problem; someone else will take care of it”—and that’s very dangerous. How do we move toward a culture where effective teams are the norm? Part of the answer is a change in medical training. Most medicine is delivered by teams of people, with the physician, in theory, the team captain. Yet we don’t train physicians how to lead teams or be team members. This should begin in medical school. One of the most fascinating experiments along these lines is at the University of Nevada at Reno, where the schools of medicine and nursing have combined facilities and courses. Doctors and nurses in training are learning how to work together. It’s a brand-new thing. But simply training people in team techniques isn’t enough, is it? To get effective collaboration, don’t you have to change doctors’ self-image? To continue reading, subscribe now or purchase a single copy PDF. Already an online or premium subscriber? Sign in or register now to activate your subscription.