Sheffield Fairness Commission

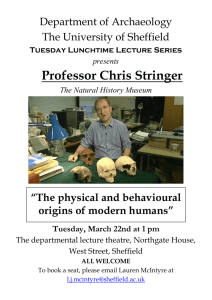

advertisement

Sheffield Fairness Commission Call for Evidence - Sheffield Hallam University Sheffield Hallam University is pleased to submit evidence to the Commission. It is largely based on the University's Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research (CRESR) extensive knowledge and experience in the field. 1. What specific evidence do you hold about inequalities and fairness that may be of use to the Commission? Approximately 50,000 of Sheffield's working age residents (13.1%) were claiming out of work benefits in August 2011. This was higher than the national rate of 12.3%, but on a par with Yorkshire and Humberside. Nearly half are claiming Employment and Support Allowance, Incapacity Benefit or Severe Disablement Allowance. The distribution of IB/ESA claimants varies widely across the city with more than one in ten working age residents on these benefits in Norton, Nether Shire, Burngreave, Park, Firth Park, Southey Green and Manor. The Manor has the highest rate with 14.1% of working age residents on IB/ESA. In contrast, fewer than 3 people in 100 were claiming these benefits in Broomhill, Ecclesall and Hallam. Sheffield Hallam University's Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research has undertaken substantial work in the field of worklessness and regeneration that explores the causes of, and potential remedies, to social and spatial inequalities. We have pioneered non-standard labour market measures as a means of strengthening our understanding of labour market processes and problems of labour market detachment. The best known are the reports providing estimates of 'real unemployment' for all local authority districts in Great Britain (Beatty et al, 2007). This has highlighted a tendency for those who are out of work to shift away from active job search towards economic inactivity and detachment from the labour market. Fletcher has carried out a stream of research since the mid-1990s that has explored how deprived communities (including the Manor estate and Shiregreen) and groups (white working-class, offenders etc.) have been adversely affected by economic transformation. A common policy assumption is that helping workless individuals access paid work can help reduce social and economic inequalities. However, research undertaken by CRESR showed paid work is not always a route out of poverty. A study for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) on 'Work and Worklessness in Deprived Neighbourhoods' found many residents were trapped in ‘poor work’, characterised by combinations of low pay, long hours or pervasive job insecurity (Crisp et al., 2009). At the same time, the research found that low-paid, low-skilled work can provide important social benefits such as a sense of purpose, social contact and a valued sense of identity Crisp, 2010). These findings suggest that paid work often plays a highly ambiguous role in supporting individuals and their families. One implication for Sheffield City Council is that local initiatives to tackle worklessness need to be ensure that they consider job quality. 1|Page 2. Based on your evidence what is your or your organisation’s analysis of the cause/s of inequalities within Sheffield? The UK has entered a new phase of capital accumulation which is marked by intensified processes of economic globalisation, capital and labour mobility and welfare restructuring. Economic restructuring has polarised labour markets between 'knowledge and information intensive' and 'labour intense and low productivity' sectors. In terms of the latter, there is a rise in low paid work, in part-time and flexible employment (voluntary and involuntary) and in the growth of the informal economy. Consequently, the opportunities available to those with few skills are insecure, poorly paid and do not offer a route of poverty. Labour market de-regulation has further exacerbated these trends. Fletcher has published many articles that have explored the impact of economic transformation on deprived communities (including the Manor estate and Shiregreen) and the working class. Wage inequality has risen significantly since the late 1970s. At the national level skilled workers have improved their position relative to less skilled workers and there has been a 'hollowing out' of middle paying jobs. In terms of the latter, there has been very rapid growth in the top two deciles of job quality (as measured by mean occupational wages from 1979 to 2008) and positive growth in the bottom deciles but declines in between. It has also become harder to rise through the wage distribution over time. The introduction of new technologies which require more skilled workers to operate them has been identified as another factor. 'Area effects' are an insignificant part of the explanation. However, research conducted by Fletcher et al (2008) on the Manor estate has found that residents reported that there was something about the area that made it more difficult for them to get work. The main issues reported included: experience of 'postcode discrimination' by prospective employers; social norms and routines that can result in lifestyles or peer influences resistant to formal paid work; the narrow spatial horizons of some residents which serve to restrict the geographical extent of job search and travel to work. The economic divide in Sheffield may have been further exacerbated by the inability of affluent households to migrate outwards into the rural hinterland due to restrictive planning policies (National Park and Green Belt). This has meant that many have settled for living in the city's western suburbs. This is likely to have driven up house prices in these areas even further, and has helped to contribute to the Hallam constituency being one of the most affluent in the country. 2|Page 3. Are there any examples of good practice in relation to reducing inequalities and increasing fairness (from within the city, elsewhere in the UK, or overseas) that the Commission should be aware of? Sheffield Hallam University's Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research undertook an evaluation of a small-scale Intermediate Labour Market (ILM) project delivered by Blackpool City Council in 2009. This provided long-term, workless individuals with opportunities to undertake a paid work placement in the public or third sector. The authors found this approach was highly effective in supporting individuals facing multiple barriers to gain valuable work experience and, in some cases, to secure permanent, reasonably-paid work in those sectors. Sheffield City Council may well want to consider the potential for implementing a similar scheme to support more marginalised individuals living in high areas of worklessness. At the same time, it is important to remember that small-scale, local interventions may have a transformative effect for individuals but less impact across the wider area. Research undertaken for CLG on the effectiveness of the New Deal for Communities (NDC) Programme (see CLG, 2009a, 2000b) found neighbourhood-based projects to tackle worklessness made little difference to overall levels of worklessness in NDC areas. They were particularly effective, for example, in supporting young BME groups. Localised interventions can, therefore, deliver fairness to individuals but this may not translate into significant reductions in worklessness. The evaluation of the South Yorkshire Social Infrastructure Programme (SYSIP) undertaken by the Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research (Wells et al. 2010) showed that the programme had a relatively modest impact on combatting social exclusion in South Yorkshire, with quite considerable variation in the impacts across the programme. It found relative success of volunteer programmes in supporting some groups in long term unemployment and on sickness related benefits. However, the benefits returns were of a relatively small scale and required long term support. Similarly, it found that capital investments in voluntary and community sector support and development organisations (a district and neighbourhood levels) has helped coordinate actions by frontline organisations. However, the evaluation also raised concerns that 'Community Action Programmes' targeted at developing the role of sustainability of 'neighbourhood infrastructure' were largely ineffective set against the scale of social and economic deprivation these organisations were seeking to address. The evaluation also found that whilst infrastructure support was reaching a high proportion of frontline third sector organisations, the support could have been better targeted at organisations making a greater contribution to addressing inequality (an overall objective of SYSIP) and those organisations which were at greatest risk of collapse. 3|Page The following information is presented to illustrate how the University promotes and supports aspiration, progression and participation in Higher education, in the context of the Commission's work in tackling inequalities and promoting fairness. Outreach and UK Recruitment Development The University's Outreach and UK Recruitment Development team work closely with a network of 100+ institutions within a 50 mile radius of the City, including 13 in Sheffield to raise attainment and aspirations to Higher Education. raise the awareness and opportunities of higher education for local learners. inspire, using student ambassadors as positive role models, and showcasing exciting opportunities and career pathways which HE can offer Initiatives that tackle issues around access and disadvantage for particular groups of learners in Sheffield include: Looked After Children (LAC) We work closely with our Local Authority partners to produce high quality raising aspirations events for young people in care from Y9 to Y11. This work is carried out in partnership with The University of Sheffield. We currently have 41 LAC/care leavers enrolled at the University. During 2010/11, 48 Looked After Children attended visits to the University and 100 attendees (mainly teachers and advisers) attended our transition conference. The package of support for LAC includes A non repayable bursary of £1,500 per year of study Dedicated support from our Care Leaver Co-ordinator Support in securing suitable accommodation (including 365 accommodation) Priority access to a personalised finance and welfare advisory appointment with the Students’ Union Compact The Compact scheme supports students who have the potential to study at University but face certain barriers to doing so, including those students who can only have Sheffield Hallam University as an option for them. The scheme is available to all students at Sheffield schools and colleges and applicants are automatically included within the Compact. During 2010/11 a total of 341 students (266 or 78% from Sheffield) were accepted onto the scheme, with 154 (110 or 71% from Sheffield) progressing to enrolment. 4|Page Mentoring Our undergraduate student mentors deliver a series of interactive and engaging themed group sessions to Year 10 students in local schools in South Yorkshire, discussing topics such as introductions to Higher Education, GCSE choices, study skills, financial awareness and future choices. The scheme is targeted at students from Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) groups under-represented in HE, with the aim to: raise aspirations improve attitudes towards higher education improve motivation and self-esteem. During 2012/13 we have 19 trained current student mentors who are working with 46 students from 4 local schools (34 are based in 3 Sheffield schools). Financial support for Sheffield students The University has a range of bursary schemes to support local students as they enter and progress through their studies. A measure of relative inequality can be seen in the profile of bursary support the University provides to its students, based on residual household income. Data from the Student Loans Company in 2010-11 shows that 2125 University students with a Sheffield postcode were assessed as having an income of less than £20,000, representing 62% of all Sheffield postcode students. 4. What do you or your organisation believe would be the best way to tackle inequalities and increase fairness in the city? 5. What should be the top 3 priorities for the city? There are few simple panaceas which could significantly address inequalities in Sheffield. The experience of the last 30 years is that whilst there is scope for considerable action at a city level, some policy and economic levers are outside the gift of local policy makers. Any priorities also need to be set against what are likely to key economic, social and environmental challenges for the city in the future. Employment and Economy. The research evidence points to a need to address fundamental weaknesses in the demand side of the economy and the challenges of not simply generating jobs, but high quality jobs. Facilitating the growth of jobs that pay a 'living wage' and provide a stepping stone to better quality work should be an important priority and cuts across policy and sectoral domains. Following this, improving the human capital of deprived groups to facilitate access to better quality work. Community. Supporting and protecting communities in the context of the economic downturn and public sector retrenchment. In the context of a shrinking public sector, this will demand the coordination of service 5|Page delivery to minimise duplication and maximise efficiencies and the targeting of increasingly limited resources through specific interventions to promote resilience. Moving forward with this agenda will demand understanding of the factors underpinning community resilience and how to recognise and respond to deficits in these factors within particular communities. The withdrawal of state activities will make the understanding of resilience increasingly important if the future if inequalities are not to rise further. 6|Page Annex Beatty. C. and Fothergill, S. (2011) Incapacity Benefit Reform: the local, regional and national impact. Sheffield: CRESR. http://www.shu.ac.uk/_assets/pdf/cresr-final-incapacity-benefit-reform.pdf Beatty, C., Fothergill, S., Gore., T. and Powell, R. (2010) Tackling worklessness in Britain's weaker local economies. Sheffield: CRESR. http://www.shu.ac.uk/_assets/pdf/cresr-tackle-worklessness-report-nov10.pdf Beatty, C., Fothergill, S., Houston, D. and Powell, R. (2010) 'Bringing Incapacity Benefit numbers down: to what extent do women need a different approach?' Policy Studies 31 (2), pp. 143-162. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/01442870903429603 Beatty, C., Fothergill, S., Gore, T., and Powell, R. (2007) The Real Level of Unemployment 2007. Sheffield: CRESR. http://www.shu.ac.uk/_assets/pdf/cresr-RealLevelUnemployment07.pdf Beatty. C. and Fothergill, S. (2005) 'The diversion from 'unemployment' to 'sickness' across British regions and districts'. Regional Studies, 39 (7), pp. 837-854. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00343400500289804 Crisp, R., Beatty, B., Lawless, P., Foden, M. and Wilson, I. (2009) Understanding and tackling worklessness: Lessons and policy implications. Evidence from the New Deal for Communities Programme. London: CLG. http://www.shu.ac.uk/_assets/pdf/cresr-understanding-tacklingworklessness.pdf Crisp, R., Fothergill., S., Gore, T., and Platts-Fowler, D. (2009) Sheffield Worklessness Study: The characteristics and aspirations and skill needs of Incapacity Benefit claimants and lone parents on benefit. Sheffield: CRESR. Crisp, R. and Fletcher, D. (2008) A comparative review of workfare programmes in the Unites States, Canada and Australia. London: Department for Work and Pensions. Research Report No. 533. http://research.dwp.gov.uk/asd/asd5/rports2007-2008/rrep533.pdf Fletcher, D. (2011) 'Welfare Reform, Jobcentre Plus and the Street-Level Bureaucracy: Towards Inconsistent and Discriminatory Welfare for Severely Disadvantaged Groups?' Social Policy and Society, 10 (4), pp. 445-458. http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayFulltext?type=6&fid=8350198&jid= SPS&volumeId=10&issueId=04&aid=8350197&fulltextType=RA&fileId=S1474 746411000200 Fletcher, D.R. et al (2011) Qualitative study of offender employment review: final report. London: Department for Work & Pensions. DWP Research Report No. 784. http://research.dwp.gov.uk/asd/asd5/rports2011-2012/rrep784.pdf 7|Page Fletcher, D.R. et al (2009) Qualitative evaluation of the Jobseeker Mandatory Activity (JMA). London: Department for Work and Pensions. Research Report No 553. http://research.dwp.gov.uk/asd/asd5/summ2009-2010/553summ.pdf Fletcher, D.R. et al (2008) Social housing and worklessness: Qualitative research findings. London: Department for Work and Pensions. Research Report No. 521. http://research.dwp.gov.uk/asd/asd5/rports20072008/rrep521.pdf Fletcher, D.R. et al (2007) Evaluation of the Working Neighbourhoods Pilot: Final Report. London: Department for Work and Pensions. Research Report No. 411. http://research.dwp.gov.uk/asd/asd5/rports2007-2008/rrep411.pdf Fletcher, D.R. (2007) 'A culture of worklessness? Historical insights from the Manor and Park area of Sheffield'. Policy and Politics, 35 (1), pp. 65-85. http://docserver.ingentaconnect.com/deliver/connect/tpp/03055736/v35n1/s4. pdf?expires=1332860578&id=67976185&titleid=777&accname=Sheffield+Hall am+University&checksum=A66DAD4514E74EDEBF17E4ADC14CE826 Fletcher, D.R. (2010) 'The workless Class? Economic Transformation, Informal Work and Male Working Class Identity'. Social Policy & Society, 9 (3), pp. 325-336. http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=77 88179 Fletcher, D. R. (2009) 'Social Tenants, Attachment to Place and Work in the Post-industrial Labour Market: Underlining the Limits of Housing-based Explanations of Labour Immobility?' Housing Studies 24 (6), pp. 775-791. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/02673030903205895 Fletcher, D.R. (2008) 'Offenders in the post-industrial labour market: from the underclass to the undercaste?' Policy and Politics, 36 (2), pp. 283-297. http://docserver.ingentaconnect.com/deliver/connect/tpp/03055736/v36n2/s8. pdf?expires=1332860704&id=67976226&titleid=777&accname=Sheffield+Hall am+University&checksum=02A27A131A844BD4F698991898CCFE8B Fletcher, D.R. (2008) Employment and Disconnection: Cultures of worklessness in Neighbourhoods in Flint, J. and Robinson, D. (Eds) Community Cohesion in Crisis? New dimensions of diversity and difference. Bristol: Policy Press. Green, A and Adam, D. (2011) City Strategy: Final Evaluation. London: Department for Work and Pensions. Research Report No. 783. http://research.dwp.gov.uk/asd/asd5/rports2011-2012/rrep783.pdf Wells, P. et al (2010) Evaluation of the South Yorkshire Social Infrastructure Programme: Summary Report. Sheffield: CRESR. http://www.shu.ac.uk/_assets/pdf/cresr_A_SYSIP_summary_report.pdf 8|Page