Verbal communication without propositional and

advertisement

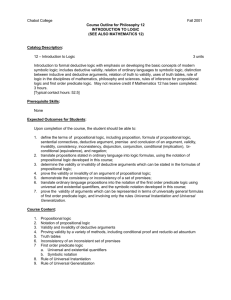

Verbal communication without propositional and logical form? © Ernst-August Gutt, 26/05/2004 DRAFT - Comments welcome! (Excerpt from E.-A. Gutt, Representation, metarepresentation and interpretation in relevance theory, unpublished ms, 20/08/2002) Propositional form It seems Sperber and Wilson use the term propositional form in two different ways: in the abstract, philosophical sense and in a cognitive, psychological sense. Propositional form in the abstract sense In the abstract sense, propositional form is characterised as a logical form which was itself characterised as an abstraction from a mental representation - “which is semantically complete and therefore capable of being true or false” (Sperber and Wilson 1986/1995:72). Both utterances and thoughts are said “have” propositional forms, one can talk about the “propositional form of a thought” (Wilson and Sperber 1988:135) as well as about the “propositional form of an utterance”. In this abstract use of the term ‘propositional form’, … “… the relation between an utterance and the state of affairs it describes is analysable into three sub-relations: between an utterance and its linguistically encoded logical form, between the logical form of an utterance and its fully propositional form, and between the propositional form of an utterance and the state of affairs it describes.” (Wilson and Sperber 1988:134) These relationships may be diagrammed as follows, including the names of the academic disciplines that deals with each, as stated by Wilson and Sperber: utterance logical form linguistic semantics D:\533566388.doc propositional form pragmatics 2/16/2016 state of affairs semantics of mental representation 1/6 Propositional form as cognitive concept? On the other hand, Wilson and Sperber seem to treat propositional form as a psychological notion, characterising it as “an intermediate level of representation between utterances and the states of affairs they describe” (Wilson and Sperber 1988:134). It is meant to help explain how the speakerintended meaning enters into the process of comprehension, given that a given utterance can be used to refer to a multitude of states of affairs, but for communication it is important that the hearer is able to pick out the state of affairs intended by the speaker. This seems to be confirmed by a number of statements: “The propositional form of an utterance is obtained by selecting a linguistically encoded logical form, completing it … to the point where it represents a determinate state of affairs, and … enriching it in various ways.” (Wilson and Sperber 1988:134). “It is [fully propositional forms] that constitute the individual’s encyclopaedic knowledge, his overall representation of the world.” (Sperber and Wilson 1986/1995:73). Problems with ‘propositional form’ One problem with the term propositional form, then, is that it is used in two different senses, without this distinction necessarily marked. This is a potential source of confusion, if it both true to say that ‘propositional form is a level of mental representation’, and, on the other hand, that ‘mental representations can have propositional forms’. This may be just a matter of terminological inconsistency that could be fixed without too much difficulty. However, there appears to be a more serious problem with this notion. Thus Wilson and Sperber state that “utterances do not always represent a thought with the identical propositional form: in loose talk and metaphor, the propositional forms of thought and utterance merely resemble each other to a certain degree” (Wilson and Sperber 1988:135). Thus, it appears we now get a much more complex picture of verbal communication: utterance thought logical form propositional form ? propositional form state of affairs state of affairs D:\533566388.doc 2/16/2016 2/6 The main puzzle here is the following: though the propositional form of an utterance was said to pick out the state of affairs which the utterance was intended to represent - in distinction from all the ones it could be used to represent - it is now claimed that “an utterance does not always represent a thought with the identical propositional form” - which seems to say that the propositional form of an utterance can be different from the propositional form of the thought which the utterance is intended to represent. This raises the question: if the ‘propositional form of an utterance’ is not what the speaker intended to represent after all - then what is it? Note that the problem raised here is not that the relationship between an utterance and a thought can be a ‘loose’ one, in some sense; rather, the problem is what is meant by ‘the propositional form of an utterance’ when utterance are used in this loose sense? As far as I am aware, this question is not discussed or answered. Toward a solution One possible way of avoiding this problem would be to try to account for communication processes without reference to the abstract terms of ‘logical form’ and ‘propositional form’. How could this work? Utterances, like any other stimuli, are used in ostensive communication to provide evidence of thoughts which the communicator intends others to infer. One of the tasks of comprehension is to construct (or pick out) the right, that is, communicator-intended, assumptions constituting the intended body of thought. Like other stimuli, utterances have all sorts of properties: acoustic, linguistic (structural, procedural) representational, etc. Like always, the audience has to found out - guided by the relevance-theoretic comprehension procedure which of these properties are intended to give ‘clues’ toward the intended interpretation. What is unique about utterances as verbal stimuli, are its linguistic properties, which we might properties that are processed by a special module of the mind, the linguistic module. It is the linguistic properties that give verbal utterances their special status in communication: “Linguistic communication is the strongest possible form of communication: it introduces an element of explicitness where non-verbal communication can never be more than implicit. Of the assumptions conveyed by an utterance, at least those that are explicitly conveyed can be enumerated.” (Sperber and Wilson 1986/1995:175). A long-standing idea has been that the special property that enables utterances to do this is their ‘logical form’ (‘semantic representation’), which is an ‘incomplete assumption schema’ or ‘blueprint for a propositional form’. Generative linguistics has standardly assumed that the output of the linguistic D:\533566388.doc 2/16/2016 3/6 module are logical forms (‘semantic representations’), and Sperber and Wilson have built on this idea: If sentences do not encode thoughts, what do they encode? What are the meanings of sentences? Sentence meanings are sets of semantic representations, as many semantic representations as there are ways in which the sentence is ambiguous. Semantic representations are incomplete logical forms, i.e. at best fragmentary representations of thoughts. (Sperber and Wilson 1986/1995:193) The coded communication is of course linguistic: acoustic (or graphic) signals are used to communicate semantic representations. The semantic representations recovered by decoding are useful only as a source of hypotheses and evidence for the second communication process, the inferential one. (Sperber and Wilson 1986/1995:176) But this is not a necessary assumption. Linguistic stimuli could facilitate the process of utterance interpretation without encoding anything like a ‘logical form’. All that is necessary is that the output of the linguistic module facilitates the construction of the intended assumption. This output could consist in a number of rather abstract ‘clues’ that serves as input to and guide the inferential processes, but that themselves never amount to anything like a representation or assumption schema. But do we not have the notion of ‘sentence meaning’ as opposed to ‘utterance meaning’? If sentences don’t have logical forms, then how do we account for this notion of sentence meaning? First of all we need to note that, even if we follow Sperber and Wilson in assuming an encoded ‘logical form’ or ‘semantic representation’, this does not in itself explain intuitions of ‘sentence meaning ‘ because “One entertains thoughts; one does not entertain semantic representations of sentences. Semantic representations of sentences are mental objects that never surface to consciousness” (Sperber and Wilson 1986/1995:193). If ‘semantic representations’ are not accessible to consciousness, then they can hardly be said to account for our intuitions of ‘sentence meaning’. Thus, the account with encoded logical form does no better in explaining our intuition about ‘sentence meaning’ than an account without logical form. How then can one explain the idea of ‘sentence meaning’? I think it can be explained by the automatic operation of the relevance-theoretic comprehension procedure: when we are given ‘a sentence’ in isolation, without any clue to particular contextual assumptions or a particular communicative intention, then we still follow the urge to interpret - but naturally using only very general contextual assumptions. This would seem to agree with Sperber’s observation that human beings are bent on D:\533566388.doc 2/16/2016 4/6 interpretation, bent on attributing intentions, including informative intentions, to others (cf. Sperber and Wilson 1986/1995:23-24; Sperber 1994). It seems to me that Sperber and Wilson’s intuition that even ‘loosely’ used utterances have a ‘propositional form’ that is different from the actually intended interpretation can be explained along similar lines. We may have assumptions available - other than the intended ones - that would lead to a different interpretation of the utterance, and this makes it possible to think of ‘a literal’ interpretation of a metaphorical utterance, for example. Note, however, that this does not seem to be a necessary condition: in many cases of metaphorical or loose use, we may not even be aware of any other, literal interpretation. If this is correct, then our account of utterance interpretation is greatly simplified: by cutting out reference to the abstract terms ‘logical form’ and ‘propositional form’, two levels of intermediate representation are no longer needed. What we are left with are a) the verbal stimulus (utterance), b) the mental representation that is (intended to be) inferred from it, c) the state of affairs to which it refers The verbal stimulus (utterance) needs to be perceived and then its interpretational properties are assessed; this includes both coded and noncoded properties. (See papers by Gutt on identifying communicative clues.) Some of the properties that guide the process of constructing a mental representation are decoded. This is done by the linguistic module, presumably an input module of the mind. The properties coming out of this module can be representational, invoking concepts, and/or computational, directing interpretational procedures. In addition, utterances can have properties that do not require the linguistic module in particular - such as loudness, clarity, voice quality (clear, husky, etc.) and so forth. Guided by the relevance-theoretic comprehension procedure, the mind utilises any of these ‘clues’ that seem promising, and, if successful, infers the intended body of thought, entertained by the hearer as a mental representation. References Sperber, D. 1994 'Understanding verbal understanding'. In J. Khalfa (ed) What is intelligence? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 179-198. Sperber D. and D. Wilson 1986/1995 Relevance: communication and cognition. Oxford: Blackwell. Wilson and D. Sperber 1988 'Representation and relevance'. In Ruth M. Kempson, Mental representations: The interface between language and reality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 133-153. D:\533566388.doc 2/16/2016 5/6 D:\533566388.doc 2/16/2016 6/6