Giles of Rome (c1247-1316)

advertisement

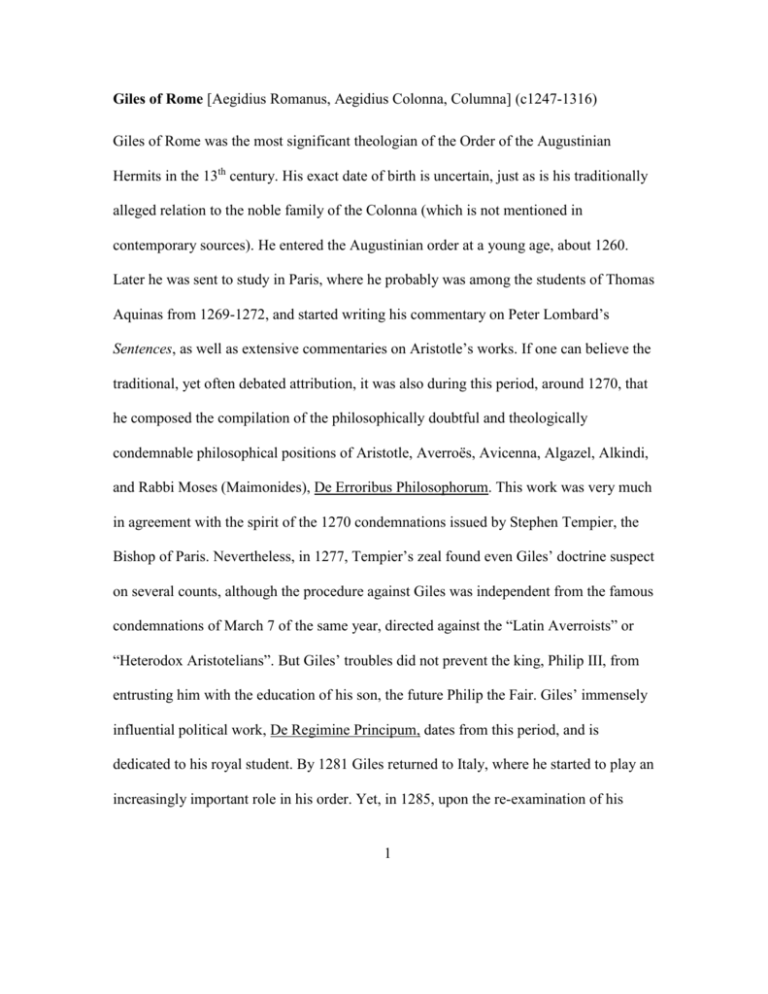

Giles of Rome [Aegidius Romanus, Aegidius Colonna, Columna] (c1247-1316) Giles of Rome was the most significant theologian of the Order of the Augustinian Hermits in the 13th century. His exact date of birth is uncertain, just as is his traditionally alleged relation to the noble family of the Colonna (which is not mentioned in contemporary sources). He entered the Augustinian order at a young age, about 1260. Later he was sent to study in Paris, where he probably was among the students of Thomas Aquinas from 1269-1272, and started writing his commentary on Peter Lombard’s Sentences, as well as extensive commentaries on Aristotle’s works. If one can believe the traditional, yet often debated attribution, it was also during this period, around 1270, that he composed the compilation of the philosophically doubtful and theologically condemnable philosophical positions of Aristotle, Averroës, Avicenna, Algazel, Alkindi, and Rabbi Moses (Maimonides), De Erroribus Philosophorum. This work was very much in agreement with the spirit of the 1270 condemnations issued by Stephen Tempier, the Bishop of Paris. Nevertheless, in 1277, Tempier’s zeal found even Giles’ doctrine suspect on several counts, although the procedure against Giles was independent from the famous condemnations of March 7 of the same year, directed against the “Latin Averroists” or “Heterodox Aristotelians”. But Giles’ troubles did not prevent the king, Philip III, from entrusting him with the education of his son, the future Philip the Fair. Giles’ immensely influential political work, De Regimine Principum, dates from this period, and is dedicated to his royal student. By 1281 Giles returned to Italy, where he started to play an increasingly important role in his order. Yet, in 1285, upon the re-examination of his 1 teachings, Pope Honorius IV asked him to make a public retraction of some of his theses condemned in 1277. The retraction regained for Giles his license to teach, and so in effect it only enabled him to exert an even greater influence in his order and beyond. As a result, the general chapter of the Augustinian Hermits held in Florence in 1287 practically declared his teachings the official doctrine of the order, commanding its members to accept and publicly defend his positions. After serving in further, increasingly important positions, in 1292 Giles was elected superior general of his order at the general chapter in Rome. Three years later, in 1295, the new pope, Boniface VIII, appointed him archbishop of Bourges. As an Italian archbishop in France, and a personal acquaintance of the parties involved, Giles had a difficult role in the conflict between Philip the Fair and Boniface VIII, but on the basis of his theological-political principles, he consistently sided with the pope. On the other hand, after Boniface’s death, he supported the king’s cause against the Order of Templars. In the subsequent years Giles continued to be active in the theological debates of the time, until his death on December 22, in 1316, at the papal Curia in Avignon. Giles’ significance in the history of astronomy lies in his metaphysical investigations into some fundamental physical notions, such as those of matter, space, and time. These investigations, although usually carried out under the pretext of merely providing further refinements of traditional positions, in fact opened up a number of new theoretical dimensions, pointing away from traditional Aristotelian positions. 2 For example, Giles’ interpretation of the doctrine of the incorruptibility of celestial bodies does not rely on the traditional Aristotelian position of attributing to them a kind of matter (namely, ether, the fifth element, quintessence) that is radically different from the matter of sublunary bodies (which were held to be composed of the four elements, namely, earth, water, air, and fire). Since matter according to Giles is in pure potentiality in itself, it certainly cannot make a difference in the constitution of celestial bodies. Therefore, he argues that what makes the difference is that the perfection of the determinate dimensions of these bodies, filling the entire capacity of their matter, renders their matter incapable of receiving any other forms, and that is why they are incorruptible. These determinate dimensions are to be distinguished from the indeterminate dimensions of matter (dimensiones interminatae), the dimensions determining a quantity of matter that remains the same while matter is changing its determinate dimensions in the constitution of an actual body, as in the processes of rarefaction and condensation. The distinction is necessitated by considering that if matter is non-atomic, but continuous, genuine rarefaction or condensation (i.e., diminution or enlargement of the actual, determinate dimensions of the same body without the subtraction or addition of any quantity of matter) can take place only if the changing actual dimensions are distinct from the constant quantity of matter. This interpretation of Averroes’ notion of dimensiones interminatae as the invariable quantity of matter can be regarded as taking a significant step toward the modern notion of mass. 3 Similar considerations apply to Giles’ metaphysical investigations into the nature of time. Motivated by the Aristotelian argument against the possibility of a vacuum on the grounds that free fall in a vacuum would have to be instantaneous, in his hypothetical speculations concerning the possibility of instantaneous motion in a vacuum, Giles transformed the Aristotelian notion of time into a more general idea of a succession of instants, which enabled him to distinguish different orders of time, namely, the proper time of the thing moved, which is the intrinsic measure of its successive motion (mensura propria), and celestial time, which is the extrinsic measure (mensura non propria) of the same motion. Thus, it would be possible for a thing instantaneously moved in a vacuum to cover all intervening spaces successively at different instants of its proper time, which, however, being unextended and not separated by time, may coincide with the same instant of celestial time. This more general notion also enabled Giles to distinguish between time that is the mode of existence of material things, and angelic time, which is the mode of existence of non-material, yet not simply eternal beings. Gyula Klima Fordham University 4 Bibliography Primary Literature Aegidii Romani Opera omnia, Firenze: Leo S. Olschki, 1985Aegidii Romani Quodlibeta, Frankfurt/Main: Minerva, 1966 Aegidii Romani Quaestiones in Octo Libros Physicorum Aristotelis, Frankfurt/Main: Minerva, 1968 Aegidii Romani Quaestio de Materia Coeli, Frankfurt/Main: Minerva, 1982 Secondary Literature Del Punta, F. -- Donati, S. -- Luna, C. 1993: “Egidio Romano”, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 42, Roma: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, pp. 319-341. Donati, S.: “La dottrina di Egidio Romano sulla materia dei corpi celesti. Discussioni sulla natura dei corpi celesti alla fine del tredicesimo secolo”, Medioevo, 12(1986), pp. 229-280. Donati, S.: “La dottrina delle dimensioni indeterminate in Egidio Romano”, Medioevo 14(1988), pp. 149-233. Donati, S.: “Ancora una volta sulla nozione di quantitas materiae in Egidio Romano”, Knowledge and the Sciences in Medieval Philosophy: Proceedings of the 5 Eighth International Congress of Medieval Philosophy (SIEPM), II, edd. S. Knuttila- R. Työrinoja -- S. Ebbesen, Helsinki: Luther-Agricola Society, 1990. Trifogli, C.: “The Place of the Last Sphere in Late-Ancient and Medieval Commentaries”, Knowledge and the Sciences in Medieval Philosophy. Proceedings of the Eighth International Congress of Medieval Philosophy (SIEPM), II, edd. S. Knuttila-- R. Työrinoja -- S. Ebbesen, Helsinki: LutherAgricola Society, 1990, pp. 342-350. Trifogli, C.: “La dottrina del tempo in Egidio Romano”, Documenti e studi sulla tradizione filosofica medievale, 1(1990), pp. 247-276. Trifogli, C.: “Egidio Romano e la dottrina aristotelica dell’infinito”, Documenti e Studi sulla tradizione filosofica medievale, 2(1991), pp. 217-238. Trifogli, C.: “Giles of Rome on Natural Motion in the Void”, Medieval Studies 54(1992), pp. 136-161. 6