Conflicts of interest for statutory office holders

advertisement

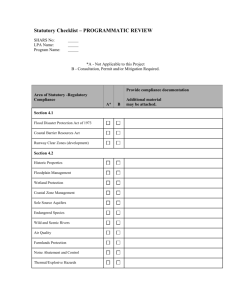

GUIDELINES FOR MANAGING CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS FOR STATUTORY OFFICE HOLDERS 1. Purpose These guidelines are issued to assist statutory office holders in recognising and properly managing the important area of conflict of interest. It is imperative that public confidence be held and maintained in the ability of statutory office holders to act impartially and fairly during any decision-making process or in any exercise of their authority. All statutory office holders should be aware of, and comply with, any obligations contained in legislation establishing an office or any requirements of Codes of Conduct which apply to an office. These guidelines are advisory and in addition thereto. A “statutory office” is defined in section 108 of Public Service Act 1996 as an office established under an Act to which a person may only be appointed by the Governor in Council or a Minister. 2. Conflicts of interest and statutory officer holders The role of statutory office holders is unique. These positions are created under an Act, and persons are required to be appointed by the Governor in Council or a Minister. Statutory office holders perform critical and sensitive roles in Government, often making decisions of vital concern to the community. 3. When conflicts of interest arise A conflict of interest issue is defined by the Public Sector Ethics Act 1994 as a conflict between a person’s private interests and the person’s official duties. The statute establishing an office or the terms of employment will describe the official duties. On occasions a statute will recognise that an individual is appointed to represent the interests of a particular group. This can modify what would otherwise be the ambit of the official duties. In the area of conflict of interest perception is all important. The established test is an objective one, namely whether a reasonable member of the public, properly informed, would feel that the conflict was unacceptable. Essentially it means that such reasonable member of the public would conclude that inappropriate factors could influence an official action or decision. Because the test is an objective one, it matters not whether you as an individual are convinced that with your undoubted integrity you can manage what would otherwise be an unacceptable conflict of interest. The test does not permit you as an individual to be a sounding board. You must step back and objectively assess what a reasonable member of the public might think. Page 1 of 4 It is well known that there are dangers in being a judge in one’s own cause. For this reason you should not hesitate to seek the advice of your peers or supervisors and to keep firmly in mind that the Integrity Commissioner is available to give confidential advice on conflict of interests matters to statutory office holders. There is nothing wrong with being placed in a potential conflict situation. Every statutory office holder has private interests. The important thing is to be able to recognise the potential for a conflict of interest and to manage it appropriately. Failure to do so can lead to drastic consequences in the field of public perception. Private interests are those interests that can bring benefit or disadvantage to an individual, or to others whom they may wish to benefit or disadvantage. These include personal, professional or business interests of the statutory office holder, as well as the personal, professional and business interests of those associates, including family, friends, rivals and enemies. Private interests can be pecuniary, or non-pecuniary. Pecuniary conflicts arise through actual or potential financial loss or gain. Non-pecuniary interests are those that occur through personal or family relationships, or involvement in sporting, social or cultural groups and associations. Examples of private interests include: (1) A person’s interest in property of any kind, including money, the value of which may be altered by a decision, recommendation or advice that person may make or be a party to making. (2) A person’s commercial or business interest of any kind, including a future interest, which could be advanced or harmed by a decision, recommendation or advice that that person may make or be a party to making. (3) A person seeks or accepts gifts and/or hospitality which may influence or appear to influence decision making. (4) A person’s relationships influence or appear to influence a decision, recommendation or advice that person may make or be a party to making. (5) A person’s strongly held personal convictions which may make it difficult or appear to make it difficult for the person to make an impartial decision, recommendation or advice. (6) A person’s capacity to make a financial gain or to prevent a financial loss by using confidential information. (Queensland Integrity Commissioner (2004) Building Integrity in the Queensland Public Sector – A Handbook for Queensland Public Officials, pg 60). Public officials are obliged to put the public interest before any such private interests when carrying out official duties. Public officials serve the public interest when they faithfully perform their official duties. The public interest is the interest of the community as a whole. Page 2 of 4 Statutory office holders should refer to the Act that creates their office for further information of particular public interests their office serves. 4. How to identify conflicts of interests The key method for identifying conflicts of interests is to apply the objective test previously mentioned. A statutory office holder may be faced with conflicts of interest in numerous situations. As a general rule, when a decision, advice or recommendation may help or harm a person with whom the statutory office holder has a relationship or if the officer holder will be effected by the decision, the statutory office holder responsible should not act alone. If a number of people are involved in the decision, recommendation or advice, the nature of the relationship should be disclosed to them. If the statutory body has regulatory, disciplinary or review responsibilities, an office holder should not be involved in making a decision in which the person being considered is a relative, friend or business associate or competitor. The Crime and Misconduct Commission’s Toolkit “Managing Conflicts of Interest in the Public Sector” provides a checklist to help assess whether a conflict of interest exists at page 36 (tool 8.1 - see attached). If there is any doubt as to whether a conflict of interest exists, the office holder should err on the side of caution, declare their interest and take any appropriate management steps. 5. How to manage conflicts of interest When determining the best way of dealing with a conflict of interest, it is important to weigh up the interests of the organisation, individual (including level and type of position held), the nature of the conflict and the public interest. A case by case analysis is required. Firstly, a statutory office holder should refer to the Act that creates their office for guidance. This may provide a process for declaring conflicts of interests. If the office has a Code of Conduct, this should also be strictly adhered to. If no process is provided in legislation, it is important that any conflict of interest is fully disclosed in a timely manner. In some cases there will be a statutory or administrative requirement to lodge a statement of interests. Under the Public Sector Ethics Act 1994, a statutory office holder is able to seek the advice of the Integrity Commissioner on matters relating to conflicts of interest. Such a request must be made in writing, and the Integrity Commissioner will provide a confidential written advice. Alternatively, statutory office holders in the Queensland Public Sector are free to seek independent legal advice in relation to conflict of interest issues on a case by case basis. Page 3 of 4 Another appropriate management strategy is for the statutory office holder to refrain from taking part in activities and decision-making where the conflict arises. Techniques may include abstaining from voting on decision proposals, delegating decision making powers to another officer where the relevant legislation permits, withdrawing from discussion, or restricting access to information relating to the conflict of interest. Finally, it is essential that detailed record-keeping occurs, particularly concerning: Registration of relevant private interests; Disclosure of the conflict of interest; Directions given about handling the conflict of interest; Decisions and arrangements made for resolving the conflict of interest; and Steps taken in implementing the chosen management strategy. 6. Further references Further useful references regarding conflicts of interest include: Welcome Aboard - A Guide to Members of Queensland Government Boards, Committees and Statutory Authorities, available at www.premiers.qld.gov.au The Office of the Queensland Integrity Commissioner - Statutory Office Holders & Conflicts of Interests - Information Sheet No. 3, available at www.integrity.qld.gov.au Building Integrity In the Queensland Public Sector: A Handbook for Queensland Public Officials, available at www.integrity.qld.gov.au The Crime and Misconduct Commission - Managing Conflicts of Interest in the Public Sector: Toolkit and Managing Conflicts of Interest in the Public Sector: Guidelines, available at www.cmc.qld.gov.au Code of Ethical Standards, Legislative Assembly of Queensland, prepared by the Members’ Ethics and Parliamentary Privileges Committee. Page 4 of 4