José Enrique Castro, from the Office of the Prosecutor General

advertisement

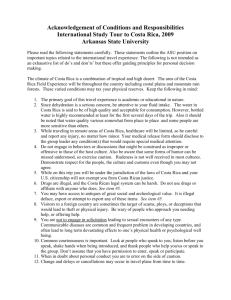

ORDER OF THE INTER-AMERICAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS OF MAY 23, 2001 REQUEST FOR PROVISIONAL MEASURES OF THE INTER-AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS IN THE MATTER OF THE REPUBLIC OF COSTA RICA THE LA NACIÓN NEWSPAPER CASE HAVING SEEN: 1. The communication of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (hereinafter “the Commission” or “the Inter-American Commission”) of March 28, 2001, in which it submitted a request for provisional measures in favor of Mauricio Herrera Ulloa and Fernán Vargas Rohrmoser, respectively journalist and legal representative of the Costa Rican newspaper, La Nación, “for [the Court to request] the Republic of Costa Rica to protect the freedom of expression” of the said persons. The grounds for the Commission’s request were that: a) the journalist, Mauricio Herrera Ulloa, had been criminally convicted of four offenses in the sphere of libel, owing to articles published in the newspaper, La Nación, which reproduced what had been published in the European press concerning a “controversial” Costa Rican public official accredited by the Costa Rican foreign service to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in Vienna; b) the judgment of the Criminal Trial Court of the First Judicial Circuit of San José ordered: 40 days of fines at two thousand five hundred colones a day for each of the four offenses, for a total of one hundred and sixty days of fines and, in application of the rules for this type of proceeding, the penalty was reduced to three times the highest fine imposed, that is to one hundred and twenty days of fines, which would amount to three hundred thousand colones; the civil action for compensatory damages was declared admissible and Mauricio Herrera Ulloa and Periódico La Nación, S.A., represented by Fernán Vargas Rohrmoser, as the persons jointly liable, were condemned to pay sixty million colones for the non-pecuniary damage caused by the publications in the newspaper, La Nación, on May 19, 20 and 21 and December 13, 1995; publication of the operative paragraphs of the judgment in the same section of the newspaper, La Nación, that is, “El País”, and with the same typeface as the articles that were the subject of the dispute, under the responsibility of Mauricio Herrera Ulloa, as the person responsible for the unlawful acts that were committed; that La Nación S.A. withdraw the link that existed between the last name Przedborski and the disputed articles in La Nación Digital on Internet, and that it establish a link between those articles and the operative paragraphs of the judgment. Furthermore, the judgment condemned the defendants to pay one thousand colones towards the procedural costs and the sum of three million eight hundred and ten thousand colones for personal costs; c) the Third Chamber of the Supreme Court of Justice admitted the appeal for annulment filed against the judgment of the Criminal Trial Court of the First Judicial Circuit of San José, but rejected this appeal and, in a judgment of January 24, 2001, confirmed the decision that had been appealed; 2 d) the execution of the criminal judgment convicting the victims was ordered in a “comminatory, non-postponable[,] executable” manner and “forthwith” by the Criminal Trial Court of the First Judicial Circuit of San José, to be executed within three days of notification, which took place on February 27, 2001; e) in response to a petition received on March 1, 2001, the Commission adopted the following precautionary measures: that the State of Costa Rica (hereinafter “the State” or “Costa Rica”) suspend the execution of the guilty verdict until the Commission had examined the case and adopted a final decision on the merits of the matter, o until the State had adopted the necessary measures to annul the judgment voluntarily; that the State abstain from taking any measure addressed at including the journalist, Mauricio Herrera Ulloa, in the Judicial Record of Offenders of Costa Rica, and that it abstain from executing any other act or action that would affect the right to freedom of expression of the journalist, Mauricio Herrera Ulloa, and the newspaper, La Nación; f) in a decision of March 20, 2001, a remedy filed in order to enforce compliance with the precautionary measures of the Commission was declared inadmissible; g) the situation of the journalist, Mauricio Herrera Ulloa, and of Fernán Vargas Rohrmoser, legal representative of La Nación, has deteriorated since the precautionary measures were ordered and is currently “precarious and of imminent risk”; and that the statements of the different judges who are intervening in the case, disregarding the precautionary measures, lead to the conclusion that the judgment may be executed in any moment and that any decision of the Commission, or eventually of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (hereinafter “the Court” or “the Inter-American Court”) will be ineffective since “grave, irreparable damage to freedom of expression” will have been perpetrated; in other words, it will not produce any “useful effect”; and h) that the damage to freedom of expression is clear and imminent, not only with regard to the individual freedom of Herrera Ulloa and Vargas Rohrmoser, but to that of the entire Costa Rican society. i) consequently, the Commission requested the Court to adopt forthwith the following provisional measures: 1) that Costa Rica suspend the execution of the condemnatory judgment delivered by the Criminal Trial Court of the First Judicial Circuit of San José on November 12, 1999, until the Commission has examined the case and, in accordance with Article 50 of the American Convention on Human Rights (hereinafter “the Convention” or “the American Convention”), has adopted a final decision on the merits of the matter or, should the case be referred to the Court, the latter has delivered the corresponding judgment; 2) that Costa Rica abstain from executing any action addressed at including the journalist, Mauricio Herrera Ulloa, in the Judicial Register of Offenders of Costa Rica, and 3 3) that Costa Rica abstain from executing any act or action that would affect the right to freedom of expression of the journalist, Mauricio Herrera Ulloa, and the newspaper, La Nación. 2. The order that the President of the Court (hereinafter “the President”) delivered on April 6, 2001, in consultation with the judges of the Court, in which he decided: 1. To grant the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and the State of Costa Rica until May 12, 2001, to submit the information referred to in considering paragraph 4 of this order. 2. To summon the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and the State of Costa Rica to a public hearing to be held at the seat of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights on May 22, 2001, at 10 a.m., so that the Court may hear their points of view on the facts and circumstances that motivated the request for provisional measures. 3. To request the State, as an urgent measure, to abstain from executing any action that would alter the status quo of the matter until this public hearing has been held and the Court is able to deliberate and decide on the admissibility of the provisional measures requested by the Commission. 3. The Commission’s communication of May 10, 2001, submitted in response to the decisions in the order of the President (supra having seen 2.1). In brief, the Commission indicated in this communication: a) that, essentially, the Convention establishes a system for the protection of human rights and not a system to compensate the violation of such rights, which would operate as a result of violation of the Convention; b) that the principal objective of the protective measures adopted by the Commission and the Court is to avoid a violation being committed or, if applicable, continuing to be committed, until the mechanisms of the interAmerican system of human rights have finished processing the case. c) that the urgency of the provisional measures is self-explanatory, because there is a criminal judgment, an “Order of Execution and Injunction” an order of the Inter-American Commission adopting precautionary measures, two domestic judicial decisions that disregard the precautionary measures ordered by the Commission and reiterate the court order for the immediate execution of the judgment, a decision of the tribunal that heard the case “warning” the alleged victims that “they could become guilty of the offense of disobedience to authority (Disobediencia a la autoridad)”, there is an order of the President of April 6, 2001, adopting urgent measures, and a decision of the Trial Court of the First Judicial Circuit of San José, the tribunal that heard the case, delivered a few days later, on April 24, 2001, establishing the following in its operative section: [i]n compliance with the order issued by [the President of] the Inter-American Court of Human Rights[,] concerning the application of provisional precautionary measures of an urgent nature[,] the suspension of the execution of the judgment and the respective decisions that depend on it are ordered. 4 An imminent threat looms over the alleged victims that a judgment will be executed peremptorily that, prima facie, appears to have aspects that are incompatible with Article 13 of the Convention. The only factor that protects the alleged victims from the violation of their human rights being consummated and preserves them from the “threats” of the Costa Rican court is the order for urgent measures issued by the President; d) that the gravity and the irreparability of the situation refer to individual rights recognized in the Convention that the States Parties have assumed an obligation to respect and guarantee. A serious threat to their right to express themselves freely hangs over the alleged victims, should judgment No. 1320-99 be executed. The explanatory statement of the draft Law for the Protection of the Freedom of the Press, which the President of the Republic of Costa Rica proposed to the Legislative Assembly on November 30, 1998, states that “[i]t has been maintained … that the press is obliged to confirm the veracity of all the news that it obtains from its sources, which is evidently impossible, unless it applies a real self-censorship that would impair the freedom to disseminate information.” If the suspension of the execution of judgment is lifted, freedom of expression and democratic values will be harmed by the necessary delay in processing the case (periculum in mora). There is a reasonable possibility of a risk that the rights alleged by the petitioners will be violated (fumus boni iuris) if the judgment is executed, so that the requirement of extreme gravity is met by the threat to the freedom of expression of the alleged victims; e) that if the judgment is executed, it would cause irreparable damage, effects that could never be eliminated retroactively. The execution of judgment would entail the registration of Mauricio Herrera Ulloa in the “Judicial Register of Offenders”, which would cause him an irreparable harm. The reparation, if appropriate, would not serve for the restitutio in integrum of the harm that could be caused to the alleged victims. Suspension of the execution of judgment until the case has been processed before the inter-American system also promotes the State’s interests, because if it is established that the petitioners were right and that the criminal sentence violates the Convention, the result would be that the payments resulting from the proceeding on compensation that the journalist, Herrera Ulloa, and La Nación must pay to Mr. Przedborski, according to the judgment, would imply that the State and not Mr. Przedborski would be obliged to compensate those who had paid the compensation to the complainant. Although this is not entirely irreparable for the alleged victims, it could entail an unnecessary prolongation of the harmful situation. Moreover, the State would suffer irreparable harm by reimbursing an amount that had been collected by the complainant, over whom the Court lacks jurisdiction; and f) that, with regard to the implications that a decision by the Court on the adoption of provisional measures could have for deciding the merits of the case, the urgent or provisional measures are not an advance notice of the opinion on the merits of the case, but rather a summary pronouncement, based on incomplete knowledge. The suspension of the execution of judgment is required in order to conserve the possibilities of success of the friendly settlement procedure before the Commission; it will also be useful to avoid irreparable damage to the alleged victims and to the State itself, if the organs of the system conclude that the judgment of the domestic courts violated the Convention. Even if the organs of the system conclude that the Convention was not violated, nothing would stand in the way of the subsequent execution of the 5 said judgment, nor would anyone have been caused an irreparable damage. If the Court does not adopt the measures, the judgment is executed and the decision on merits concludes that the said judgment violates the Convention, there will have been an unjustified violation of the human rights of the alleged victims, because a compensatory indemnification would not provide them with the restitutio in integrum of the damages that had been caused. 4. The State’s communication of May 16, 2001, submitted in response to the decisions in the order of the President (supra having seen 2.1), which indicate: a) that the purpose of the Commission’s request is to suspend the effects of a judgment delivered by an independent Judiciary with absolute respect for the norms of due process and for the individual and collective rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution and the human rights conventions; b) that, should the Court order provisional measures, this could prejudge the merits of the matter inasmuch as it is assumed, a priori, that the Court has competence to hear it. The Court could be advancing too far in a proceeding that is only just beginning, and would be indicating that this case has merits to be heard by it; c) that, if the provisional measures are accepted, this could legitimate the use of an extraordinary remedy to annul the execution of a judgment in which neither the life nor the physical integrity of a person is at stake; d) with regard to the extreme gravity, that almost all the Court’s provisional measures have been ordered in order to protect the life or the physical integrity of a person. In the instant case, the sanctions imposed by the Costa Rican criminal court are pecuniary penalties and not burdens that those affected are unable to assume. The registration of Mauricio Herrera Ulloa in the Judicial Registry of Offenders could evidently entail certain limitations or difficulties, but per se does not prevent him from exercising his profession or carrying on his life in society. The fact of being ordered to publish the operative part of the judgment and to link it to the disputed texts does not appear to entail a situation of any gravity or impose a considerable financial burden, but rather it is part of an exercise that could be deemed normal in the context of the same right to information alleged by the Commission in its communication requesting provisional measures. The order to suppress the link in La Nación Digital between the disputed articles and the last name, Przedborski, does not entail a situation of extreme gravity for the company, La Nación S.A., but its suspension could affect Mr. Przedborski’s name; e) with regard to the extreme urgency, the urgency of the required measure is the result of the nature of the situation that motivates it. The Court must evaluate whether there is a situation of urgency where the right to life or to physical integrity is being threatened or violated, which are the grounds that the Court has previously considered in order to call for provisional measures; and f) as for irreparable damage to persons, the possibility of an irreparable damage that could be caused to the alleged victims is not evident. If the InterAmerican Court eventually decides that the judgment of the Costa Rican criminal court violated human rights protect by the Convention, Article 63 of 6 this instrument authorizes the Court to order that the consequences of the situation that constituted the violation of those rights be repaired and fair compensation paid to the injured party. 5. The following persons appeared at the public hearing on this request that was held at the Inter-American Court on May 22, 2001: For Costa Rica: Farid Beirute, Prosecutor General José Enrique Castro, from the Office of the Prosecutor General Arnoldo Brenes, from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Worship Carmen Claramunt, from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Worship For the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights: Pedro Nikken, delegate Carlos Ayala Corao, delegate Ariel Dulitzky, Principal Specialist of the Secretariat of the Commission Debora Benchoam, lawyer of the Secretariat of the Commission Fernando Guier, assistant Witness proposed by the Inter-American Commission: Mauricio Herrera Ulloa 6. The statements made by Costa Rica in the said public hearing, reiterating the arguments set out in its communication of May 16, 2001 (supra having seen 4), and declaring its willingness to comply with whatever the Court decides concerning the request for provisional measures under consideration by the Court. 7. The statements of the delegates of the Inter-American Commission, who indicated that they appeared at the hearing as representatives of the victims, in accordance with the pertinent provisions of the new Rules of Procedure of the Commission, which entered into force on May 1, 2001, and repeated the contents of the Commission’s communication of May 10, 2001 (supra having seen 3). 8. The testimony of Mauricio Herrera Ulloa, who stated that the registration of his name in the Judicial Registry of Offenders of Costa Rica would affect his future exercise of his profession and, in his opinion, also prejudice all his colleagues in the performance of their professional duties, since they would exercise self-censorship for fear of being accused before the courts of justice.1 CONSIDERING: 1. That Costa Rica has been a State Party to the American Convention since April 8, 1970, and recognized the obligatory jurisdiction of the Court on July 2, 1980. 2. 1 That Article 63.2 of the Convention establishes that: In this respect, see the article signed by 119 journalists entitled: “No nos dejan decir…”, published in the newspaper, La Nación, on May 6, 2001. 7 In cases of extreme gravity and urgency, and when necessary to avoid irreparable damage to persons, the Court shall adopt such provisional measures that it deems pertinent in the matters it has under consideration. With respect to a case not yet submitted to the Court, it may act at the request of the Commission. 3. that: That on this issue, Article 25.1 of the Rules of Procedure of the Court establishes At any stage of the proceedings involving cases of extreme gravity and urgency, and when necessary to avoid irreparable damage to persons, the Court may, at the request of a party or on its own motion, order such provisional measures as it deems pertinent, pursuant to Article 63.2 of the Convention. 4. That, under international human rights law, provisional measures are, essentially, not only precautionary in character, in the sense that they preserve a juridical relationship, but also protective, since they protect human rights. Provided that the basic requirements of extreme gravity and urgency and the prevention of irreparable damage to persons are met, provisional measures become a true jurisdictional guarantee of a preventive nature. 5. That, as a result of the public hearing (supra having seen 5), it is necessary to obtain further information regarding the irreparability of the damage that Mauricio Herrera Ulloa might suffer if his name is included in the Judicial Register of Offenders of Costa Rica. 6. That, to this end, the State should submit a report indicating the possibilities contained in the domestic legislation of Costa Rica to avoid or repair, if applicable, the damage referred to, through the powers granted to any of the State’s organs. 7. That, in view of the foregoing, the Court deems that, as a provisional measure, it should maintain the decisions of the President in his order of April 6, 2001 (supra having seen 2), which the Court ratifies in its entirety. 8. That, consequently, the State of Costa Rica must abstain from executing any action that would alter the status quo in the case sub judice until it submits the report referred to in the sixth considering paragraph of this order, by August 16, 2001, at the latest, and this can be considered by the Court in its next regular session to be held from August 27 to September 8, 2001. THEREFORE: THE INTER-AMERICAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS, in exercise of the authority conferred on it by Article 63.2 of the American Convention on Human Rights and Article 25 of its Rules of Procedure, DECIDES: 8 1. To grant the State of Costa Rica until August 16, 2001, to submit the report referred to in the sixth and eighth considering paragraphs of this order. 2. To ratify the order of the President of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights of April 6, 2001, and, consequently, to call on the State of Costa Rica to abstain from executing any action that would alter the status quo of the matter until it has submitted the requested report and the Court can deliberate and decide on this during its next regular session. Antônio A. Cançado Trindade President Hernán Salgado Pesantes Oliver Jackman Alirio Abreu Burelli Sergio García Ramírez Carlos V. de Roux Rengifo Manuel E. Ventura Robles Secretary So ordered, Antônio A. Cançado Trindade President Manuel E. Ventura Robles Secretary