A Critical Analysis Of Internal Control In Bank Trading Information

A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF INTERNAL CONTROL IN BANK TRADING

INFORMATION SYSTEMS IN RELATION TO BOURDIEU’S CONCEPT OF HABITUS

C. Richard Baker

School of Business

Adelphi University

Garden City, New York 11501 USA

Telephone: 1-516-877-4628

E-mail: Baker3@Adelphi.edu

A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF INTERNAL CONTROL IN BANK TRADING

INFORMATION SYSTEMS IN RELATION TO BOURDIEU’S CONCEPT OF HABITUS

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to develop a critical analysis of breakdowns in internal control over bank trading information systems through an examination of a fraud perpetuated by a mid-level derivatives trader at the large French bank, Société Générale, at the beginning of 2008. The theoretical framework for the paper is based on Bourdieu’s concept of

Habitus . The paper explores two research hypotheses regarding breakdowns in internal control over bank trading information systems. The first hypothesis is that cultural differences among countries may lead to a breakdown in controls over trading information systems. The second hypotheses is that there may be a sort of willful blindness in which bank management turns a blind eye to risky trading practices even when there are adequate controls in place to provide early warning signals about the risky practices. Ultimately, we place greater credence on the second hypothesis focusing on the possibility that bank management turns a blind eye to risky trading practices, as long as these practices lead to profits, but that bank management will quickly take action when such practices lead to losses, as was the case in the Kerviel fraud.

2

A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF INTERNAL CONTROL IN BANK TRADING

INFORMATION SYSTEMS IN RELATION TO BOURDIEU’S CONCEPT OF HABITUS

1. INTRODUCTION

In January 2008, Société Générale, the third largest bank in France, disclosed that Jérôme

Kerviel, a mid-level derivatives trader, had lost €4.9 billion (US $7.2 billion), by making unauthorized trades that were apparently not detected, as least initially, by the controls over the bank’s trading information systems. The disclosure of these unauthorized trades revealed a major breakdown in the control over trading information systems in one of the world’s largest banks (Gauthier-Villars et al., 2008a). The purpose of this paper is to examine breakdowns in controls over bank trading information systems through a case study of the fraud perpetuated by

Jérôme Kerviel. The paper explores two research hypotheses concerning the breakdown of controls in bank trading information systems. The first hypothesis is that there may be cultural differences among countries which lead to breakdowns in controls over bank trading information systems. The second hypothesis is that bank management may engage in willful blindness or a type of Nelsonian knowledge

1 in which established controls over trading information systems may be intentionally ignored as long as they result in trading profits, but which are strongly and even retroactively enforced when a loss occurs (Abolafia, 1996).

1 Nelsonian knowledge refers to a story about the famous British Admiral Horatio Nelson, who early in his career at the Battle of Cape St Vincent in 1797, disobeyed a signal that had been raised on the ship of his commander. Nelson withdrew his own ship HMS Captain from the line, ultimately capturing two Spanish battleships. The folklore surrounding the incident alleges that Nelson knowingly placed a telescope to his blind eye and said “I see no ships” to help justify his willful disobedience of orders.

3

2. THE FRAUD AT SOCIÉTÉ GÉNÉRALE

2.1 Background

Société Générale was founded in 1864 during the reign of Napoleon III, the nephew of

Napoleon Bonaparte. The bank became an important source of capital for the France’s rapidly growing economy during the final few decades of the nineteenth century. Just prior to World

War II, Société Générale had 1,500 branches, including several branches in the United States and other countries. Following World War II, the left leaning French government nationalized

Société Générale. In 1987, the government returned the bank to the private sector and by the end of the 20 th

century, Société Générale had reestablished itself as one of the world‘s largest and most important financial institutions. By 2007, the bank operated in almost ninety countries, had total assets of 1.1 trillion Euros, and had more than 130,000 employees worldwide (Société

Générale, 2008).

In the global banking industry, Société Générale and several other large French banks were known for developing a wide range of exotic financial instruments and derivatives. The bank was one of the first to trade equity derivatives, which allow investors to bet on future movements in stocks or markets. Because of their leadership role in the development of financial derivatives, French banks have control of about one-third of the global market for derivative securities, a market that is measured in terms of hundreds of trillions of dollars. These same banks have also become well known for their sophisticated trading information systems which are necessary to maintain control over financial derivatives operations (Société Générale,

4

2008).

Société Générale’s 2007 annual report indicated that nearly 3,000 employees were assigned to control and manage the risks of the bank’s around-the-clock and around-the-globe market trading activities. The most important of these activities were housed in the bank‘s equity derivatives division, which was the its most profitable operating unit. The majority of these control specialists worked in Société Générale’s back office.

The Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Société Générale in early 2008 was Daniel

Bouton a graduate of the École Nationale d'Administration (ENA), one of the most prestigious of the Grande Écoles in France. Bouton began his career with the French Ministry of Finance in

1973, and then he worked at the Finance ministry in various positions until 1991 when he was appointed to be Chief Executive Officer of Société Générale. He became Chairman and of the bank in November 1997 (OECD, 2004b). Société Générale has had a tradition of selecting its officers from France’s most elite schools and universities. Many bankers and traders have had doctorates in disciplines such as mathematics and statistics. They were known as ‘quants’ because of their mathematical trading skills, and they receive large salaries and bonuses. Many of the bank’s top officers, such as Jean-Pierre Mustier, head of trading and investment banking, were former students at the École Polytechnique or the École du Mines, which are two of the most elite schools of higher education in France (Gauthier-Villars and Meichtry, 2008b). Thus it remains a largely un-answered question as to why such highly educated and talented people apparently allowed a massive fraud to be perpetuated by a mid-level derivatives trader from a working class background, who possessed no impressive educational background or credentials.

5

2.2 Anatomy of a Fraud 2

Jérôme Kerviel was born in 1977, and grew up in a working class family in the Brittany region of France. His mother was a retired hairdresser and his late father, Louis, was a metal worker, taking after Kerviel’s grandfather, who was a blacksmith. Kerviel obtained a Bachelor degree in finance at the University of Nantes in 1999. He then completed a university diploma in financial engineering and trading from a second tier business school affiliated with the

University of Lyon. He joined the compliance department of Société Générale in the summer of

2000. In 2005 he transferred to the bank’s trading department in Paris where he became a junior trader. The trading area dealt in program trading, exchange-traded funds, swaps, indexes and quantitative trading. Kerviel earned a bonus of €60,000 on top of a €74,000 salary in 2006, which was considered to be modest in terms of the salaries paid to other traders at Société

Générale and in the financial markets generally. Kerviel’s role was to take positions that were essentially bets on the way that large European stocks would move, particularly in the area of futures contracts tied to a group of shares such as the Euro Stoxx 50. Kerviel also took positions on Germany’s DAX Index and France’s CAC-40 (Gauthier-Villars et al., 2008a).

Kerviel’s initial job at Société Générale was in the operations area or back office. For four years, he was an internal auditor ensuring that the bank’s traders were complying with the bank’s internal control policies and procedures. His responsibilities included monitoring the bank‘s securities trades to identify unauthorized trades; for example, trades that exceeded the

2 This section is based on contemporary accounts written just after the revelation of the Kerviel fraud and appearing for the most part in newspapers and blogs, including: Eyal (2008), Gatinois and Michel (2008), Gauthier-Villars et al (2008), Hanes (2008), Jolly and Clark (2008), Kennedy (2008), Le Monde (2008), Peterson (2008), Routier

(2008), Schwartz and Benhold (2008).

6

monetary limits that had been established for individual traders. In 2004, Kerviel became a securities trader. This new position provided him with an opportunity to make better use of his educational background while at the same time allowing him to escape the back office (Gauthier-

Villars et al., 2008a). (See diagram of red flags raised by the Kerviel fraud on the next page).

Unlike Kerviel, Société Générale’s typical trader was a graduate of one of France’s elite institutions of higher education. In France‘s hierarchical society, one’s educational background and socio-economic status have a disproportionate influence on not only employment

7

opportunities but also the ability to progress within an organization once hired. Kerviel wanted to prove that despite his modest credentials and working class background, he could compete with his well-educated colleagues. After joining the trading division, Kerviel worked hard to impress his superiors. He refused to take advantage of the several weeks of vacation time that he was entitled to each year. By late 2007, Kerviel’s annual salary was approximately 100,000

Euros, which was small in comparison with his fellow traders.

When he left Société Générale’s back office, Kerviel initially joined a relatively minor department within the bank‘s equity derivatives division. The mission of Kerviel‘s new department was to mitigate the risks that Société Générale faced due to its high volume of derivatives trading. Kerviel’s job involved making simple hedges on European stock-market indices. Beginning in 2005, Kerviel began exceeding the maximum transaction size that he had been assigned for individual securities trades as well as engaging in other unauthorized transactions. Because he was very familiar with the internal controls over the bank trading information systems, he was able to use a variety of means to circumvent those controls and thereby conceal his unauthorized trades. These measures included creating false emails from superiors authorizing illicit transactions, intercepting and voiding warning messages triggered by unauthorized trades that he had made, and preparing false documents to corroborate such trades.

In late January 2008, the President of Société Générale, Daniel Bouton, announced that over a period of just three days the bank had suffered losses of more than six billion Euros on a series of unauthorized securities trades made by Kerviel. According to Bouton, Kerviel had used his knowledge of the bank’s internal controls to circumvent the internal control over the bank’s

8

trading information systems. Within two days of Bouton’s announcement, Kerviel was arrested by the French police and he was subsequently convicted of fraud.

In the weeks following the disclosure of Kerviel’s fraud, the bank‘s board of directors established a Special Committee to investigate the fraud. The board retained

PricewaterhouseCoopers to assist this committee. The interim report of that committee revealed that Kerviel was particularly adept at manufacturing explanations for apparent irregularities discovered in his trading activities by back office personnel. Kerviel’s explanations included jargon intended to confuse back office personnel and discourage them from pursuing issues raised by red flags. In addition, the report suggested that back office personnel were intimidated by Kerviel and his trading colleagues, which caused them to be reluctant to vigorously investigate apparent trading irregularities.

The key element Kerviel’s fraud was a technique that has been used in other stock market frauds, namely, recording fictitious transactions that appeared to be hedges or offsetting transactions for unauthorized securities trades that he had placed. For example, if Kerviel purchased a large block of securities, he would then record an offsetting but fictitious sale of similar securities. When he shorted a large block of securities, the fictitious hedge transaction that he recorded would be a long position in those securities or similar securities. These fictitious hedge transactions made it appear as if Société Générale faced only minimal losses on the large securities positions being taken by Kerviel. The ease with which Kerviel could overcome

Société Générale’s back office controls allowed him to take enormous bets on future moves that he anticipated in major European stock market indices. At one point, he had outstanding

9

positions that exceeded the bank’s total shareholders’ equity of 33 billion Euros. In late 2007, he had a one billion Euro gain on a series of unauthorized transactions. During the first few weeks of January 2008, he made several large trades predicated on his belief that European stock market indices would turn sharply higher by late January. Instead, those markets declined, resulting in an unrealized loss of one billion Euros. On Friday, 18 January 2008, Kerviel’s open positions were discovered and reported to Daniel Bouton. Bouton decided that the positions should be closed in order to avoid potentially catastrophic losses for the bank. Over a three-day period,

January 21-23, the open positions on Kerviel’s unauthorized trades were closed. Unfortunately for Société Générale, European stock market prices fell sharply during that three-day period.

Those falling stock prices caused the loss on Kerviel’s January trades to reach six billion Euros, or roughly twenty percent of the bank‘s equity capital.

After closing Kerviel’s open positions, Société Générale publicly reported the massive loss and the fraudulent scheme that had produced it. That disclosure unsettled stock markets worldwide, causing stock prices to fall around the globe. Kerviel’s fraudulent scheme caused the international business press to raise a number of question about Societe Generale’s management team and independent auditors. Among these questions was: how could Société Générale’s supposedly sophisticated internal control over bank trading information systems be overcome by one trader. Likewise, how could the bank‘s independent auditors fail to uncover what appeared to be pervasive deficiencies in the internal control system. Prior to the Kerviel fraud, Société

Générale’s control systems over trading were considered to be among the most effective among major banks. Bank officials maintained that Kerviel overrode internal controls that would have normally produced red flags. These overrides allowed Kerviel to violate credit and size controls

10

in a way such that the bank’s back office did not immediately notice the trades. The unauthorized trades were not detected because Kerviel had knowledge of the bank’s internal control procedures and he knew when checks would be conducted. To hide the unauthorized trades, when he took a position in one direction, he would enter a fictitious trade in the opposite direction to mask the real one. It is also alleged that he used the computer log-in and password controls of colleagues both in the trading unit and the information technology section. Eventually the bank’s internal control procedures led to the discovery that a particular customer (Deutsche

Bank) had unusually large trading balances. When asked about the account balances, Deustsche

Bank denied knowing about the trades. This discovery eventually led to discovery of the Kerviel fraud (Gauthier-Villars et al., 2008a).

3. CULTURAL DIFFERENCES AMONG COUNTRIES AND THE TRANSMISSION OF

CULTURAL CAPITAL

One possible difference between concepts of corporate governance and internal controls in France versus the Anglo-Saxon countries is based on the idea of individual responsibility for fraudulent or illegal acts in the Anglo-Saxon countries versus a greater sense of collective responsibility in France. Shortly after the revelation of the fraud at Société Générale, a survey of readers of the French newspaper Le Monde indicated that a majority of the respondents did not believe that it was possible that a single trader could commit a fraud like that which took place at

Société Générale (Gatinois and Michel, 2008). In contrast, in most Anglo-Saxon countries, there would generally be no fault ascribed to the system as a whole. Typically, at least prior to the most recent financial crisis, it would be assumed that the illegal act or fraud was the fault of a particular individual or several individuals acting in concert. However, after the enactment of

11

the Sarbanes Oxley Act in the United States, which followed a series of several prominent frauds, there has been a greater recognition of the need for an effective system of internal control over both financial reporting and operating activities of companies. However, the ways that the systems of internal control have been implemented appear to be different in different countries.

The background and training of the officers of Société Générale corresponds generally with Bourdieu’s ideas about class distinctions (Bourdieu, 1977)(see the next section for an explanation of Bourdieu’s ideas). Bourdieu maintained that class distinctions are created by the aesthetic preferences that parents convey to their children. According to Bourdieu, class distinctions are determined through a combination of social, economic, and cultural capital.

Society incorporates “symbolic goods, especially those regarded as the attributes of excellence, as weapons in the strategies of distinction” (Bourdieu, 1977, p. 66). Attributes that are considered to be excellent or important are shaped by the interests of the dominant class.

Bourdieu emphasized the significance of cultural capital by arguing that “differences in cultural capital mark the differences between the classes” (Bourdieu, 1977, p. 69). According this view, it is difficult to understand how a trader without an educational or class background from a

Grande École was able to perpetuate a massive fraud, apparently without the knowledge of his superiors.

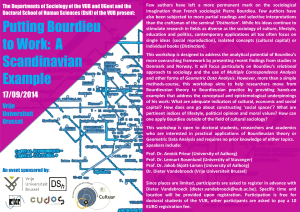

3.1 Bourdieu’s Concept of Cultural Capital

The well known French sociologist, Pierre Bourdieu, developed a highly influential body of work which emphasized the importance of analyzing social practices when engaged in sociological research. Bourdieu stressed the idea that mechanisms of social domination and

12

reproduction involve the interplay of social practices among various actors. Bourdieu opposed

Rational Choice Theory as being grounded in a misunderstanding about how social agents operate. Social agents do not, according to Bourdieu, continuously calculate economic benefits pursuant to explicit rational criteria. Rather, social agents operate according to an implicit practical logic. Social agents act in accordance with their “feel for the game” (the feel being, roughly, ‘habitus’, and the game being the ‘field’)(Bourdieu, 1977, 1991). Bourdieu’s work focused on analyzing the mechanisms of reproduction of social practices and the creation of social hierarchies. In contrast with Marxist analysis, Bourdieu criticized the primacy given to economic factors, and emphasized the capacity of social actors to engage productively with their cultural and symbolic systems. This engagement plays a central role in the reproduction of social structures. What Bourdieu called symbolic violence (i.e. the capacity to obscure the existence of social structures and to accept them as natural, and thus to ensure the legitimacy of existing structures) plays an essential part in his sociological analysis (Bourdieu, 1977, 1991).

For Bourdieu, the social world is divided into ‘fields’ (Bourdieu, 1977). Differentiation between social activities leads to the constitution of various, relatively autonomous, social spaces in which competition centers around particular varieties of ‘capital’. These fields are hierarchical and the dynamics of a particular field arise out of the struggle of social actors who try to occupy the dominant positions within the field. While Bourdieu shares certain beliefs regarding the role of class conflict as derived from Marx, he diverges from analyses that situate social struggle only within economic antagonisms between classes. The conflicts that take place in each social field have specific characteristics arising from within the field which involve social relationships which are not economic. Bourdieu developed a theory of action centered around the concept of

13

‘habitus’. This theory seeks to show how social agents develop strategies which are adapted to the needs of the social worlds they inhabit. These strategies are unconscious and act on the level of instinct (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1990).

Bourdieu argued that different social classes teach different aesthetic preferences to their children (Bourdieu, 1984; Bourdieu and Passeron, 1990). Class distinctions are therefore determined through a combination of varying degrees of social, economic, and cultural capital.

Bourdieu emphasized the importance of cultural capital by stressing that “differences in cultural capital mark the differences between the classes” (Bourdieu, 1977, 1984). Bourdieu’s argued that the acquisition of cultural capital depends upon “early, imperceptible learning, performed within the family from the earliest days of life” (Bourdieu, 1977, p. 66).

Bourdieu argued for the primacy of social origin and culture capital by claiming that economic and social capital, although acquired cumulatively over time, depended upon cultural capital. Bourdieu claimed that “one has to take account of all the characteristics of social condition which are associated from earliest childhood with possession of high or low income and which tend to shape tastes adjusted to these conditions” (p. 177). According to Bourdieu, tastes in food, culture and presentation, are indicators of class, because trends in their consumption seemingly correlate with an individual’s fit in society (p. 184). Each portion of the dominant class develops its own aesthetic criteria. A multitude of consumer interests based on differing social positions necessitates that each fraction “has its own artists and philosophers, newspapers and critics, just as it has its hairdresser, interior decorator or tailor” (pp. 231-32).

14

Bourdieu did not disregard the importance of economic capital. In fact, the production of art and the ability to play a musical instrument “presuppose not only dispositions associated with long establishment in the world of art and culture but also economic means…and spare time” (p.

75). However, regardless of one’s ability to act upon one’s preferences, Bourdieu specifies that

“respondents are only required to express a status-induced familiarity with legitimate…culture”

(p. 63). “Taste functions as a sort of social orientation, a ‘sense of one’s place’, guiding the occupants of a given…social space towards the social positions adjusted to their properties, and towards the practices or goods which befit the occupants of that position” (p. 466). Thus, different modes of acquisition yield differences in the nature of preferences (p. 65). These

“cognitive structures…are internalized, ‘embodied’ social structures”, becoming a natural entity to the individual (p. 468). Different tastes are thus seen as unnatural and rejected, resulting in

“disgust provoked by horror or visceral intolerance of the tastes of others” (p. 56).

Bourdieu believed that class distinctions and preferences are “most marked in the ordinary choices of everyday existence, such as furniture, clothing or cooking, which are particularly revealing of deep-rooted and long-standing dispositions because, lying outside the scope of the educational system, they have to be confronted, as it were, by naked taste” (p. 77).

He believed that “the strongest and most indelible mark of infant learning” would probably be in the tastes of food (p. 79). Bourdieu thinks that meals served on special occasions are “an interesting indicator of the mode of self-presentation adopted in ‘showing off’ a life-style (in which furniture also plays a part)” (p. 79). In summary, likes and dislikes are indicative of class distinctions.

15

Cultural capital derived from social origin affects preferences and surpasses both educational and economic capital. At equivalent levels of educational capital, social origin remains an influential factor in determining certain dispositions. How one describes one’s social environment relates closely to social origin because the instinctive narrative springs from early stages of development. Also, across the divisions of labor “economic constraints tend to relax without any fundamental change in the pattern of spending” (p. 185). This observation reinforces the idea that social origin, more than economic capital, produces aesthetic preferences because regardless of economic capability, consumption patterns remain stable.

3.2 The Transmission of Cultural Capital in the French Business World

The transmission of cultural capital in the French business world is based on a type of meritocracy achieved through education pursued in a Grand École or elite business school. If an individual attends a Grande École, they are usually assured of a position in government, banking or business management. At least half of France’s 40 largest companies are headed by graduates of the École Polytechnique, which focuses on mathematics and engineering, or ENA, the national school of administration. Interestingly, these two schools together produce only about

600 graduates a year, as compared with a graduating class of 1,700 at Harvard Business School.

Being admitted into Harvard, which accepts 9 percent of its applicants, is relatively easy compared with getting into the École Polytechnique. Out of 130,000 students who focus on math and science in French high schools each year, roughly 15 percent do well enough on their exams to qualify for the two- to three-year preparation course required by the elite universities.

Of those who make it through that, 5,000 apply to École Polytechnique, and 400 are admitted.

16

Admission is based strictly on exam grades; there is no essay or interview. There are no legacy admissions, sports scholarships or other shortcuts.

The French business establishment has been described as a close-knit ‘brotherhood’ (it is nearly all male) which shares school ties, board memberships and rituals like hunting and winetasting (Schwartz and Bennhold, 2008). Société Générale’s chief executive, Daniel Bouton, was not only a former student at the ENA; he was a member of the Club de Cent , which is one of the most exclusive business clubs in France. The members of this club include leaders in business, politics and law and its admission procedures are notable in that it is only when an existing member dies that a space is made available for a new member. Officially, the club, founded nearly 100 years ago, is devoted to gastronomy. When the members gather for lunch at Paris restaurants, politics and business are not allowed. Jérôme Kerviel was not a graduate of an elite school or a member of any elite groups like the Club des Cent. The fact that Mr. Bouton and other top managers of Société Générale retained their positions for more than a year after the fraud was revealed in January 2008, prompted criticisms that the French business elite has its own rules (habitus) which act to protect the members of this ‘field’ (Schwartz and Bennhold,

2008; Bourdieu and Passeron, 1990). Daniel Bouton would have most likely been quickly relieved of his position or even pursued legally, if it were a British or American bank (Schwartz and Bennhold, 2008).

3.3 Discussion of Cultural Differences in Internal Control

In 2001, the Enron and WorldCom scandals in the United States undermined the confidence in the capital markets. The US Congress acted to restore confidence by passing the

Sarbanes-Oxley Act in the summer of 2002. This law forced companies with publicly traded

17

shares to spend large amounts of money to strengthen their financial reporting functions and internal control systems.

Many countries subsequently enacted legislation which mimicked the reforms of the

Sarbanes-Oxley Act. The leaders of the French business community also commissioned a study to determine what measures were necessary to strengthen financial reporting, internal controls, and corporate governance among France’s large companies. Many of France’s most prominent business leaders were asked to serve on the committee that would carry out this study. Daniel

Bouton was chosen to chair the committee, and the committee‘s report came to be referred to as the Bouton Report. According to the Bouton Report, many of the reforms included in the

Sarbanes-Oxley Act were unnecessary in France. It was argued that French companies are generally better protected against the risks of excessive or misguided practices due to their well established internal control procedures and practices.

This observation appears to be borne out by the fact that relatively fewer scandals arising from so-called rogue traders have actually taken place in France, apart from the Kerviel case.

Most cases of rogue traders have actually occurred in Anglo-Saxon banks, including Britain and the United States. Consequently, the hypothesis that there are cultural differences among countries which may lead to breakdowns in internal controls over bank trading information systems, seems not be upheld. However, the idea of the difference in ‘habitus’ as proposed by

Bourdieu may be of greater importance, in that because Kerviel came from a background which did not fit the mold of the typical well-educated trader, he may have tried very hard to impress his superiors by making large trading profits for the bank. Ultimately, this effort on Kerviel’s

18

part to impress his superiors, failed due to adverse market conditions which he was unable to anticipate. However, if conditions had been different he might have continued to make large profits from trading, as he did in late 2007 (Gauthier-Villars et al. 2008; Peterson, 2008).

3.4 Discussion of the Hypothesis of Willful Blindness

Kerviel has consistently claimed throughout all of the legal proceedings which have been brought against him, that his superiors’ consciously overlooked his fraudulent activities because he was making profits. Evidence of the possibility of willful blindness can be found in an investigative report issued by PricewaterhouseCoopers in 2008, which revealed that Kerviel’s activities had raised red flags at the derivatives exchange Eurex, the Frankfurt-based derivatives exchange, and also led to 75 internal alerts at Société Générale well before the bank discovered the unauthorized trades in January 2008. Kerviel’s immediate supervisor, Eric Cordelle, admitted that he had been contacted by the bank’s compliance department in November 2007 following an inquiry from Eurex. Eurex was seeking explanations about Kerviel's trades. One trade in particular, a purchase on 19 October 2007, reportedly involved 6,000 DAX index futures contracts valued at over 1 billion euros. However, nothing was done of about this finding and ultimately, France’s banking regulator fined the bank 4 million euros in July 2008 as a result of this trade for having deficient internal controls over trading information systems (Gauthier-

Villars, 2008b).

The PWC report also said that Kerviel’s supervisors had overlooked unusually high levels of cash flow, accounting anomalies, high brokerage expenses, Kerviel’s failure to take a vacation and a huge jump in his trading gains in 2007, when he reported gains of 25 million euros stemming from proprietary trading. The report stated that only 3.1 million of trading

19

profits could be explained by legitimate operations. Kerviel was reported to have made 500,000

Euros through an unspecified one-way trade. The trade breached the banks risk limits.

Ultimately, Kerviel’s immediate supervisors were both fired shortly after the fraud was announced. The Chairman of the bank, Daniel Bouton, was also force to resign in mid 2008. In addition, Jean-Pierre Mustier, head of investment banking, was replaced with Michel Peretie, the former chief executive of Bear Stearns in Europe. Frédéric Oudea, who replaced Bouton in

2008, denied that there was a failure of internal controls. However, after the loss due to

Kerviel’s activities and writedowns from investments in U.S. subprime mortgage products, the bank suffered a 63% decline in 2008 profits compared with a year earlier and it was vulnerable to a hostile takeover bid from BNP Paribas. Société Générale eventually managed to raise 5.5 billion euros through a rights issue and thereby avoided.

There are several factors which can lead to an environment where rogue trading develops, like that present with the Kerviel fraud. Among these factors are: ambiguity and ambivalence .

Many white collar crimes receive an ambiguous amount of censure or punishment. In the case of the rogue trader, Nick Leeson at Baring’s Bank in the 1990s, there was ambivalence by the management of Barings towards Leeson’s trading activities because of the profits that he generated for the bank (Nelken, 1994). This ambivalence towards the trader persisted because of the ambiguity that permeates financial trading. A certain level of ambiguity surrounds the definition, causes, regulation and handling of white collar crime in general, and these factors can be mutually reinforcing. Misconduct can therefore become endemic to the business of bank trading, and ambiguity helps to provide a cloaking device that protects the trading practices from public scrutiny. Scandals in the bank trading sector are usually portrayed as being exceptional rather than structural features of the industry. The bad apple metaphor is frequently applied, but

20

ultimately such metaphors serve as a sort of camouflage regarding white collar crime which leads to high levels of ambiguity. Ambiguity is an inherent feature of banking regulation because the application of many regulatory rules is judgmental. This makes rule ambiguity inevitable because it is difficult to standardize regulation. This uncertainty is underlined in the bank trading sector where innovation and outperformance highly prized. In the securities industry in particular, deviant behavior may not be viewed as criminal, but merely as a type of disequilibrium in the market which requires efficiency adjustments. These systemic tendencies put pressure on banking regulators to establish tolerable levels of deviance. However, the problem is that they then must develop a definition of what actually constitutes misconduct (i.e. what is a deviation from internal control).

Ambiguity also surrounds the notion of intentionality, and while some white collar crimes are intentional it can be difficult to clearly distinguish between behaviors that are intentionally deceptive from those involving incompetence. Consequently, it is in an environment of ambiguity and ambivalence in which rogue trading can emerge. These problems are compounded by the increasing disintermediation of financial markets and the practical difficulties of identifying specific misconduct among the large number of transactions conducted daily, allied with the international nature of much bank trading activities with its attendant problems of jurisdiction. These factors inevitably limit the effectiveness and legitimacy of internal control mechanisms and financial regulatory agencies. Moreover, the compliance and regulatory bodies do not ordinarily have as secure a moral mandate as other enforcement agencies such as the police or other institutional entities which might mitigate the potentially harmful effects of rogue trading. The culture of the bank trading industry is a crucial factor

21

regarding these issues, because tolerance of business misconduct is a question of moral legitimacy and many financial professionals rationalize these activities as being relatively rare.

Hence the second hypothesis explored in this paper, that there may have been willful blindness in the case of the Kerviel fraud seems to be quite likely.

4. Conclusion

The purpose of this paper has been to examine breakdowns in controls over bank trading information systems through a case study of the fraud perpetuated by a mid-level derivatives trader at the large French bank, Société Générale, at the beginning of 2008. The paper has explored two research hypotheses regarding breakdowns in controls over bank trading information systems. The first hypothesis is that cultural differences among countries may lead to a breakdown in controls over bank trading information systems. This first hypothesis was addressed through the theoretical model of “habitus” as put for the by Bourdieu. Ultimately, this first hypothesis was not upheld, in that scandals from rogue trading in France have actually be relatively rare.

The second hypotheses was that there may be a sort of willful blindness in which bank management turns a blind eye to risky trading practices even when there are adequate controls in place to provide early warning signals about the risky practices. The evidence seems to support this second hypothesis in that the management of Société Générale seems to have turned a blind eye to the misconduct of Kerviel as long as he was making a profit for the bank, but that as soon as his trading activities turned to losses, he was fired and charges with significant crimes, for which he will ultimately spend many years in prison. Ultimately, therefore, we place greater emphasis on the second hypothesis which deals with the possibility that bank management turns

22

a blind eye to risky trading practices, as long as these practices lead to profits, but that bank management will quickly take action when such practices lead to losses, as was the case in the

Kerviel fraud.

REFERENCES

Abolafia, M. 1996. Making Markets: Opportunism and Restraint on Wall Street , Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press.

Bourdieu, P. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press.

Bourdieu, P. 1979. The Inheritors: French Students and Their Relations to Culture . Chicago, IL:

University of Chicago Press.

Bourdieu, P. 1984. Distinction: a Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste . Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Bourdieu, P. 1990. Homo Academicus . New York: Polity Press.

Bourdieu, P. 1991. Language and Symbolic Power . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bourdieu, P. and Boltanski, L. 1975a. Le titre et le poste : rapports entre système de production et système de reproduction.

Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales , 1(2): 95 – 107.

Bourdieu, P. and Boltanski, L. 1975b. Le fétichisme de la langue. Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales , 1(4): 2– 32.

Bourdieu, P. and Boltanski, L. 1976. La production de l'idéologie dominante. Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales , 2(2/3).

Bourdieu, P. and Passeron, J-C. 1990. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture .

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bourdieu, P., Boltanski, L. and Maldidier, P. 1971. La défense du corps. Social Science

Information , 10(4) : 45-86.

Comstock, C. 2009. The adventures of Jerome Kerviel: he appeals trial for committing the largest-ever trading fraud by a single person. Forbes.com

,

23

http://www.forbes.com/2009/09/02/jerome-kerviel-fraud-societe-generale-markets-faceslegal.html

, accessed September 2, 2009.

Eyal, J. 2008. Breaking the bank, French style. The Straits Times , 2 February.

Gatinois, C. and Michel, A. 2008.

Société générale : de nombreuses zones d'ombre demeurent.

Le Monde, January 26.

Gauthier-Villars, D. and Meichtry, S. 2008b. Kerviel felt out of his league. The Wall Street

Journal , January 31: C1 .

Gauthier-Villars, D., Mollenkamp, C. and Macdonald, A. 2008a. French bank rocked by rogue trader. The Wall Street Journal , January 25: A1 .

Hanes, A. 2008. Suspect - a fragile being: trader‘s best intentions can go wrong. National Post ,

25 January, A3.

Jolly, D. and Clark, N. 2008. Greater details emerge of bank‘s 4.9 billion loss.

International

Herald Tribune , 28 January.

Kennedy, S. 2008. France‘s SocGen hit by $7.1 billion alleged fraud. Marketwatch.com

, 24

January.

Le Monde. 2008. Société générale : de nombreuses zones d'ombre demeurent. Le Monde ,

January 26: 1.

Nelken, D. 1994. White collar crime. In Maguire, M., Morgan, R. and Reiner, R. (eds), The

Oxford Handbook of Criminology , Oxford: Clarendon Press: 355-392..

Peterson, J. 2008. Societe Generale’s 2007 Annual Report.

jamespeterson.com

, 17 March.

Routier, A. 2008. Jérome Kerviel maintained close relations with his accomplice. Le Nouvel

Observateur , 14 February: http://www.novelobs.com

K. Schlegel and D. Weisburd, (eds), White Collar Crime Reconsidered , Boston: Northeastern University Press,

1992, pp.244-268 at p.247.

Schwartz, N.D. and Bennhold, K. 2008. In France, the heads no longer roll. The New York

Times , February 17, BU 1-7.

24