B221077

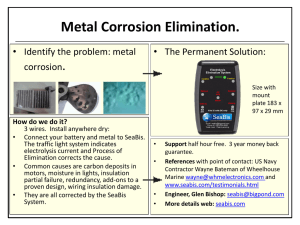

advertisement