1 What contrasting views of women are portrayed in Chretien de

advertisement

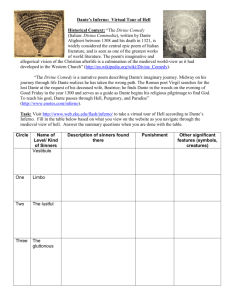

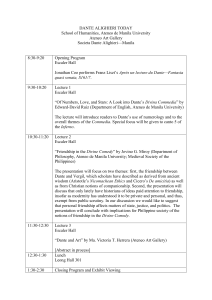

1 What contrasting views of women are portrayed in Chretien de Troyes’ Lancelot, in Hildegard of Bingen’s writings, in Aquinas’s Summa Theologica, and in the Cult of the Virgin as expressed in Gothic cathedrals? Medieval culture portrayed women in contradictory ways. In Aquinas’s Summa Theologica, the writings of Hildegard of Bingen, the Cult of the Virgin in Gothic Cathedrals, and Chretien de Troyes’s Lancelot, the nature of woman is potentially both divine and fallen, although each offers a very different account of the relationship between these qualities. In the Summa Theologica, Aquinas addresses the question whether women should have been created in the beginning by God, considering that the first woman, Eve, occasioned original sin. He answers that woman was made as a helper to man. Women are the “passive power” of generation and the subjects of men. Aquinas adopts Aristotle’s concept toward women, suggesting that the male is the active power in reproduction, and that female gender is determined by some defect in the man’s active power, or by an external influence such as the south wind. According to Aquinas, the male was superior to the female even before Eve was tempted by Satan. However, Thomas still thinks it is necessary for women to exist to show the power of God in turning evil to a good end. Besides, the existence of women increases the diversity of the universe, and thus makes the world become more perfect. In Hildegard of Bingen’s writings and in the Cult of the Virgin in Gothic cathedrals, however, the image of woman is more triumphant. Hildegard establishes a new view of women. She fights against the idea of a woman’s corrupt nature and considers that women are capable of being closer to God than men, as evidenced in her own mystic experiences. She also suggests that the Virgin Mary is the “New Eve,” the 2 “saving lady” who accepts the will of God and saves humankind. By accepting the call of God, Mary brings a blessing that is greater than the harm that Eve did. This concept of Mary as the “New Eve” is also present in the Gothic cathedrals, most of which were dedicated to the Virgin Mary. For example, the central trumeau of the west portal of Notre Dame, Paris, features a sculpture of the Virgin and Child on top of a sculpture of the Temptation of Adam and Eve—suggesting that Mary’s giving birth to Jesus rises above and redeems the original sin of Adam and Eve. In Gothic cathedrals, Mary often seems to be portrayed, in size and dignity, as equal to Jesus. She is even portrayed as the Queen of Heaven. In Chretien de Troyes’s Lancelot, woman is portrayed as a saintly and fallen at the same time. She is depicted as a “prize” for men to attain (by crossing the painful sword bridge, Lancelot can finally face Queen Guinevere) or an inspiration whose watchful presence drives men to achieve. In contrast to Aquinas’s view, here the woman seems to be the more active power. (Lancelot is motivated not by individual glory but by the love of Guinevere; Lancelot fights not for his country but to win the affection of his mistress.) Their passionate meeting at night is described in a mixture of sexual and religious language. However, it is important to remember that Guinevere is married to another man (King Arthur) and that she is committing adultery with Lancelot. In sharp contrast to both Aquinas and Hildegard, Chretien de Troyes uses religious language to portray a woman’s fall into sensuality. 3 Compare and contrast the perspectives on death and judgment offered by Everyman, by Dante’s Divine Comedy, and by Gislebertus’s The Last Judgment, Autun Cathedral France. The perspectives on death and judgment in Everyman, the Divine Comedy, and The Last Judgment in Autun Cathedral are different primarily in two ways: the nature of the protagonist’s journey, and the amount of hope presented. Everyman focuses on a protagonist who represents all Christian souls, at the moment when they are called, by Death, to Judgment. When Everyman is scared by the coming of Death, his fear represents the fear of all people. Everyman meets a number of allegorical figures—Fellowship, Kindred, Goods, Good-deeds—and, one by one, asks them if they will accompany him on his journey. All of them but Good-deeds refuse to go. Good-deeds is willing to make the journey, and the implication is clear: in the end, the only thing a person can take from life is the good that he has done. However, Everyman’s Good-deeds is weak because he has neglected good works. He is therefore instructed by Five-wits to see a priest and receive the church’s sacrament of extreme unction, which will put him on better terms with God. The implication here is clear as well: the Church holds the key to salvation for the individual soul. The Church is the source of hope. In the Divine Comedy, the protagonist Dante goes on a pilgrimage through Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven. Unlike Everyman’s, this is not Dante’s final journey, but a sort of tour through the different dimensions of the afterlife, so he can understand his present life better. Dante is in fact depressed—in a dark wood—at the beginning and in need of a vacation. His first tour guide is the poet Virgil, who takes him through the circles of the Inferno. At the bottom of Hell they encounter Satan stuck in ice that is frozen by wind 4 from Satan’s own wings. They climb over Satan and, crossing the center of the earth, reach the mountain of Purgatory, which Dante suggests was created when Satan crashed through the earth after his fall from Paradise. This mountain becomes a place of hopeful waiting for those souls who are not damned but need to be purified before reaching Paradise. Dante’s tour guide in Paradise is Beatrice, the woman the historical Dante loved. Dante therefore associates God with human love, and when he finally has a vision of God he sees there the image of man. Dante cannot understand how the God can be painted with man’s image—the problem, he says, is like trying to square the circle—but in a flash of light he gains an understanding through the motion of God’s love. The Divine Comedy therefore ends hopefully with a vision of God that shares the nature of mankind and whose power of love moves the universe. In Gislebertus’s The Last Judgment, on the West tympanum and lintel of Autun Cathedral, there is no single protagonist. Instead, there are many people rising from the dead, some going to heaven and some going to hell. In a sense the protagonist is the pilgrim entering this Romanesque cathedral, going on a journey from the secular (west) to sacred (east), and reminded of his ultimate destination by the portal sculpture. The central figure of the carving is Christ, with Heaven to his right and Hell to his left. St. Michael, like the Egyptian god Anubis, is weighing a soul, while a devil tries to tip the scale toward damnation. This sculpture represents a world where it is possible to lose one’s soul; however, situated at the entrance to the pilgrimage church, it serves as a hopeful warning to stay on the right track.