The prevalence of hepatotoxicity on TB

advertisement

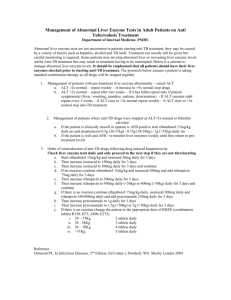

PREVALENCE OF DRUG INDUCED HEPATIC INJURY IN PATIENTS TREATED FOR CO-INFECTIONS OF TUBERCULOSIS AND HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS IN AYDER REFERRAL HOSPITAL ART CLINIC, MEKELLE-ETHIOPIA Minyahil A. Woldu 1*, Addishiwot G. Zewde 2 and Jimma L. Lenjissa1 1 Ambo University, Department of Pharmacy, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Ambo, Ethiopia 2 Mekelle University, Department of Pharmacy, College of Health Sciences, Mekelle, Ethiopia Corresponding Author* Department of Pharmacy College of medicine and health Sciences, Ambo University, P.O.Box: 19 E-mail: minwoldu@gmail.com Tel. (Mobile): +251912648527 Ambo, Ethiopia. 1|Page ABSTRACT Background: Concomitant use of treatment for tuberculosis and antiretroviral therapy is complicated by the adherence challenge of polypharmacy and overlapping side effect like druginduced hepatotoxicity. Objective: To determine the prevalence of hepatotoxicity in patients treated for the co-infections of TB/HIV using serum ALT levels as marker of hepatotoxicity. Result: The most frequent type of hepatotoxicity grade observed was toxicity degree type one, which was observed in 45% of the patients. Five percent of female and 10% male on HAART and anti-TB medications developed hepatotoxicity. Patient in age between 19-62 year were develop almost double the prevalence i.e 10%, compared to 4% in </=18 year and only 1% in age >/=63 year. The prevalence of severe hepatotoxicity (grade 2 or more) was 15 (15%). There was no significant correlation in toxicity grade at baseline ALT measures, (Spearman Correlation Asymp. Sig. (2-sided) = .878). However, the ALT measure after three month showed that significant association with the grades of toxicity, (Spearman Correlation Asymp. Sig. (2-sided) = .000). HCV infection was significantly associated with the risk of hepatotoxicity, which occurred in 3 out of 4 of the study participants (OR, 22.7; P.value, 0.34). Conclusion: The prevalence of hepatotoxcity in the study area was comparable to other similar studies. HBV co-infection was an independent risk factor for hepatotoxicity. Clinicians must consider the possibility of drug-induced liver injury in the management of HIV-infected patients, especially in those with certain risk factors such as co-infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV). Key words: Drug induced hepatic injury, TB/HIV co-infections, Heptotoxicity, Prevalence of drug induced hepatic injury 2|Page INTRODUCTION Worldwide, it is estimated that 14.8% of all new tuberculosis (TB) cases in adults are attributable to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. This proportion is much greater in Africa, where 79% of all TB/HIV co infections are found. In 2007, 456 000 people globally died of HIV-associated TB (1). The advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in the treatment of HIV infection has significantly decreased the incidence of opportunistic infections as well as improved morbidity and mortality among HIV patients (2). However, along with these positive outcomes, HAART is associated with a host of adverse reactions such as hepatotoxicity, hyperlipidemia, hyperglycemia, and lactic acidosis (3). TB is the most common opportunistic infection among people with HIV infection and their coinfection poses many problems with regard to diagnosis, treatment, drug resistance, adverse drug reaction, mortality and burdens on the health systems. Concomitant use of treatment for tuberculosis and antiretroviral therapy is complicated by the adherence challenge of polypharmacy and overlapping side effect profiles of antituberculosis (anti-TB) drugs and antiretroviral drugs. Drug-induced hepatotoxicity (DIH) is one of the overlapping side effects of both antiretroviral therapy (ART) and first line anti-TB drugs leading to interruption of treatment(2, 4-7). The major cause for these are: additive toxicity of the anti-TB and ART medications, overlapping hepatitis C (HCV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections, and other co-administered medications like cotrimoxazole and anti-fungals, as well as alcohol abuse (8, 9). When Hepatotoxicity occur the liver shows an elevation in serum Aaspartate aminotransferase (AST) or Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level from the normal range (AST = 0-37 and ALT< 41 IU/l ) to >3x upper limit of normal in the presence of symptoms, or Serum AST or ALT >5x upper limit of normal in the absence of symptoms (1, 10, 11) . AST/ALT elevations instead of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) elevations favor liver cell necrosis as a mechanism over cholestasis. When AST and ALT are both over 1000 IU/L, the differential can include acetaminophen toxicity, shock, or fulminant liver failure. When AST and ALT are >3X of normal but not > 1000 IU/L, the differential can include alcohol toxicity, viral hepatitis, drug induced, liver cancer, sepsis, Wilson disease, post-transplant rejection of liver, autoimmune hepatitis, and steatohepatitis (non-alcoholic). When AST/ALT elevated are minor it may be due to rhabdomyolysis among many possibilities (12). Therefore, these tests could be used as markers of hepatocellular injury (13). Hepatocellular injury has different grading scale from mild to severe based on the laboratory value of the ALT or AST (14, 15). Studies have revealed that 1420 % of adults on ART had elevated serum liver enzymes as a marker of hepatocellular injury (16). Liver enzyme elevations (LEEs) have been described in association with all major classes of antiretroviral therapy (ART)(4) and anti-TB drugs including isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol. Among the four anti-TB drugs, isoniazid, rifampicin, and pyrazinamide play major role in causing hepatotoxicity (17). However, the complexity of medication used in both ART and anti-TB complicates the understanding of the independent effects of each drug in the development of drug induced liver injury (4). Hepatotoxicity is the major problem associated with TB/HIV co infection. Thus, the purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of hepatotoxicity in patients treated for TB-HIV co infection using the serum ALT level as marker of hepatotoxicity. 3|Page METHODS Study area The study was conducted in Ayder referral hospital of Tigray regional state, Northern Ethiopia, 786 km away from the capital city of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa. Study design A case-control study was conducted. ‘Cases’ were those who develop change in their laboratory value for liver function tests with increment in ALT level from the baseline standards, while ‘controls’ were those who did not change their laboratory value for liver function tests of ALT measurements. Sample size determination The formula for calculating sample sizes Where, p is the Prevalence rate assumed in undiseased (control) groups global studies (14-20%) (7). So, p = 0.2 0r 20% has been taken for this study. K is 1 (control : case ratio = 3 :1) R is the odds ratio Odds to be detected (R = 5) α=0.05 (two-tailed) β = 0.20 (power = 80%) Z1-α is the standard normal value at 95% confidence interval (±1.96) Z1-β is the Z value corresponding to the power of 80% (0.842) Substituting all the values, N becomes 25 (i.e. Triple this number would be included in the control group). Data collection instrument A prepared and pretested checklist was used to collect data from the patient charts and files. Socio-demographic, ART treatment regimen, other co-morbidities and laboratory values for liver function tests were components of the checklist. 4|Page Data organization and analysis Data was compiled, processed, and analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for windows version 16. Descriptive statistics was used to summarize data and statistical analysis using logistic regression was carried out to determine whether there was any association between the dependent and independent variables. A 95% CI and p-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Ethical consideration A formal permission letter was secured from Mekelle University prior to obtaining any information from patients’ medical records and charts. Operational definitions The following WHO operational definitions were used in the study: Toxicity of degree 0: the level of toxicity which is considered as normal in which its value is <1.25 x normal value of ALT in serum Toxicity of degree 1: the Level of toxicity which is considered as weak in which its value is 1.256 – 2.5 x normal value of ALT in serum Toxicity of degree 2: the Level of toxicity which is considered as moderate in which its value is 2.6 – 5 x normal value of ALT in serum Toxicity of degree 3: the Level of toxicity which is considered as severe in which its value is 5.1 – 10 x normal value of ALT in serum Toxicity of degree 4: the Level of toxicity which is considered as severe in which its value is >10 x normal value of ALT in serum Category I anti-Tb drugs: Initial Phase (8 weeks) with INH, RIF, PZA, EMB and Continuation Phase (26 weeks) with INH/RIF or INH/RPT Category II anti-Tb drugs: Initial Phase (8 weeks) with INH, RIF, PZA, EMB and Continuation Phase (26 weeks)with INH/RIF or INH/RPT Category III anti-Tb drugs: Initial Phase (8 weeks) with INH, RIF, PZA, EMB and Continuation Phase (26 weeks) with INH/RIF Category IV anti-Tb drugs: Initial Phase (8 weeks) with INH, RIF, EMB and Continuation Phase (39 weeks) with INH/RIF 5|Page RESULT Background characteristics of the study subjects In this study, 100 patient records were sampled and studied. The mean age of the study subjects was 33.6 + 17 years. The age range was between 4 and 70. More than half of the study subjects 55 (55 %) were females. The most frequent type of TB diagnosed was extra-pulmonary TB (59%) while category one anti-TB regimen was used almost in 85% of the study participants. Sixty two percent of the patients were on WHO HIV stage four and in 94% of the participants ART regiment containing NRTI + NNRTI was used. Only 4% of the patients were positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) test while 79% of them were on cotrimoxazole (CTM) prophylaxis (Table 1). Characteristics of liver function test (ALT test) The most frequent type of hepatotoxicity grade observed was toxicity degree type one, which was observed in 45% of the patients. No hepatotoxicity was observed in 40% of the study participants while only 7% were developed toxicity degree type three, which could result in regimen change, discontinuation or drug desensitization, if it is symptomatic (Fig.1). Determinants of heptotoxicity Five percent of female and 10% male on HAART and anti-TB medications developed hepatotoxicity. Patient in age between 19-62 year were develop almost double the prevalence i.e 10%, compared to 4% in </=18 year and only 1% in age >/=63 year respectively (Table 2). This result may be comparable to the number of participants involved in the study. When we compare the prevalence of hepatotoxicity based on the WHO stage of HIV classification, 11% percent of the patients who develop hepatotoxity were found in stage IV. Fourteen percent of patient develop hepatotoxicity were also on ART combination of NRTIs and NNRTIs. From anti-TB medication category majority i.e 12% were on category one anti-Tb medications. 6|Page Table 1: The background characteristics of patients on anti-TB and HAART medications, Ayder referral hospital, Mekelle-Ethiopia; 2013. Variables age category Sex TB infection Anti-Tb drug regimen WHO staging ART regimen HBV Co-trimoxazole prophylaxis 7|Page Frequency Percent </=18 18 18.0 19-62 69 69.0 >/=63 13 13.0 Female 55 55.0 Male 45 45.0 Pulmonary TB 41 41.0 Extra-pulmonary Tb 59 59.0 Category one 85 85.0 Category two 11 11.0 Category there 4 4.0 Stage one 2 2.0 Stage two 1 1.0 Stage there 35 35.0 Stage four 62 62.0 NRTI + NNRTI 94 94.0 NRTI + PI 5 5.0 NRTI + NRTI 1 1.0 Positive 4 4.0 Negative 96 96.0 Yes 79 79.0 No 21 21.0 Figure 1: Grade of toxicity based on ALT test result of patient on co-medication for HIV/TB infections, Ayder referral hospital, Mekelle-Ethiopia; 2013. 8|Page Table 2: Mean, frequency and standard deviation of ALT, based on degree of toxicity of patients on anti-TB and HAART medications. Ayder referral hospital, Mekelle-Ethiopia; 2013. Toxicity of degree-ALT 0 Mean N Std. Deviation 1 Mean N Std. Deviation 2 Mean N Std. Deviation 3 Mean N Std. Deviation Total Mean N Std. Deviation 9|Page ALT baseline ALT after 33.45 38.30 40 40 17.840 21.042 36.87 68.64 45 45 20.141 45.491 45.12 161.00 8 8 29.479 95.367 26.14 142.43 7 7 16.446 95.446 35.41 69.06 100 100 19.993 61.118 DISCUSSION According to the WHO category of HIV stages, the majority of our study participants 62 (62%) were in stage four (Table 1). In other study the majority were in stage III (71.4%) (4). The toxicity grade observed in our study had similar pattern with previously conducted studies (4). A number of studies reported that the rates of severe hepatotoxicity in TB/HIV co-infected patients receiving both NNRTI based ART and rifampin containing anti-TB drugs concurrently range from 0.6% to 13% (18, 19). In our study the rate of severe hepatotoxicity (grade 2 or more) was 15 (15%) (Table 1), which is a little bit higher. Previous studies from Thailand reported that the rate of anti-TB drug induced hepatitis was 9.2% (20) and the rate of NNRTI associated severe hepatotoxicity was 14% (21). Another study reported that the rate of NNRTI induced severe hepatotoxicity was 20% (7), which is in fact a little bit higher compared to our study (22) . Many patients 40 (40%) had no significant transaminitis at baseline. This result is lower than other similar studies (23). However, the prevalence of transaminitis at baseline with toxicity grade one in our study was 45%, which is a higher compared to other similar studies (23). There was no Grade four transaminitis occurred in our study (Figure 1, Table 2). The mean and S.D of ALT at baseline in hepatotoxicity grade zero patients was (33.45, + 17.84). This result was changed to (38.3, + 21.042) after three months in the same population group. The mean and S.D of ALT change in heptotoxcity grade one patients at baseline and after three months were (36.87, + 20.14 and 68.64, + 45.491) respectively (Table 2). The present study showed that there was no significant correlation in toxicity grade at baseline ALT measures, (Spearman Correlation Asymp. Sig. (2-sided) = .878). However, the ALT measure after three month showed that significant association with the grades of toxicity, (Spearman Correlation Asymp. Sig. (2-sided) = .000) (Table 3). Table 3: Range, mean and standard deviation of baseline ALT test result compared to after three months test of patients on anti-TB and HAART medications, Ayder referral hospital, MekelleEthiopia; 2013. Minimum Maximum Mean Std. Deviation ALT baseline 7 91 35.41 19.993 .878* ALT after 3month 10 301 69.06 61.118 .000* 10 | P a g e Pearson's R and Spearman Correlation Asymp. Sig. (2-sided) The prevalence of HBsAg positive serology in our study was 4% (Figure 2), that was lower than previous conducted study 30 (11.2%) (4). HBV co-infection is a known risk factor for NNRTI induced hepatotoxicity in HIV infected patients (22). In our study HCV infection was significantly associated with the risk of hepatotoxicity, which occurred in 3 out of 4 of the study participants (OR, 22.7; P.value, 0.34) (Table 4) (Figure 2). This figure was lower compared to other previous studies (7). The difference may be due to the variation in study designs. The mechanism of liver injury mediated by HBV infection is related to immune restoration after ART, but the mechanism by which HBV leads to elevated liver enzymes is unclear. It may induce liver damage by a direct cytotoxic effect or by stimulatnoion of immune response (24). 11 | P a g e Table 4: Bivariate and multivariate results of binary logistic regression analysis of patient on comedication for HIV/TB infections, Ayder referral hospital, Mekelle-Ethiopia; 2013 41 5 50 Male 11 34 10 35 age </=18 3 15 4 14 19-62 19 50 10 59 .05 >/=63 3 10 1 12 -.37 HIV stage Stage one 1 1 0 2 Stage two 0 1 0 1 -19.62 Stge there 6 29 4 31 Stage four 18 44 11 51 Type of TB Pul.TB 8 33 5 36 Extra-Pul. TB 17 42 10 49 ART reg. NRTI+NNRTI 25 69 14 80 NRTI +PI 0 5 1 4 .65 NRTI +NRTI 0 1 0 1 .00 TB drugs reg. Cat I 18 67 12 73 Cat II 7 4 2 9 -.58 Cat III 0 4 1 3 HBV Positive 4 0 3 1 Negative 21 75 12 84 CTM Yes 22 57 12 67 No 3 18 3 18 Cat=category 12 | P a g e Reg. =regimen S.E. df No Wald 14 Yes Control Female Variables Sex B Cases Hepatotoxicity .75 .694 Sig. Exp(B) 1.165 1 .281 .111 2 .946 .879 .004 1 .952 1.054 1.148 .101 1 .750 .694 .628 3 .890 .0004 .000 1 1.000 .000 -20.43 .0004 .000 1 1.000 .000 -.86 1.085 .628 1 .428 .423 -.89 1.046 .737 1 .391 .407 .277 2 .871 1.227 .277 1 .599 1.907 .00057 .000 1 1.000 1.000 .515 2 .773 1.238 .223 1 .637 .558 .82 1.470 .311 1 .577 2.271 3.13 1.476 4.497 1 .034* 22.862 -.497 .781 .404 1 .525 .609 CTM=cotrimoxazole *=significant 2.116 Figure 2: The prevalence of hepatotoxicity in HBV infected and non infected patients of patients on anti-TB and HAART medications, Ayder referral hospital, Mekelle-Ethiopia; 2013. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATION In our study the main factor determining the risk of hepatotoxicity in HIV-TB co-infected patients apart from the inherent hepatotoxic nature of first line anti-TB and ART medications was HBV infection. Therefore, we can conclude that HBV co-infection is an independent risk factor for hepatotoxicity in our study of TB-HIV co-infected patients. Clinicians must therefore consider the possibility of drug-induced liver injury in the management of HIV-infected patients, especially those with certain risk factors such as co-infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis B virus (HBV). 13 | P a g e ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome ALT Alanine Aminotransferase ARH Ayder Referral Hospital ART Antiretroviral Therapy ARV Antiretroviral AST Aaspartate Aminotransferase CTM cotrimoxazole HAART Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy HBV Hepatitis B Virus HBsAg Hepatitis B Surface Antigen HIV Human Immune Deficiency Virus NNRTI Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor NRTI Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor TB Tuberculosis ULN Upper Limit of Normal ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 14 | P a g e We would like to thank Mekelle University, College of Health Sciences and department of pharmacy, and Ayder referral hospital academic, medical and administrative staffs. DECLARATIONS Funding: None Competing interests: None declared Ethical approval: Not required 15 | P a g e REFERENCES 1. Pozniak A, Coyne K. British HIV Association guidelines for the treatment of TB/HIV co infection. British HIV Association HIV Medicine 2011;12:517-24. 2. Sharma SK, Singla R, Sarda P, Mohan A, Makharia G, Jayaswal A, et al. Safety of 3 Different Reintroduction Regimens of Antituberculosis Drugs after Development of Antituberculosis Treatment-Induced Hepatotoxicity. Clinical Infectious Diseases.50(6):833-9. 3. Chu KM, Manzi M, Zuniga I, Biot M, Ford NP, Rasschaert F, et al. Nevirapine- and efavirenz-associated hepatotoxicity under programmatic conditions in Kenya and Mozambique. International Journal of STD & AIDS.23(6):403-7. 4. Wondemagegn Mulu, Bokretsion Gidey, Ambahun Chernet, Genetu Alem, Bayeh Abera. Hepatotoxicity and Associated Risk Factors in HIV-infected Patients Receiving Antiretroviral Therapy at Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital, Bahirdar, Ethiopia Ethiop J Health Sci. 2013 23(3):217-26. 5. National center for HIV/AIDS vh, STD and TB prevention. National center for HIV/AIDS, viral hepatitis, STD and TB prevention; 2007 [cited 2013 May 27]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/tb/TB_HIV_Drugs. 6. Y. M. The interaction of HIV and tuberculosis.HIV Prevention Research Unit. Medical Research Council of South Africa. 2008;3(12): 565-6. 7. Mankhatitham W, Lueangniyomkul A, W. M. Hepatotoxicity in patients co-infected with tuberculosis and HIV while receiving Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy and Rifampicine-containing anti-tuberculosis regimen. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2011;42(3):651-58. 8. Price J, C. T. Liver Disease in the HIV–Infected Individual. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hematology. 2010;8:1002–12. 9. Lima M, H. M. Hepatotoxicity induced by anti tuberculosis drugs among patients co infected with HIV and tuberculosis. . Cad Saúde Pública, Rio de Janeiro.28(4):698-708. 10. Pozniak A, Coyne K, R M. British HIV Association guidelines for the treatment of TB/HIV co infection. British HIV Association HIV Medicine. British HIV Association HIV Medicine. 2011;12:517–24. 11. Mankhatitham W, Lueangniyomkul A, Manosuthi W, Hassen Ali A, Belachew T, Yami A, et al. Hepatotoxicity in patients co-infected with tuberculosis and HIV-1 while receiving nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy and rifampicin-containing anti-tuberculosis regimen. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1371;42(3):651-8. 12. Nyblom H, Björnsson E, Simrén M AF, Almer S, R O. The AST/ALT ratio as an indicator of cirrhosis in patients with PBC. Liver Int. 2006;26(7):840-5. 13. Zechini B, Pasquazzi Z, A. A. Correlation of serum aminotransferase with HCV RNA levels and histological finding in patients with chronic hepatitis C: The role of serum Aspartate transaminase in the elevation of disease progression. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;16:91- 6. 14. Tostmann A, Boeree M, R A. Anti tuberculosis drug-induced Hepatotoxicity. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2008;23 192–202. 16 | P a g e 15. W. L. Drug-Induced Hepatotoxicity. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349(5):474-85. 16. MS S. Drug-induced liver injury associated with antiretroviral therapy that includes HIV1 protease inhibitors. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:90–7. 17. Khadka J, Malla P, Jha SS, SR P. The Study of Drug Induced Hepatotoxicity in Patients Attending in National Tuberculosis Center in Bhaktapur. Lung DisHIV/AIDS 2009 4(2):17-21. 18. Shipton LK, Westor CW, Stock S, al. e. Safety and efficacy of nevirapine- and efavirenzbased antiretroviral treatment in adults treated for TB-HIV co-infection in Botswana. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13:360-6. 19. Moses M, Zachariah R, Tayler-Smith K, al. e. Outcomes and safety of concomitant nevirapine and rifampicin treatment under programmed condition in Malawi. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14: 197-202. 20. Krittiyanant S, Sakulbamrungsil R, Wongwi-watthananukit S, W. S. Risk factors of antituberculosis drug-induced hepatotoxicity in Thai patients. Thai J Pharm Sci 2002;26( 121-8). 21. Law WP, Dore GJ, Duncombe CJ. Risk of severe hepatotoxicity associated with antiretroviral therapy in the HIV-NAT Cohort. AIDS Clinical Care. 2003;17:2191-9. 22. Ena J, Amador C, Benito C, Fenoll V, F. P. Risk and determinants of developing severe liver toxicity during therapy with nevirapine - and efavirenz- containing regimens in HIVinfected patients. Int JSTD AIDS 2003;14:776-81. 23. R Kalyesubula, M Kagimu, KC Opio, R Kiguba, CF Semitala, WF Schlech a, et al. Hepatotoxicity from first line antiretroviral therapy: an experience from a resource limited setting. Afr Health Sci. 2011;11(1):16-23. 24. MK. J. Drug-induced liver injury associated with HIV medication. Clin Liver Dis. 2007;11:625-39. 17 | P a g e