Appendix 1 - University of Leeds

advertisement

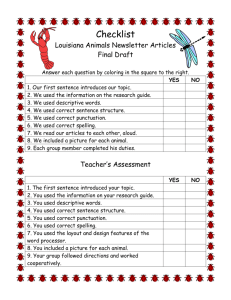

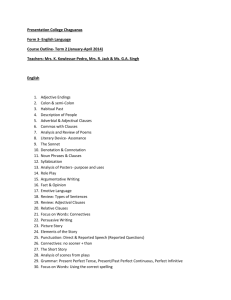

Accuracy in Key Stage 3 Writing: a case study of students' writing in a mixed secondary school Wasyl Cajkler and Chris Comber (University of Leicester) Paper presented to BERA, September 2003 Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh In recent years, concerns about the accuracy of students’ writing in Key Stages 2 and 3 have been expressed in a variety of reports, (OfSTED 1999: 6; 2002; QCA, 2002). HMI (2000) indicated that the teaching of writing in primary school was a significant concern, reporting that too many pupils were unable to produce sustained accurate writing by the end of Key Stage 2. The 1999 OfSTED evaluation of the first year of the National Literacy Strategy noted that it was uncommon to see elements of the writing process being taught as part of a sequence of lessons: ‘Pupils were rarely required to produce grammatically complex sentences, showing different types of sentence connectives, adverbial phrases, imaginative vocabulary, precise use of language or an understanding between standard English and colloquial use of dialect forms’ (paragraph 84, page 15). Allen (2002: 6) acknowledges concerns about literacy especially in relation to underachieving boys in secondary English, in particular their writing skills. Since the introduction of the National Literacy and KS3 Strategies, there has been greater focus on formal features of language in writing (e.g. Grammar for Writing, DfEE, 2000). The National Curriculum expresses the expectation that during KS3 and 4, students will learn to write Standard English correctly, using appropriate ways of presenting their work. ‘Students should be taught about the variations in written standard English and how they differ from spoken language, and to distinguish varying degrees of formality, selecting appropriately for a task’ (NC English, 1999, p. 38). In addition, students are taught word classes and their grammatical functions. They should also be taught to recognise standard and non-standard grammar. When teaching Standard English, teachers are advised of the following common non-standard usages that occur in England: subject-verb agreement (e.g. they was) formation of past tense (have fell, I done) formation of negatives (ain’t) formation of adverbs (come quick) use of demonstrative pronouns (them books) use of pronouns (me and him went) use of prepositions (out the door) (ibid.: p. 32). Literacy Across the Curriculum (DfEE, 2001) also expressed concerns about formal features in students’ writing such as grammar, punctuation, spelling and paragraphing. Allison, Beard and Willcocks (2002) argue for the investigation of students’ writing in order to assist schools in designing programmes to promote writing. Their study of the use of subordinate clauses by 7-9 year olds concluded that children may benefit from targeted approaches that seek to develop this skill in children’s writing. More importantly, they argue that teachers can quite significantly influence the development of writing of their students through “levels of expectation, the careful provision of tasks and the quality of intervention” (2002: 110). There are concerns about writing development being left to chance. Alexander and Currie cite the work of Nightingale (1998) saying that if writing is just left to look after itself “the 1 outcome will be writers who just ramble on” (p. 43). The more teachers know about students’ writing, the better prepared they can be to intervene to support the development of writing. So, interest in secondary school children’s writing has grown in recent years and has undoubtedly been promoted by the emergence of SATs and the work of the QCA in assessing end of Key Stage assessments of children’s writing. Reporting on KS3 writing, the QCA (2001, 2002) identified a number of trends in children’s writing with regard to punctuation. These included: 75% correct use of full stops to end sentences; spelling errors at between 4 and 5 per hundred words; inappropriate use of the comma or failure to use full stops; omitting 45% of commas used to demarcate clauses; difficulties with the apostrophe particularly the possessive apostrophe; difficulties for some learners in managing complex sentences. Part of the case study reported in the present paper sought to discover the extent to which the above features were evident in the writing of 12-14 years in one school, as well as grammatical errors and intrusions from non-standard English (NSE). One of the most informative recent studies of accuracy in writing was the Technical Accuracy Project (QCA, 1999, a, b), which studied English GCSE scripts (course work and final tasks for the 1998 examination) of 144 candidates at borderline grades of A, C and F. The study explored the performance of students in punctuation, spelling, sentence and clause structure, use of word classes, textual organisation, paragraphing and occurrences of non-standard English. While – somewhat predictably – the research found a positive association between grade and accuracy, it was also able to identify typical differences between the three grades. For example ‘A’ grade writers made one spelling error per hundred words, while ‘F ‘grade writers made six errors per hundred (1999a: 6). When punctuating, the less successful writers had a tendency to omit full stops or to use a comma splice. Less successful writers wrote shorter sentences and used more finite verbs than A grade candidates. The study In the light of concern about literacy standards, we were invited to investigate writing in a mixed secondary school. The background to the investigation was a concern in the school about boys’ relative underachievement in this area. This latter issue, discussed in some detail in an unpublished report to the school and briefly addressed here, will be reported in a forthcoming paper. The main focus of the present conference paper, however, is the accuracy of pupils’ writing in terms of punctuation, spelling and grammar, and potential strategies for improving these aspects of writing. Methods The investigation was conducted during the spring and summer terms of 2002 involving a range of data collection procedures: Questionnaire survey of students’ attitudes: This explored students' attitudes towards school and schooling, with a section particularly focussed on aspects of literacy. Semi-structured interviews with selected students: The interviews extended issues raised in the survey, and concerned attitudes towards and experiences of school and learning in general, with a specific focus on literacy. 2 Semi-structured interviews with selected staff: Members of the management team along with teachers representing a range of curriculum areas were interviewed about attitudes and strategies for addressing literacy deficits. Observations of classroom practice in selected lessons. Analysis of school documentation: including the school literacy strategy, the school development plan (SDP), and the Performance and Assessment (PANDA) report. Examples of student writing: A distinction was made between what we termed ‘rehearsed writing’ (homework or coursework) and ‘unrehearsed writing’ which was writing that we elicited during one of our visits to the school. It is with the examples of student writing that the present paper is concerned, drawing principally on analysis of writing taken from Years 8 and 9. Students were asked to write a short piece of personal or narrative writing, with no in-class input, preparation or rehearsal other than a choice of tasks (see Appendix 1). 35 pieces of 'unrehearsed' personal or narrative writing, elicited from groups in Years 8 and 9, were analysed for content, register and accuracy of expression. These samples of writing were taken from the whole ability range and from both boys and girls, 6 of the 35 students appearing on the schools’ register of special needs. Each piece of writing was then assessed against current National Curriculum criteria and was further analysed with regard to spelling, punctuation, use of conjunctions, clause and sentence structure (simple, complex and compound) and use of paragraphs, using the Technical Accuracy Project’s coding schedules (QCA, 1999b). Following these analyses, three stratified samples of homework from each year group, selected as representing high, mid and low levels of writing ability, were examined against similar criteria. 11 students provided samples of homework or coursework in the following subjects: RE (4), English or English Literature (14), Geography (12), Science (4). We were interested to discover to what extent students in Years 8 and 9 were able to produce sustained accurate writing. For this paper, we have focused principally on errors and clause use. Findings Accuracy in students’ unrehearsed writing This section reports on the sentence level features analysed. A difficulty with this type of analysis is that some of the observations are subjective. As a result, while findings about spelling can be treated with some degree of certainty, those relating to punctuation need to be tempered with observations about the variations of native speaker practice in punctuation, most notably with regard to the use of the comma to demarcate clause boundaries. Grammar for Writing (DfEE, 2000) and the Year 7 Sentence Level Bank (DfEE, 2001) offer advice on this issue with great firmness but there is a significant amount of variation in actual usage. Clause Use Clause use in Year 8 and 9 unrehearsed writing is summarised in the following table. Table 1: Clause use in unrehearsed writing Year-group & gender Total clauses Identifiable sentences Clauses co-ordinated with ‘and’ 3 Subordinate conjunction Non-finite clauses Relatives Year 8 Boys Year 8 Girls Year 9 Boys Year 9 Girls Total 121 234 461 352 1168 70 96 191 153 510 28 49 54 49 180 13 (11%) 52 (22%) 103 (22%) 66 (19%) 234 (20%) 14 (11.5%) 22 (22%) 36 (8%) 41 (12%) 113 (10%) 4 4 24 21 53 Clauses not accounted for above occurred in simple sentences of which there were 160 or 14% of all clauses, or were co-ordinated in other ways (notably with but and or). Alternatively, they formed part of poorly punctuated sentences with comma splices. Some students presented in a number of clauses in unpunctuated waves, for example: He lost his balance and went tumbling to the ground with his bike on top of him he couldn’t get up because his leg was throbbing because it got stuck under the bricks he shouted for help but no one heard him it was getting quite dark and cold now and he thought he would be there all night so he yelled again and a man came rushing over and helped him and took him to his house. Arguably, the above text has 15 clauses. There is evidence of development in the use of subordinate clauses (two with because and one Ø-that after thought) but also overuse of and. The effects of the latter, however, would be softened by use of full stops to divide the text into five sentences rather than one. Greater accuracy in the use of the full stop would have enhanced a significant amount of the writing (see table 5 and the section on punctuation). What was also striking from the year groups as a whole was the still relatively small but emerging number of subordinators and the greater use of relative clauses in Year 9. There were some non-finite clauses (10% of all clauses). Of these, 31 out of 113 were different types of nominal to-infinitive clauses after want, would like, decided and other similar verbs. Girls were more ambitious in writing complex sentences. 22% of their Year 8 clauses included a subordinating conjunction and 9% of all clauses were non-finite, signs of linguistic maturity (Perera, 1984; Beard, 2000) but use of relative clauses was limited. Boys wrote much more in Year 9 and displayed a number of features deemed to be more mature in terms of writing, for example the appearance of some non-finite clauses (8% of all clauses) and more varied use of subordinate clauses (22% of all clauses) and relative clauses (5%). For a list of principal subordinating conjunctions found in the different types of writing analysed see Appendix 4. Errors In Year 8, boys made an error every 16 words, of which 18% were grammatical errors (12 0ut of 68 errors). By far the largest number of errors fell into the domains of punctuation (30), (14 of which were associated with capital letter misuse but usually not sentence initial) and spelling (26), accounting for just over 80% of errors. Table 2: Unrehearsed sentence level errors by Year and Gender Year-group & gender Year 8 Boys Year 8 Girls Year 9 Boys Year 9 Girls Total 11 8 8 8 NC Level Mean 4.18 4.25 4.25 4.75 Words No. of Errors 68 164 212 145 1060 1451 2658 2231 Grammar 12 19 14 16 Punctu ation 30 85 103 57 Spelling NSE 26 56 93 62 3 4 2 10 Despite the punctuation errors, Year 8 boys wrote 70 sentences, 64 of which were correctly opened and closed (initial capital and full stop). 4 Girls made more errors per word than boys in Year 8, every 9 words, though this was largely accounted for by two writers with particular needs, who made 104 errors, principally of spelling (44) and punctuation (49). Taking away these two contributions the average for girls approached that of boys at 14 words per error. In Year 8, 11% of girls’ errors could be attributed to grammar but only four of the errors could be attributed to influence from non-standard English. Again, most fell into the categories of spelling (56) and punctuation (85). Year 9 boys made 212 errors in 2658 words, but only 14 were grammatical. Punctuation and spelling accounted for most of their errors, which occurred at the rate of 1 to every 12 words. Grammar and non-standard English intrusions accounted for very few. Girls fared much better in the year 9 group making one error per 15 words. The higher number of NSE intrusions is largely accounted for by the use of colloquial adjectives such as ‘rank’ ‘slaggy’ ‘well-excited’ and ‘scabby’ which featured in the writing of two girls only. There were signs of increasing maturity. 19% of clauses were subordinate, while almost 12% were non-finite, the latter being higher than the boys’ 5% at this stage (see Table 1). Error Types In all the unrehearsed writing (7424 words), 600 errors were identified (an error every 12.4 words) but only 61 could be attributed to grammar. 48 errors related to difficulties with the apostrophe. Only 10% of errors were strictly attributable to difficulties with grammar and six writers had no grammatical errors at all, not even slips or word omissions. A full list is provided at Appendix 2. Table 3: Unrehearsed Writing Years 8 and 9: summary of errors Total errors Grammar Punctuation Apostrophe Capitals Spelling Homophones 600 61 280 48 65 211 26 Other: e.g. colloquialisms (16), cohesion, odd words 48 In line with Williamson and Hardman’s (1997a and 1997b) research, we found very little intrusion from non-standard English forms. The colloquial was stood, had fell and omission of preposition in out his arm occurred and are probably instances of transfer from local dialect use. There were a number of colloquialisms but the grammar was not incorrect (use of shortened forms such as cause, cos and some inappropriate adjectives used by young people (rank, scabby and so on). Use of tenses was generally appropriate and accurate. Other errors (for example the omission of verbs) could be ascribed to performance slips associated with first drafting e.g. the omission of words such as parts of verb chains which could be improved through careful editing, as in: …he could back to his house … Perhaps surprisingly, 12 errors occurred with determiners, either through omission or by failure to use ‘an’. It is perhaps arguable that some of these errors could be viewed as typographical slips rather than grammatical. Williamson and Hardman (1997a: 5), reporting on the work of twenty-three Year 11 writers, found an error incidence rate of 13.7 words per error and 8.9 words per error in the writing of Year 6 learners. Spelling, punctuation and other orthographic features, in which they included apostrophes, accounted for 76.3% of their sample’s errors. The Year 8 and 9 students in our study averaged 12.4 words per error in unrehearsed writing and 24 words per error in their course work. If capitals, punctuation and apostrophe errors are aggregated they account for 5 46% of the current sample’s difficulties. Spelling and punctuation combined account for 82% of all errors (including misuse of omissive and possessive apostrophes). Distribution of errors Errors were not evenly distributed or confined to students performing at lower National Curriculum levels. This distribution suggests that attention to some of these issues would benefit a wide range of learners. For example, one Year 9 level 6 writer made seven errors with possessive apostrophes, another working at levels 3/4 regularly used ‘ent’ in place of the omissive apostrophe e.g. he couldent. An intrusive apostrophe (e.g. When he come’s round) was a feature of one girl’s writing, although her writing was otherwise judged to indicate a level 5/6 standard. Although error occurrence was randomly spread, looking at who was affected by which errors gives a slightly different view of inaccuracy. For example, while grammar errors were relatively infrequent they were widely scattered but they were not as frequent as spelling and punctuation mistakes which seemed to affect the whole population. Table 4: Error Spread in Years 8 and 9 (n. 35) Error Grammar Apostrophe Spelling Punctuation Capitals Numbers of students affected 27 (13 with one error only) 18 35 28 17 No of students not affected 8 17 2 7 18 Three students managed to avoid both punctuation and capital letter errors, writing 317 words between them. One student who wrote 44 words managed to avoid grammar and apostrophe errors, as did another Year 8 student writing 75 words. One Year 9 boy wrote 367 words without errors in grammar and apostrophe use but had fourteen errors in both spelling and punctuation. Punctuation There were 400 correctly demarcated sentences with clear full stops (out of a possible 510). Numbers in brackets in table 5 indicate the number of students affected. Table 5: Punctuation in Years 8 and 9 Appropriate full stops Omission of full stop Comma splice Intrusive full stops Omission of comma Omission of non-sentence initial capitals (e.g. proper nouns, I, or inappropriate capitals as in daft as a Bat Year 8 132 21 (7 students) 16 (5) 3 27 (5) 33 Year 9 268 44 (8) 35 (10) 6 21 (8) 32 Total 400 65 51 9 48 65 The figures suggest that 22% of sentences are not clearly demarcated by full stops, roughly in line with QCA reports (2001, 2002) and not dissimilar to the findings of the Technical Accuracy Project (QCA, 1999a). We found that 22 students made errors with sentence demarcation: comma splicing, omitting full stops or both (seven students did both). 13 punctuated accurately, without error. Taken overall, these Year 8 and 9 students performed in 6 line with the national pattern of 75% correct sentence demarcation, achieving 78% correct demarcation in their unrehearsed writing. The above findings reveal relatively light difficulties with grammar, especially if one sets aside the number of errors arising from confusion about apostrophe use (40). When analysing punctuation, principal difficulties for younger writers occurred with the organisation of long sentences. Perera (1984: 235) talked about children losing their way more often in complex sentences than in simple sentences. In the present study this was not uncommon in Year 8 but decreased in Year 9 narrative writing. Nevertheless, a Year 9 boy wrote a very engaging story but had difficulties with sentence co-ordination and punctuation: When he went back to his school his friends were amazed. He heard stories going around the School Saying he was a hero and he decided it should stay that way but he was the only that knew what had happened it was Alan being clumsy. Many native speakers of English (and teachers) would accept the first sentence as correct, but heavy punctuators would perhaps insert a comma. However, QCA (communication following telephone inquiry) would not penalise non-use of the comma after the subordinate clause in ‘When he went back to his school his friends were amazed’. Perera (1984: 174) demonstrates how commas need to be used to avoid ambiguity in certain circumstances, but they are not obligatory in all cases as Grammar for Writing (DfEE, 2000: 104) might lead one to conclude. However, the second sentence (He heard stories going around …..) in the above example suffers as a result of poor punctuation. By turning the last two clauses into a sentence (full stop after happened) the text can be improved quite significantly. This writer’s problems are not brought about by discrete features of grammar such as agreement, tense inconsistencies or non-standard English forms like malformed negatives, but by failure to recognise where sentences are best divided. A further example from a 13-year old (Year 9) boy demonstrates the emergence of features associated with mature writing (for example, post-modification of the noun phrase, non-finite clauses and relative clauses) but the demarcation of clauses and sentences remains the challenge: The man with the brown coat rushed over to help Alan but he found Alan had been impaled on a group of sharp stick one of which was sticking through his neck, the man with the brown coat pulled Alans bike off Alan and tried to slow the bleeding coming from alans neck with his coat. Better use of commas, the full stop, the apostrophe and capital letters would significantly enhance the accuracy of the text. From the study of unrehearsed writing samples, some general trends could be identified, for example that: boys made more punctuation and spelling errors than girls but not significantly so; greater understanding of how to identify and demarcate the sentence might benefit a number of writers; girls appeared to be at higher NC levels (half a grade by Year 9); more girls used a variety of conjunctions (boys, 59%, girls, 78%), with 41% of boys relying heavily on ‘and’, (22% of girls). Course work or homework writing 7 Samples of writing were collected from 11 students across the ability range and subjected to analysis using the QCA coding frames (QCA, 1999b). As already explained, this type of writing was considered to be ‘rehearsed’ in some way, i.e. with time for planning. While content and expression were more developed in course work, course work writing at mid and low levels exhibited similar mechanical difficulties to those found in unrehearsed writing, for example: limited use of conjunctions, dependence on and, or and but, difficulties with the co-ordination of sentences (omission of relative pronouns), punctuation. In addition, it was found that punctuation and spelling difficulties in Years 8 and 9 occurred in the writing of Year 10 students (the subject of a separate analysis). Table 6: Clause Use in Rehearsed Writing Years 8 and 9 Yeargroup & gender Total clauses Real sentences Clearly punctuated Y8 Boys Y8 Girls Y9 Boys Y9 Girls Total 338 298 546 786 1968 182 106 199 289 776 143 76 178 239 636 (82%) Clauses coordinated with ‘and’ 36 57 41 63 197 Subordinate conjunction Non-finite clauses Relatives 69 84 158 264 575 47 38 68 71 224 15 12 43 53 123 Year 8 boys wrote fewer clauses per sentence than girls but this difference did not show between Year 9 boys and girls. Table 7: Clause Use in Rehearsed Writing Writing Yeargroup & gender Y8 Boys Y8 Girls Y9 Boys Y9 Girls Total Clause Use in Unrehearsed Total clauses Real sentences Clauses per sentence Total clauses Real sentences Clauses per sentence 338 298 546 786 1968 182 106 199 289 776 1.86 2.81 2.74 2.72 2.54 121 234 461 352 1168 70 96 191 153 510 1.72 2.44 2.41 2.3 2.3 Errors in Course- and home-work There were 548 identifiable sentence level errors in texts totalling 13134 words, an average of 24 words per error. Spelling errors were fewer in this type of writing, perhaps suggesting that greater planning time contributed to more accuracy. Grammar accounted for a larger percentage but still a minority (21%) and again very few errors were attributable to the influence of non-standard English. Table 8: Rehearsed writing Years 8 and 9: errors 8 Total errors Grammar Punctuation Apostrophe Capitals Spelling 548 116 208 47 45 116 Other: e.g. colloquialisms, cohesion, odd words 9 Punctuation in rehearsed writing There were 632 correctly demarcated sentences (81% accuracy, out of a possible 776 identifiable sentences) with clear full stops. Yet, even in this type of writing, omission and comma splicing were still a challenge for a number of students. Table 9: Punctuation errors in course work Appropriate full stops Omission of full stop Comma splice Intrusive full stops Omission of comma Omission of non-sentence initial capitals e.g. proper nouns, I, Inappropriate capitals e.g. as in daft as a Bat Year 8 (16 extracts) 219 33 38 8 15 16 Year 9 (18 extracts) 417 36 40 2 36 29 Again, the apostrophe was a stumbling block with 36 errors in total. Grammatical errors Syntactic errors were similar to those in unrehearsed writing, with 14 slips in relation to agreement e.g. there was rocks all over the place. A full list of grammatical errors can be found at Appendix 3. Nineteen of the grammatical errors relate to one particular student’s difficulty with reported and direct speech and this contributed significantly to the higher number of grammatical errors found in the rehearsed writing sample. Other errors could be ascribed to performance slips associated with first drafting e.g. the omission of words such as parts of verb chains as in: …he could back to his house … all of which could be improved through careful editing. Perera (1984: 22) reports that older children make more frequent use of modal auxiliaries, combinations of auxiliaries and catenative phrases e.g. I have decided to put together all the general facts. This seemed to be occurring in Year 9 course work and it could be the case that some of the errors occurred because students were grappling with more complicated syntax than that expected for the completion of the unrehearsed tasks. For instance, two students in this school had difficulty with the third conditional (see Appendix 3), for example: If you had … then it will If we had more time we should have measured It would have been better if we had a room with a steady temperature. If we had more time, we should have took 5 minutes. It would have been better if we did more samples Life would have been easier for Joseph Merrick if he was born (2) …. This problem occurred only eight times in scientific writing (the evaluation section of an account of an experiment) and in an English homework, but was not a cause for general concern, rather a sign of the emergence of more ambitious writing. Perera (1984: 229) suggests that this must be a late development even for assured writers as reported in the 9 samples of Burgess et al (1973) which showed similar difficulties for 13/14 year old writers. Clause length increases as writers mature and older students use more perfect tenses, progressive forms, more passives and more modals. They use fewer compound sentences and more complex sentences. Our investigation supported such claims. Non-standard English in homework and coursework was yet again not a significant factor but there were occasional colloquialisms: The main reason for this unjust way of treating these poor children is that there are far too many in comparison to the amount of workers there are to look after to them. Because there are too many children, some of them have to be gotten rid of in some way. In some cases, the difficulties that arose were of a particular nature that would need to be addressed on a one-to-one basis. A Year 9 boy wrote his prediction and evaluation section in science as follows: I think the higher the metal is on the reactivity scale will have the higher peek tempter because the more reaction the more the atom get unstable the more heat is produced for example magnesium is the highest metal I am use in the reactivity scale so I think will have the highest peek tempter then aluminium then zinc and then iron but I do not know about the aluminium I used was not pure. ‘I think the test I did on reactivity of metals was not all fair for I did not accumulated the mass/weight if the metal witch can change the out come of the result witch over all makes the test void.’ Spelling is relatively good, but some of his attempts were subject to phonological influence or confusion with a homophone e.g. tempter/witch. The content shows evidence of reflection but sentence co-ordination and punctuation are a challenge for this student (although there are signs that they are emerging). The impression is of waves of clauses, as a result of full stop omission. The analysis of students’ writing revealed that course work writing at mid and low levels exhibited a similar range of inaccuracies to those found in some of the less successful unrehearsed writing. These included difficulties such as the co-ordination of long sentences (sometimes resulting from limited use of relative pronouns) or the omission of full stops leading to writing in waves of clauses. While there were occasional grammatical errors and a few intrusions from non-standard English, these were much less frequent than inaccuracies in punctuation or spelling. In general, difficulties in spelling, punctuation and co-ordination affected boys slightly more than girls, but not significantly so. In addition, it was found that, although their frequency had diminished, some of the difficulties encountered in Year 8 work were found in the writing of those in Years 9 and 10. Writing-Related Findings from Questionnaires and Interviews Before concluding, some findings from our other investigations in the school about students’ writing habits provide a context for considering our recommendations. Analysis of students’ questionnaire responses revealed the following: more girls plan their writing (59%) than boys (38%); planning decreased with age, from 63% of age group at age 11(not whole year) to 38% at age 14, but planning levels among boys remained lower in each year; 56% of boys believe most teachers have explained how writing should be done in their subject and 48% of girls believe this; 10 boys appeared to be more confident, 38% saying that they had difficulty with the writing of a subject, compared to 57% of girls (was this due to lack of awareness?); girls took greater care and redraft more than boys when writing up in each year e.g. 84% to 63% in Year 9, 78% to 63% in Year 8; boys think they write as well as the girls (are the girls less confident or more realistic?); 72% of boys prefer computer writing, 55% of girls (63% overall). In individual interviews, students had difficulty recalling how they were taught writing in different subjects and several claimed that they did not really plan writing. While students were generally positive about school, there was a lack of awareness or at least vagueness about: a) the variety of writing they engage in across the curriculum; b) planning for writing; c) how they had been taught writing. As one teacher respondent claimed, far fewer boys (than girls) planned their writing. To what extent this is significant could not be determined, but given inaccuracies identified the following issues might be considered for further research, if we wish to focus on the accuracy of students’ writing: teaching of editing strategies (including punctuation, spelling, cohesion, coherence) students’ use of planning strategies time given to awareness raising about the different genres occurring in the curriculum the effectiveness of feedback to students about their writing. Little hostility was expressed towards writing, but there was limited enthusiasm (and the greater enthusiasm came from girls). Boys preferred factual writing to imaginative work and they appeared to read less widely. Conclusions The analysis of students’ writing suggests that a number of issues could be addressed across the curriculum to the benefit of both boys and girls, notably planning and editing strategies (including focusing on punctuation, spelling, cohesion, coherence). The analysis of errors yielded little evidence in support of a strong focus on features of grammar, the focus of many recent curriculum initiatives. The Literacy Progress Unit Sentences begins (DfEE, 2001) with units on the sentence, capital letters and then commas. However, if we wish to focus on securing greater accuracy, input on the use of commas and full stops could be justified as students progress through the levels of KS3, as this might assist a large number of pupils. Year 7 English 2002/03 Booster lessons (DfES, 2002) focus on paragraph formation (p45), connectives (throughout), but the focus on punctuation is delayed until lessons 12-14. Our study suggests that the priority given to grammar should be re-considered. In this regard, Literacy Across the Curriculum (DfES, 2001) may be a missed opportunity and the extent to which its focus was determined by what and how children write is not clear. It was certainly informed by QCA studies of difficulties and errors in students’ writing but to what extent does it allow for an exploration of the nature of children’s writing so that HOW students come to write is understood? To what extent do teachers know how punctuation develops, how spelling is acquired, how and when subordination or the use of non-finite clauses emerges in the written work of young people? In the light of our case study, we are unsure whether gloomy reports are justified. Our case study confirms the findings of previous work like the Technical Accuracy Project (QCA, 1999a) and other studies of young people’s writing (for example, Williamson and Hardman, 11 1997a). We found that there were differences between unrehearsed writing and homework/coursework, the latter being more accurate possibly because students have more time to engage in the writing process. Nevertheless, even in the unrehearsed writing, students wrote 75/80% of their sentences with accuracy; most words were correctly spelt (over 95%); grammar was generally accurate and non-Standard English intrusions were very infrequent. Possessive and omissive apostrophes caused difficulty to some students (though not all). Clearly, there are challenges, in particular punctuation and spelling, but what is needed is not a heavy emphasis on grammar, but an identification of interventions that can take us a stage further in addressing the difficulties that writers face in order to write with greater accuracy. References Alexander, J. and Currie, A. (1998) ‘I Normally Just Ramble On- Strategies to Improve Writing at Key Stage 3, English in Education, 32/2: 36-43 Allen, N. (2002) Too Much, Too Young? An Analysis of the Key Stage 3 National Literacy Strategy in Practice, English in Education, 36/1: 5-15 Allison, P. Beard, R. and Willcocks, J. (2002) Subordination in Children’s Writing, Language and Education, 16/2: 97-111 Beard, R. (2000) Developing writing 3-13, London : Hodder and Stoughton. Burgess, C. et al. (1973) Understanding children writing, Harmondsworth: Penguin DfEE (2000) Grammar for Writing, London: DfEE DfEE (2001) Literacy Across the Curriculum, London: DfEE DfEE (2001) Literacy Progress Unit: Sentences, London: DfEE DfEE (2001) Year 7 Sentence Level Bank, London: DfEE DfEE/QCA (1999) English: The National Curriculum for England, London: DfEE DfES, (2002) Year 7 Booster Lessons, English 2002/03, London: DfES HMI (2000) The teaching of Writing in Primary Schools: Could do better (a discussion paper by HMI), http://www.ofsted.gov.uk/publications/docs/957.pdf (accessed 10 September 2003) Nightingale, P. (1988) Understanding processes and problems in student writing, Studies in Higher Education, 13/3: 263-83 OfSTED (1999), The National Literacy Strategy: An evaluation of the first year of the National Literacy Strategy, London: OfSTED OfSTED (2002), The National Literacy Strategy: the first four years 1998-2002, London: Perera, K. (1984) Children’s writing and reading: analysing classroom language, Oxford: Basil Blackwell Qualifications and Curriculum Authority (QCA) (1999a) Improving Writing at Key Stages 3 and 4, London: QCA Qualifications and Curriculum Authority (QCA) (1999b) Technical accuracy in writing in GCSE English: methodology, London: QCA Qualifications and Curriculum Authority (QCA) (2001), Standards at Key Stage 3 English: A report for headteachers, heads of department, English teachers and assessment co-ordinators on the 2000 national curriculum assessments for 14-year olds, London: QCA Qualifications and Curriculum Authority (QCA) (2002), Standards at Key Stage 3 English: A report for headteachers, heads of department, English teachers and assessment co-ordinators on the 2001 national curriculum assessments for 14-year olds, London: QCA Williamson, J. and Hardman, F. (1997a) Those Terrible Marks of the Beast: Non-Standard Dialect and Children’s Writing, Language and Education, 11/4: 287-298 Williamson, J. and Hardman, F. (1997b) To Purify the dialect of the Tribe: Children’s Use of Non-Standard Dialect Grammar in Writing, Educational Studies, 23/2: 157-68 12 Appendix 1 Unrehearsed Writing Task Instructions We would like to collect some examples of your writing to help us to understand how you respond to school writing tasks. The writing will not be marked but will be analysed to see how it matches criteria expressed in the National Curriculum. It will not be read by your teachers. Your teacher will allow you about 20/25 minutes in total and you can write as much as you have time to write. Please put your name, age and form at the top of the paper and the number of the task you choose. You have a choice of task and you can do one or more of the following. 1. Read about the following situation and complete the story. Apart from a man with a brown coat, Alan was the only person on the field that day. The council lawn mowers had been there that morning so there were lines of dead grass all over the field. That’s why he rode straight into the brick under the dead grass. He lost his balance and went tumbling to the ground with his bike on top of him. …….. 2. Write about your future, beginning: Ten years from now, I’ll be ………………………………. 3. Write about your life at the present time, beginning: The most important thing in my life at the moment is ……………….. Thank you for doing your piece(s) of writing. 13 Appendix 2 Year 8 and 9 grammatical errors in unrehearsed writing Total number of words: 7424 Errors Verb Phrase Errors Number Examples The important things in my life is…. My hand grab … I meet him about three weeks ago Confusion of will/would Agreement 5 Tense of main verb Tense of modal verb 4 3 Non-standard past participle Omission of verb (slips) 6 8 Infinitive form Omission of –ing 1 2 Omitted apostrophe Intrusive apostrophe Phonological intrusion (homophones) Prepositional Phrases Omission Noun Phrase Determiner Omission Determiner a/an 19 2 4 Im not; dont work; thats He say’s; he come’s round Would of kicked; guess were; through (throw) 3 Out his arm; because the pain 3 7 Possessive determiner Possessive apostrophe Intrusive apostrophes 2 17 11 Number 4 With minimist look; when puppy A award; a incredibly clean flat; a interior designer; and friendly school He leg was checked; in the steps of him Mums cousin; the bikers ticking; childrens faces Cutting thing’s; lot’s of holiday’s; tube’s in his mouth; a mate of one of my mate’s No ones was there; family of the poor Total Had fell; was stood I training; It used and still has the potential to become … ..to opened …. Didn’t seem to be walk; doing what I like best, play football 101 14 Appendix 3 Grammatical errors in course and home work Errors Verb Phrase Errors Number Agreement 14 Tense of main verb 5 Tense of modal verb Conditionals 8 Non-standard past participle or past tense 8 Omission of verb (slips) Word order: Omission of –ing 4 1 3 Omitted apostrophe Intrusive apostrophe 10 4 Phonological intrusion (homophones) Prepositional Phrases Omission 4 Examples There was rocks all over the place. The numbers of people attending matches has increased; A family that have ….. The reason it undermine my prediction; 9 out of 12 children die because they were tied up Confusion of will/would If you had … then it will If we had more time we should have measured It would have been better if we had a room with a steady temperature. If we had more time, we should have took 5 minutes. It would have been better if we did more samples Life would have been easier for Joseph Merrick if he was born (2) …. We should have took; I could of weight it; When Colm first seen the duck (2); they lead (led) x 2; destructed; did not asked; It easy to grow; All she can is do not think …. I am use Its (3) for it’s; don’t; The writer make’s the reader; his wife see’s; she say’s; Lizzey’s awoke I could of (4) 2 Out the window; teams are centred large northern cities Noun Phrase Determiner Omission 2 Determiner a/an Intrusive pronouns 1 2 Pronominal reference 4 Possessive determiner Possessive apostrophe 3 16 Intrusive apostrophes 6 Omission 1 Negative 1 Number 5 A reason could be cost of tickets. This is enclave. And little town like Glossop Children who are near to dying they are put in there and left to die When arrests dropped from …… a year later, it rose…; They were all unhappy that he could not help him (reference unclear); The emergents …it … Says my wife (his) x 5 (see direct speech) Its (counted below) Worlds heroin trade; the egg was the wild ducks; fortune-tellers hut, Colms claims Parent’s wouldn’t …; Communist’s came to power; it’s contents (3); a few month’s More water in the test-tube than in the previous … The doctor said was lucky A family that have no home, anything to sell or any money. Every thirty second; many tall office apartment… Amount of people (2) Reported and direct Speech Total 19 (one student) 123 15 He was asked did he commit … Her response was yes I left at about …. …says my wife …. That/zero that Because When If So/so that As What D Speech How Until As …. As e.g.much, Where While Why Although As though/if After More than Before Like Even if/though The more ..the more Unless As soon as Who Such as How much/far Which Whether (if) In case In order to By + -ing Instead of Whilst –ing Appendix 4 Use of subordinating conjunctions Years 8 and 9 RE course or English work Science work Geography homework 4330 2867 work 693 5199 7 93 25 34 Unrehearsed writing 7424 34 Total 20513 193 3 1 1 1 0 3 4 1 0 1 14 32 16 12 15 13 10 5 4 2 10 5 10 12 5 0 0 2 2 3 37 16 8 19 9 4 0 1 4 0 24 28 18 7 16 18 15 6 2 7 88 82 53 51 45 38 29 15 12 12 0 3 2 0 0 0 2 0 0 1 8 3 3 1 4 3 0 0 2 0 0 1 2 0 0 0 1 0 1 2 2 0 0 3 0 1 2 1 0 0 1 2 1 5 3 2 0 3 1 1 11 9 8 8 7 6 5 4 4 4 0 0 2 1 0 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 2 2 2 2 2 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 6 1 0 0 11 6 1 0 21 1 1 1 14 3 0 0 12 0 0 0 64 11 2 1 Year 8 Year 9 Total Rehearsed writing 13 48 61 Year 8 Year 9 Subordinators 218 591 Sentence Initial Sub-ordinators With comma Unrehearsed 3 11 17 26 20 37 Initial position 24 (11%) 74 (12.5%) 16 With comma 4 (17%) 28 (38%) With comma 1 7 8