Acute purulent diseases of soft tissues: hydradenitis

advertisement

Lecture 11.

“Surgical infection. Classification. Acute purulent infection.

Osteomyelitis.”

The microorganisms divides on pathogenic and nonpathogenic, but this

division is conditional.

Pathogenicity of a parasite — it is it ability to call infection disease in

organism of the host. Pathogenicity of microorganisms dialectically is connected to

immunity of an macroorganism. Even the agents with expressed pathogenicity not

always can call disease. And on the contrary, at a significant drop of immunity of

an organism under influence of those or other conditions the disease develops at

the expense of a duplication of an agent, nonpathogenic for an organism with

normal immunity.

Modern hospital infection is called in basic just by these last biologicalecological groups of pathogens (nonpathogenic obligate and facultative parasites).

The purulent processes are called by various microorganisms but the most often

reason of their development are Staphylococci, Streptococci, Pneumococci,

Gonococci, Blue pus bacilli, Escherichias etc. Quite often agent of purulent

process happens a symbiosis of several aerobic microorganisms or even their

combination with anaerobic microorganisms. It’s mixed infection.

On clinical current and pathoanatomical to changes in tissues all kinds of

surgical infection are divided on acute and chronic. Acute surgical infection is

divided on acute purulent, acute anaerobic, acute specific – (tetanus, antrax) and

acute putrifactive.

The chronic surgical infection can be nonspecific and specific (tuberculosis,

actinomycosis etc.).

Classification of purulent surgical infection

1. On clinical current is distinguished acute purulent infection — general and local,

and also chronic purulent infection — general and local.

2. On localization of a defeat selects a defeats of a skin, underskin fat; covers of a

skull, its contents; neck, breast, chest wall; pleura, lungs, mediastinum, peritoneum

and organs of abdominal cavity; pelvis and its organs; bones and joints.

3. On aetiology purulent surgical diseases are Staphylococcus, Streptococcus,

Pneumococcus, etc.

4. On aetiology distinguishes also purulent mono- and polyinfection.

SPREAD OF INFECTION

Cellulitis

Cellulitis is inflammation spreading along the subcutaneous or a fascial

plane often as the result of infection with Streptcoccus pyogenes which has entered

the tissue through an accidental wound, graze, or scratch, or following surgical

incision. Unchecked this may lead to septicaemia after a rapid spread within the

tissues. Initially red and itchy at the site of the innoculation, the skin swells and

becomes tender, frequently being shiny. There may be local gangrene. Rest,

elevation of the part, and the appropriate antibiotic should lead to resolution, but

any underlying condition (e.g. diabetes) should be treated.

LOCALLY—Celtulitis

INFECTION

REGIONALLY—Lymphangitis

SPREADS

Lymphadenitis

GENERALLY (systemically)

BLOODSTREAM—Bacteraemia

Septicaemia

TO OTHER

BODY CAVITIES—Peritonitis

PATIENTS

Meningitis

—LYMPHATIC SYSTEM

Cellulitis in special sites

Orbit.—Spreading infection from wounds of the paranasal sinuses will cause

proptosis and impairment of ocular movements. Associated thrombophlebitis can

extend to the meninges and, if the ophthalmic veins are involved, to the cavernous

sinus. Early attention and the use of antibiotics (Penicillin) is vital in reducing

morbidity.

Neck.—Submaxillary cellulitis is often termed 'Ludwig's angina" and the great risk

of infection spreading from tonsils or mastoids to the neck is that the cellulitis will

involve the glottis with concomitant oedema, asphyxia and mediastinitis.

Pelvic cellular inflammation.—The common cause is a lateral tear in the cervix

during parturition. The pelvic inflammation as a result of the trauma incurred

during childbirth may extend along the broad ligament appearing above the

inguinal ligament. Anaerobic infection (actinomycosis) and Chlamydial infection

may arise as secondary infections following the use of intra-uterine contraceptive

devices. They will present as a cause of pelvic pain and the diagnosis requires the

culture of endocervical pus. Metronidazole should be used whilst awaiting the

results of cultures which should also exclude sexually transmitted infections (N.

gonorrhoea or herpes virus infection).

Localised infection will spread by lymphangitis to local or regional lymph nodes

and by bacteraemia to distant organs.

Bacteraemia and Septicaemia (overwhelming bacterial proliferation and toxins in

the blood).—These terms describe the presence of organisms in the blood. The

clinical features include a source of infection, hypotension, pyrexia and often

rigors ('shaking of the bed'). Hepatic involvement and acute cortical necrosis of the

kidneys may be associated with bacteraemia, also peripheral circulatory collapse.

Intra vascular coagulation defects frequently accompany the later stages.

Following at least three blood cultures treatment must be immediate and

aggressive by means of a broad spectrum attack using a p-lactam antibiotic

together with an aminoglycoside and metronidazole, (these should be given

intravenously), with blood transfusions, plasma expanders and hydrocortisone.

Bacteraemia can cause multiple metastatic abscesses in distant organs and these

will require treatment.

Abscess Formation

An abscess is a collection of pus. Bacteria which cause pus (pyogenic bacteria)

reach the infected area by:

(1) Direct infection from without, e.g. penetrating wounds.

(2) Local extension from some adjacent focus of infection.

(3) Lymphatics.

(4) Blood-stream (haematogenous).

Pus is a collection of polymorphonuclear leucocytes from which the

proteolytic enzyme causes liquefaction of the tissues. The tension within an

abscess rises as plasma exudes into it and, unless the abscess is surgically drained,

the pus will discharge eventually along the line of least resistance. The area

immediately around the abscess which is infiltrated with leucocytes and bacteria is

called the pyogenic membrane.

Symptoms depend upon the site, size and tension of the abscess and the virulence

of the bacteria causing it; the patient will suffer generalised illness, and throbbing

pain with swelling.

Signs of Pus—

(a) GENERAL.—The temperature is elevated and bacteraemia with rigors may

occur.

(b) LOCAL.—The five classical local signs of inflammation are due to hyperaemia

and inflammatory exudate : 1. Heat. 2. Redness of the skin over the inflamed area.

3. Tenderness. 4. Swelling. 5.Loss of function.

Prevention.—An abscess can usually be prevented by timely and appropriate

antibiotic treatment.

Treatment. Once pus is diagnosed, the abscess must be incised and dependent

drainage instituted as penetration by antibiotics is poor. In 'high risk' anatomical

areas, as in the neck or axilla, Hilton's method should be used. This consists of

incising the skin and superficial fascia, and opening the abscess by thrusting a pair

of sinus forceps or a haemostat into the cavity. By separating the blades, a

sufficiently large opening can be made to insert, if necessary, a finger in order to

convert loculi into a single cavity, and to insert a drainage tube. Pus should be

cultured in order to isolate and identify the organism and its sensitivity to

antibiotics. The underlying cause needs to be ascertained and appropriate treatment, e.g. surgery, instituted.

Errors in treatment.—If pus is not drained and antibiotics are continued, the

inflammation continues to smoulder and a hard lump forms, called an 'antibioma'.

In certain areas, e.g. the breast, it becomes difficult clinically to decide whether

such a lump is malignant or inflammatory.

Incising an aneurysm in mistake for an abscess. It has been done on many

occasions

IMAGING IN INFECTION

There are four available techniques which allow surgical infections and collections

of pus to be accurately diagnosed and clearly defined:— Conventional radiology,

Isotope scanning. Ultrasound (US), Computed Axial Tomography, (CT). The

clinical indications will usually determine the appropriate technique and the site of

infection will influence the choice of investigation.

Conventional radiology, for example, reveals fluid levels when air or gas is present

as in subphrenic abscess or lung abscess, or pus suggested by an opacity filling a

space (the nasal antrum or the pleural cavity).

Isotope scanning.—Intravenous technetium accumulates at the site of infection and

clearly demonstrates the position of brain abscesses, inflammation such as

osteomyelitis, and hepatic abscesses. Gallium scans may be needed for mediastinal

abscesses, pelvic and perinephric abscesses or subphrenic abscesses, but care in the

interpretation is needed as gallium is taken up by normal breast tissue under certain

circumstances. Ultrasound or CT scans of suspicious areas may show regular

necrotic centres which will help to distinguish abscesses from tumours.

Ultrasound (US) reliability depends upon close contact of the US probe and the

skin. It cannot be used over surgical wounds, colostomy or ileostomy bags. Gas in

the bowel obscures the underlying organs and therefore US is of the greatest use in

liver, spleen and urinary bladder investigations whilst it is of considerable value in

the diagnosis of gallbladder stones or empyema. The demonstration of bacterial

vegetations upon a cardiac valve by echocardiography can be decisively diagnostic

of endocarditis.

Computed tomography (CT) scans are usually necessary for localising brain

lesions and abscesses although isotope scans can demonstrate these also.

PREVENTING INFECTION

Antibiotic Prophylaxis is used to prevent bacteraemia and wound infection when

instrumentation or surgery is performed upon a site with normal flora or where

infection already exists (e.g. cystoscopy when bladder infection is known to be

present). It should be maintained for a short period, seldom using more than three

doses, the maximum duration being 48 hours. Prophylaxis should cover and

control the known or likely pathogens. Prophylaxis may conveniently be given

intravenously as a bolus after induction of anaesthesia or, ifintramuscular

antibiotics are to be used, may be given one hour before surgery. Aminoglycosides

such as gentamicin require that serum levels be monitored if they are used for more

than 36 hours. If renal function is known to be satisfactory three doses only of 80120 mg given at 8 hour intervals may be used for a normal adult.

Metronidazole may be given as one gram per rectum (suppository) with resulting

excellent blood levels; the first suppository should be given 1 1/2 hours

preoperatively. Topical antibiotics should be reserved for use in eye or ear surgery;

skin antibiotics are seldom if ever indicated and can lead to severe antibiotic

resistant infections.

Antibiotic impregnated 'cement' or 'beads' for use in orthopaedic prosthetic

operations are gaining favour; they act as a local reservoir giving slow release to

the site of operation. Alternative regimes are based on single doses of

cephalosporins, e.g. prior to the open reduction of fractures.

Care should be taken with diabetics (superadded Candida and multi-resistant

Gram-negative infections) and patients who are immunodeficient or

immunesuppressed, e.g. receiving steroid therapy or receiving radiotherapy.

Penicillin prophylaxis for up to one week is mandatory for the prevention of

Clostridial gas gangrene at the time of lower limb amputation through the thigh in

those patients who have diabetic or severe peripheral vascular disease.

PREVENTING INFECTION IN SURGICAL PROCEDURES

Abdominal procedures Colorectal surgery

Ampicillin 500 mg I.V. 8

hourly x 3* + Metronidazole

Appendicectomy

Metronidaxole i gram rectally

Peritonitis

Ampicillin 500 mg

Gentamicin 120 mg followed by

80 mg twice at 8 hour intervals

with Metronidazole

Biliary

Ampicillin or a cephalosporin

Urinary tract

Amoxycillin 3 g or single dose of

Instrumentation or

Gentamicin 120 mg if previously

surgery

infected

Obstetric surgery

Vaginal hysterectomy,

Ampicillin 500 mg I.M.

termination of pregnancy

Metronidazole I g rectally

with history of pelvic

once only

inflammatory disease

or abdominal caesarean

Orthopaedic

Compound fractures

Ampicillin 500 mg 8 hourly with

Flucloxacillin 500 mg 6 hourly

(or Erythromycin 500 mg 6 hourly

if Penicillin hypersensitive)

Elective or prosthetic 48 hours only Ampicillin 500 mg

8 hourly surgery

and Flucloxacillin 500 mg 8

hourly

Lower limb amputation Penicillin 2 mega units at

induction and thereafter 4 mega

units daily for 5-7 days

Patients with known

1. Dental surgery

Amoxycillin 3 g orally and

valvular disease,

Probenecid I g, orally (if allergic

prosthetic grafts of the 2. Urethral

to Penicillin, Erythromycin 1-5 g

cardio-vascular system catheterisation orally followed by 0-5 g 6 hours later).

(e.g. aortic or aortic

3. Operations under

If general anaesthesia or

valve), history of

general anaesthesia

gastrointestinal investigation is

rheumatic fever

being performed a single dose

of Gentamicin 1-5 mg per kg of

body weight I.M. must be

added

Preventing Infection at Operation.—The open wound is at risk of contamination

from airborne dust which carries bacteria derived from skin organisms of

attendants and operating room personnel. Positive pressure, filtered ventilation of

the operating theatre prevents bacteria gaining entry with the air. Ultra-clean

ventilation (laminar flow and fine filters) has been shown to reduce wound

infection rate by two-fold. Body exhaust suits carrying away the infected skin

particles of the surgeons and assistants clearly reduces the number of infected

particles near the wound and has been shown to reduce the wound infection rate by

sevenfold.

The patients own skin is a source of infection especially at abdominal operations

and can be treated by pre-operative bathing, and skin preparation with alcoholic

povidone iodine solution or 5% chlorhexidine in 70% alcohol. Povidone iodine

compresses applied to the thigh for one hour prior to hip arthroplasty reduce the

risk of self infection. At the time of operation, the use of a plastic adhesive film

(Opsite®) through which the incision is made helps to prevent contamination

during the operation itself. Surgical hand washing with hexachlorophane,

chlorhexidine, or povidone iodine and the use of gloves, mask and change of

clothes all contribute to reducing the risk of surgeon transmitted infection.

Instruments.—Central hospital and theatre sterile supply departments use high

temperature autoclaves (i32°C) for sterilising instruments, whilst equipment made

of heat sensitive material may be sterilised at 8o°C in sub-atmospheric pressures

('low temperature steam') with or without a formalin injection cycle (e.g. for

cystoscopes). Some endoscopes (e.g. colonoscopes) may require special

procedures for disinfection; liquid gluteraldehyde is often useful for disinfection of

cleaned instruments. Where viral infections (Hepatitis B) are implicated

hypochlorites or steam disinfection are used while in operating theatres the

infection control policy will clearly lay down guidelines for the disinfection of

blood contaminated instruments before cleaning if possible. The exercise of proper

professional care will usually prevent self-inflicted injuries with instruments that

may be at risk of spreading Hepatitis B virus or HIV virus by blood contamination.

Controlling Surgical Infection—Control of Infection Team.—Vigilance,

education and definition of policies for controlling infection in surgical wards is

best placed in the hands of a Control of Infection team consisting of a control of

infection nurse or considerable seniority, a medical microbiologist and a surgeon.

Not only is it necessary to monitor the type of infections and the resistance and

distribution of the bacteria, but the in-service education on the principles of wound

care, catheter toilet, aseptic dressing techniques can best be managed by such a

team. Isolation of high risk patients, modification of antibiotic regimes, and the

prevention of spread of any resistant infections will all require the combined

speciality interest for the advice to be authoritative, acceptable and effective.

Though the tissues do not react to each of the pyogenic bacteria in an exactly

similar way, the typical local effect of pyogenic infection is the formation of a

cavity filled with pus—an abscess—and the general or constitutional effect is the

establishment of fever, leucocytosis and prostration. The constitutional reaction

varies little in kind, though much in degree, whatever the pyogenic microorganism.

The character of the local reaction, on the other hand, is more directly related to

the type of invading bacterium. Frank suppuration, that is, a rapid solution of tissue

and a free outpouring of leucocytes, is habitually excited by staphylococci; and a

diffuse suppurative inflammation, cellulitis or phlegmon, characterized rather by

edema and necrosis than by an abundant formation of pus, is typical of

streptococcal infection. It is the frankly suppurative type of inflammation caused

by the familiar staphylococci of the skin which commonly gives rise to abscess.

The local signs of any suppurative inflammation are heat, redness, swelling

and pain, with which must be included sensitiveness to touch or movement, that is,

tenderness. Moreover, abscesses of sufficient size exhibit, to the practised touch,

fluctuation, a wave-like impulse transmitted through a soft-walled sac of fluid in

response to pressure. The combination of these various signs is unmistakable, but

since any one or more of them may for various reasons be absent, the significance

of each requires investigation. Difficult as it is to assign a relative order to their

importance, pain, heat and fluctuation appear to be of the greatest clinical

significance; redness of the least. They will therefore be considered in that order.

Pain results from the stimulation of sensitive nerve fibers or their endings and may

perhaps be attributed to distension by toxic substances of tissue supplied with such

fibers. The skin is well furnished with sensory nerves; the subcutaneous tissues and

muscles arc not. The periosteum, the serosa of points, the anterior rectus sheath,

the parietal peritoneum and the pleura are potential sources of exquisite pain, but

the abdominal and thoracic viscera are themselves comparatively insensitive,

though when distended by suppuration within, such solid organs as the liver,

spleen, and kidneys may become the seat of pain which must then be attributed to

the rapid stretching of their capsules and, in some instances, tension upon their

(parietal) peritoneal attachments.

The severity of pain is usually proportional to the rapidity in development of the

suppurative process. Thus an abscess which gathers slowly and distends the tissues

gradually, occasions comparatively little subjective sensation while a very active

process may be a source of agony. To some degree also the severity of pain is

influenced by the toughness of the tissue in which the abscess develops. For such

reasons, the minute infection (Paronychia) beneath the edge of the nail is painful

out of all proportion to its extent, and the same is even more true of acute

inflammation within the tough pulp of the finger tip (Felon). Subperiosteal

inflammation, particularly in regions where fibrous tissue is solidly attached to

rough bone, is notably painful. Perhaps the most agonizing of all are the abscesses

within the thick walls of the long bones (Osteomyelitis). On the other hand,

suppuration within yielding tissues may be almost unnoticed until, perhaps, it

reaches and invades one of the sensitive surfaces already mentioned.

Pain, then, is usually the most enlightening of all the symptoms of abscess. It

is increased by pressure or movement. Its character, even in the absence of other

local signs, may suggest the existence of an abscess and indicate its exact position.

The throbbing pain of a felon and the deep agonizing pain of acute osteomyelitis

are examples of this sort. On the surface of the body, pain is a less constant

evidence of abscess than heat, redness and fluctuation, since tension of the

inflamed sensitive skin is readily relieved by softening of the tissues and by even

partial evacuation. Abscesses in the skin are more sore than painful, though they

are often exquisitely tender to the touch.

Heat is due to local hyperemia but may be detected in the absence of any redness

whatever. In infections of the skin, the two signs go together, but beneath the

surface, the hyperemia about an abscess may be evident to the touch when the skin

is quite normal in color. Local heat is a very early and constant sign of even a

relatively deep suppurative process It is to be sought by comparing the suspected

region with a remote symmetrical part. In the presence of an abscess deep in the

thigh, or even within the femur, the surface of the affected leg may be ever so

slightly warmer than that of the other. The two thighs, in that case, or it may be the

hands or arms in another, should be lightly and simultaneously touched by the

sensitive palmar surfaces of the examiner's two hands, and the warmth of the

opposite sides rapidly compared. Local heat and pain are almost pathognomonic of

abscess, even though the suppuration is so situated that fluctuation can not be

elicited, and in the presence of superficial, fluctuating collections of fluid, absence

of heat distinguishes cysts and cold (tuberculous) abscesses from acute pyogenic

infections.

Fluctuation is a rather gross evidence of abscess. Since it merely points to the

presence of the collection of fluid, it’s only valuable when some other sign of

suppuration is detectable. Indeed it is chiefly an aid in confirming other findings

and in marking, for purposes of treatment, the exact position of the lesion.

Recognition of the fluctuant border of a collaction of pus may call attention to the

point at which dependent drainage must be established. Even a collection of fluid

too small to transmit an actual fluid wave may be detected in the midst of a

considerable brawny induration as a crater-like area of softening, and so indicate

beginning suppuration and a favorable location for drainage. Ordinarily, the sense

of fluctuation is sought by placing the palmar surface of the fingers of each hand

on the opposite sides of a swelling, or at a distance from each other upon a flat

surface, when, upon pressing down with one hand, the impression of a fluid wave

is received by the other.

Swelling would appear at first sight to be an indispensable sign of abscess. Indeed

it is usually present, and is quite apparent in such suppurations as are near the

surface of the body as well as in deeper ones of any notable size. In some

instances, however, tissues are destroyed and pus collects without causing any

appreciable swelling. In others, the abscess occurs in unyielding tissues or in

deeply seated organs concealed from sight and touch. Again, so many other

processes—new growths and cysts—are responsible for tumor that other signs of

suppurative inflammation are more reliable.

Redness, or hyperemia, is a very constant part of the response of the tissues to

irritation and is almost invariably present about an abscess. It is only noticeable,

however, when the abscess is near the surface. Then it is the earliest sign of

inflammation and precedes actual suppuration. But deeper abscesses may be

betrayed by the heat of hyperemia before any superficial redness is visible. This is

particularly true of infected operative or accidental wounds of considerable depth,

which may appear on the surface to have healed in a very reactionless way.

The Constitutional Symptoms of abscess become increasingly valuable and

even indispensable to diagnosis when suppuration is remote and inaccessible. A

painful, hot, red, swollen and fluctuant area would be recognized as an abscess

even without the confirmation offered by fever and leucocytosis, but deeply seated

pain, slight local tenderness upon deep pressure, and questionable local heat are

only suggestive of suppuration unless constitutional symptoms are present. In most

instances, the character of these general manifestations can be relied upon

implicitly; it is only in quantity that they vary. Since fever and leucocytosis result

from the reaction of the body to bacterial toxins, the virulence of the toxins is a

prime factor in this response. Naturally, the factor of virulence is influenced by the

degree to which toxic substances are absorbed into the general circulation, that is,

by the nature of the tissue in which the abscess originates. In these respects, the

richness of the blood and lymph supply in any region is a most important

consideration. The tension under which pus is retained is another. Thus a

suppurative process pent up in the vascular but unyielding medullary cavity of a

long bone promptly causes high fever, leucocytosis, and prostration, but an abscess

in the soft, yielding brain, which possesses almost no power of absorption, may for

a long time occasion no constitutional symptoms whatever. An infection within the

palm of the hand is a more potent source of fever than a similar process in the

loose, avascular fat of the thigh or the abdominal wall. Differences of this sort are,

however, matters of degree only. It almost never happens that an abscess of any

consequence fails to cause some rise of temperature, though instances of failure of

leucocytosis in the presence of overwhelming infection are not very rare.

Furuncle. A furuncle, or boil, is a very familiar form of abscess, peculiar to

the skin, and caused almost invariably by the staphylococcus aureus (or albus).

Infection reaches the dermis by way of a hair follicle or sebaceous gland. Bacteria

multiply rapidly at the point of entrance and here their toxins are sufficiently

deadly to provoke, before the protective defenses of the body can be set up, a rapid

necrosis of tissue. This slough is of such tough material as to resist for a time

complete solution. It remains, therefore, as the core of the furuncle. About it,

liquefaction of tissue and outpouring of a highly purulent exudate make pus, and

thus an abscess is formed in and beneath the true skin. About the abscess, new

vessels and young connective tissue keep the infected area surrounded by a layer

of granulation, to which the name pyogenic membrane is given. If the cocci

continue to develop, the pyogenic membrane is dissolved and the furuncle

enlarges. New defenses, however, again are built around it. Should the process be

prolonged, lymphoid and plasma cells begin to replace the polynuclear leucocyte.

Eventually, the invading bacteria are robbed of their virulence or the contents of

the abscess are evacuated, After incision or natural rupture, the cavity closes,

partly by collapse and partly by ingrowth of new tissue. Finally, a scar covered by

epithelium is left.

If the furuncle is observed from its beginning, it will usually be noted that a pustule

first appears about the base of a hair. In a few hours, a circumscribed dark red

swelling surrounds it. Heat, redness and pain are evident. The swelling slowly

increases until, from the fifth to the seventh day, a yellow, softened area appears at

its apex. The furuncle is then said to "point" and there is formed the beginning of

an opening from the abscess to the surface. Under favorable conditions, this

opening enlarges, so that there may be discharged through it by pressure the

sloughing "core" and pus. Sometimes the pus burrows beneath the upper layers of

the epidermis, making a flat, blister-like pustule. This communicates by a narrow

neck with the larger collection beneath. Such a furuncle has, on cross section, the

shape of a collar-button, a name which is often given to it, and the importance of

recognizing the lesion lies in this, that adequately to evacuate the deep portion of

the pus sac something more than the mere exposure of the superficial pocket is

required, ihe tiny opening into the deep pocket must be discovered and enlarged by

incision. From the time the furuncle is evacuated, healing begins. The discharge,

at first purulent, soon becomes serous and then drys up. Skin grows over the

granulations which fill the cavity. The resulting scar is often invisible.

One furuncle may lead to the appearance of many, suggesting, as indeed may be

the case, that a "crop" has been sown by the outpouring upon the skin of countless

virulent bacteria which have escaped from the original lesion. But of course the

same result may arise from a loss of resistance to a particular bacterium widely

distributed in the skin and heretofore held in subjection. The back of the neck is

commonly the seat of this sort of process; the axillary skin is sometimes most

stubbornly infected, the face is often invaded and the buttocks as well. Indeed, any

part of the skin may be affected. When the furuncles are in considerable numbers,

recurrent and spreading, the condition is known as furunculosis. Then the body

appears to have lost, to a greater or less degree, its combative quality. Under these

circumstances, a constitutional reaction in the form of moderate fever may be

present, and instances of considerable debilitation, doubtless partly due to the

annoyance and constant discomfort of the newly developing lesions, are sometimes

observed. That furuncles have long been considered a serious affliction may be

judged from the passage in the Bible wherein it is stated that "Satan went forth

from the presence of the Lord, and smote Job with sore boils from the sole of his

foot unto his crown," the most terrible affliction of which the devil could think,

and one which was intended to try Job's fortitude to the utmost. It is clear in some

instances and quite probable in many others, that furuncles afford entrance for the

staphylococci which so frequently occasion acute infections of bone in children.

Blood-borne staphylococcal infections of a similar source in persons of any age

may invade the lungs, kidneys, and other organs, not infrequently leading to a fatal

outcome.

Treatment: The furuncle should be evacuated in such a way as to render unlikely a

spread of infection into deeper tissues or into neighboring hair follicles. Thus it is

unusual to incise a boil before it has become a pus sac about which a well

organized pyogenic membrane is presumed to exist. And it is unusual even then to

incise until continued enlargement and absence of a necrotic spot upon its surface

indicate that it can not be ruptured by very gentle pressure. After opening, the

furuncle is covered with a sterile absorbent dressing. Sometimes a little piece of

guttapercha tissue is passed into it as a drain. Before evacuation, the skin about it is

kept as clean as possible with soap and water, and is often greased with a bland

ointment to keep the bacteria, as they are discharged from the opened abscess,

from finding new lodgment. A boil may sometimes be aborted by the use of hot

applications or the injection of a drop of pure carbolic acid into its core. The

application of heat, by increasing active hyperemia, hurries on the process to the

destruction of the bacteria or to frank suppuration.

When multiple active furuncles are present, the condition presents considerable

difficulty in treatment. The patient seems at times to lose all resistance and may

develop serious secondary infections. Under these circumstances, vaccines are

sometimes employed and may be useful. Many internal remedies have been tried.

The administration of yeast has sometimes seemed to do good. The salts of tin are

favored by a number of French investigators. On the whole, more reliance is to be

placed on general hygienic measures, in persistence in the most painstaking care of

the skin and in preventing the spread of sepsis from established furuncles to new

regions.

Carbuncle is a suppurative inflammation of the skin and subcutaneous tissue

having the form of a many headed furuncle, and like it, is caused by the

staphylococci. Its peculiar pathologic features and clinical course are due to the

nature of the tissue—the skin of the back of the neck, the back, the hairy dorsal

surface of the hand and fingers, and rarely the upper lip and scalp—in which it

originates. In these regions, the skin is particularly thick and tough, and from the

base of the hair follicles clefts of the true skin filled with fat—the columnae

adiposae of Warren—extend downward for a considerable distance. At their base,

these columns are firmly bound to the underlying fascia. Thus an infection which

does not rapidly reach the surface is likely to follow the fibrous attachments of the

columns downward to the deep fascia, whence it rises again to the skin through

other columns. The process once begun, spreads rapidly by the customary solution

of tissue and pus formation, reaching out continually along the deep fascia and

mounting in new areas. A rather terrifying lesion often several inches in diameter

may result. In its early stages, the carbuncle appears as a raised red area in whose

center pustules are dotted like the holes of a pepper pot. As it extends, its oldest

portion becomes a pussy grayish crater about which cyanotic skin, more tenacious

of life than the deeper tissues, forms an irregularly indented border. Large and

small openings and areas of slough surround the central crater, but in the newer,

growing area the early appearance of yellow pustules scattered or grouped in a

field of angry red is preserved and continued. Still beyond this zone is a region of

brawny edema diminishing in hardness and depth as the normal skin is

approached. The whole back of the neck and head from ear to ear may be occupied

by such a lesion.

Pain and tenderness are variable. Some carbuncles cause great suffering, while

others are painless and remarkably insensitive. When the lesion occupies the back

of the neck, the head is held rigidly bent forward. The patient is often prostrated,

sometimes delirious, and since carbuncles are particularly apt to attack diabetics,

the outcome is occasionally fatal. The small carbuncles which occur on the ulnar

side of the dorsal surface of the hand and upon the back of the proximal phalanges

of the fingers are misleading in appearance, since the many headed appearance of

the typical lesion is sometimes lost. Nor is it always realized that carbuncles occur

in these regions. Nevertheless they are exactly similar to the lesions of larger size

in other localities. Carbuncles of the face and scalp have a remarkable tendency to

invade the venous blood stream, leading to septic processes in the cerebral sinuses

and in the lungs.

Treatment will depend somewhat upon the general condition of the patient.

Careful physical examination with reference to chronic disease of the heart, lungs

or kidneys, and especially, examination of the urine for sugar, should always be

made. If the patient is profoundly septic and the carbuncle is not too large, the

whole may be excised by a circular incision carried down to the deep fascia. This

ends the disease more certainly, perhaps, than the less radical operations of crossed

incisions through the center of the carbuncle, the turning up of the flaps along the

plane of the deep fascia to the outer limit of the suppurative process, and the wide

open packing of the cavity which is usually employed. The anesthesia, should be

as innocuous as possible. Exposure to the x-ray, especially in the earlier stages, is

often curative, least so, unfortunately in diabetics. The carbuncle may soften early

or be "aborted." The sulfonamides and penicillin have been found effective,

particularly if infection is already present in the blood stream.

DIFFUSE SUPPURATIVE INFLAMMATION

This is a common, often severe and occasionally fatal disease. The names,

Phlegmon and Diffuse Cellulitis, are given to those suppurative inflammations in

which necrosis of tissue шау be extensive but pus formation is little marked;

in which the inflammatory reaction is rather in the form of intense widespread

vascularity and outpouring of serum than of local abscess formation; and in which

the streptococcus pyogenes is the usual infectious agent. Lymphangitis is the name

applied to an infection of similar origin confined to lymphatic channels. This may

occur as an independent process or may appear as an extension away from a parent

cellulitis. Almost invariably the superficial lymph vessels are the ones affected.

PHLEGMON, OR DIFFUSE CELLULITIS

Infection reaches the subcutaneous tissues by way of an injury which may be so

small and apparently harmless as to have been unnoticed. Or it may spread from

one of the common punctured, incised wounds of the fingers and toes. It is a

frequent cause, as will appear later, of septic hand. The organism —almost

invariably the streptococcus—causes a local necrosis with exudation. If the

infection is very mild, the exudate is soon absorbed and little loss of substance

occurs. If it is severe, destruction is extensive. When at last it has subsided, much

necrotic tissue remains to be cast off and the area occupied by the septic process is

largely converted into granulation tissue. As the resulting scar contracts, the

overlying skin is likely to become adherent to underlying structures. This sequence

of destruction, induration and shrinkage may impair the function of adjacent

muscle or tendon.

The appearance of such a lesion differs decidedly from that of a furuncle or

carbuncle. Redness and swelling appear about the point of origin. The skin pits on

pressure. The area of infection may extend up a limb or over the body, as the case

may be. Near the starting point of the process, the skin is a deep angry red. At its

advancing edge, which seldom is sharply defined, it is of a lighter color. Everywhere the inflamed tissue has, to the touch, a brawny feeling obscuring all

landmarks. In the older portion of the lesion an area of fluctuation or of crater-like

softening indicates the situation of advanced necrosis and the presence of a

collection of thin pus. Blebs, and even great blisters containing a cloudy fluid,

mark a particularly severe process, as if the tissues had been slightly burned.

Extensive destruction of skin (sloughing) may expose raw skin and a thick, yellow,

gelatinous subcutaneous layer from which a thin, cloudy fluid exudes in

abundance. And if, as resolution of the exudate occurs, such an incision is carefully

observed, it will be noted that larger and smaller bits of grayish tissue are

continually coming from the wound. In the most severe infections, this sloughing

is of great extent, involving large sheets of subcutaneous tissue and more or less of

the skin itself.

THE TREATMENT OF DIFFUSE SUPPURATIVE INFLAMMATION

The General Principles of Treating Established Diffuse Suppurative

Inflammation.—Since the discovery that hemolytic streptococci are susceptible to

the action of sulfanilamide, various other sulfonamides have been found to have a

similar action, some being superior to sulfanilamide in their effect upon certain

bacteria. All tend to sterilize the blood stream, having a bacteriostatic effect on the

organisms, but they do not kill the bacteria in the initial lesion which still requires

surgical drainage. Identification of the causal organism is therefore more than ever

necessary. The sulfonamides are given by mouth (the initial dose often

intravenously) but when sterilized, can be powdered freely into open wounds,

where, especially in fresh ones, they help to overcome infection, without

interfering with healing. For established infection they—and penicillin—are

unpredictably effective.

An example of one of the most familiar types of diffuse cellulitis is an infection

spreading from the tip of the elbow: a small contused wound may have been the

starting point. In the course of a few days the disease will have spread up and

down the arm, perhaps encircling it. Over the olecranon the skin may exhibit a

very small area of necrosis. For several inches in every direction, it will be deep

red and shiny. Swelling will be very great and of a porky firmness. The advancing

borders will show a fainter color and softer edema shading imperceptibly into the

normal tissues. No fluctuation will be discernible, but careful palpation may

disclose a softened area in the center and perhaps other crater-like spots about it.

Tender lymph nodes will probably be palpable in the axilla. Such a lesion can not

possibly be drained in the ordinary sense. Yet if the areas of softening are incised,

a considerable amount of thin pus will escape and perhaps small pieces of

sloughing fascia. Twenty-four hours of immobilization, elevation and hot

poulticing (which here finds its greatest usefulness) will show a marked

improvement. The skin will everywhere be wrinkled, a sure evidence of receding

edema, the redness will have decreased, the lymph nodes in the axilla will have

subsided, and if a blunt instrument is passed into one of the incisions, it will

probably be found that new pockets have become connected with the original

openings. More exactly dependent drainage may then be indicated. The speed of

recovery will depend upon the amount of dead tissue which must be cast off or

absorbed, and upon the persistence of the organisms in scattered areas.

Phlegmonous processes in certain regions, as in the case of the hand or foot, may

penetrate into complicated tissue spaces or tendon sheaths. They may also become

a starting point for lymphangitis. The treatment of this latter condition requires the

nicest judgment, for though it is not of itself a suppurative condition, yet too often

it leads infection to regions which may require drainage. A small area of infection

about the hair follicles on the back of one of the fingers may, without warning,

occasion a sudden extension of lymphangitis which winds up the back of the hand

and arm to the axilla. Chills, high fever, and intense prostration may be present. In

such a case, incision of the long streak or streaks of lymphangitis would certainly

spread rather than restrain infection. Incision of the primary focus might and

probably would be beneficial, but immobilization, elevation and poulticing will

usually (certainly at the beginning) be more helpful. In all probability, there will be

no breaking down of tissue, and unless the infection is of such virulence that death

follows within twenty-four hours, the whole process will probably subside in a few

days, leaving no trace. Indeed, any operative treatment which it requires is called

for only by the lesions with which it is associated or by the complications it causes.

Mastitis of infants is at least as common in the male as in the female. On the

third or fourth day of life, if a breast of an infant is pressed lightly, a drop of

colourless fluid can be expressed; a few days later there is often a slight milky

secretion, which finally disappears during the third week. This is popularly known

as 'witch's milk'. The explanation of this phenomenon is that the hormone which

stimulates the mother's breast reacts also upon the mammary tissue of the foetus.

Thus it is essentially physiological.

Mastitis of puberty is encountered rather frequently, usually in males. The

patient, aged about fourteen, complains of pain and swelling in the breast. In 80%

the condition is unilateral but the opposite breast may be affected later. The breast

is enlarged, tender and slightly indurated. Suppuration never occurs. The

tenderness subsides in fourteen days or so, but induration often persists for several

weeks. In some instances enlarged tender breasts may persist in males for a

prolonged period even up to years. In such circumstances it may be justifiable to

recommend local mastectomy, conserving the nipple.

Mastitis of mumps is usually unilateral, and more common in females.

Mastitis from milk engorgement is liable to occur about weaning time; and

sometimes in the early days of lactation when one of the lactiferous ducts becomes

blocked with epithelial debris. In the latter instance a sector only of the breast

becomes indurated and tender.

Bacterial mastitis, which is by far the most common variety of mastitis, nearly

always commences acutely. Although often referred to as mastitis of lactation, it is

incorrect to assume that acute mastitis in women is necessarily lactational. Of a

hundred consecutive cases of breast abscess, thirty-two occurred in women who

were not lactating; probably some were due to infection of a haematoma. In almost

every case the infecting organism is a staphylococcus. In cases where the infection

is acquired in hospital no less than 90% of the infecting staphylococci are

insensitive to penicillin.

Aetiology.—Mastitis of lactation is seen far less frequently than in former years.

Usually the intermediary is the infant; after the second day of life 50% of infants

harbour staphylococci in the nasopharynx.

'Cleansing the baby's mouth' with a swab is also an aetiological factor. The delicate

buccal mucosa is excoriated by the process; it becomes infected, and organisms in

the infant's saliva are inoculated on to the mother's nipple.

There seems little doubt that in the great majority of cases the precursor of

intramammary mastitis is failure of secretion to escape because one (rarely more)

of the lactiferous ducts becomes blocked with epithelial debris—a hypothesis that

is strengthened by the fact that, whether they are lactating or not, intramammary

mastitis and abscess of the breast are relatively frequent in women with a retracted

nipple. While stasis in some part of the lactiferous tree is a major factor in the

production of this condition, undoubtedly the older hypothesis—ascending

infection from a sore or an infected cracked nipple—must not be spurned. Once

within the ampulla of the duct, staphylococci cause clotting of milk. Within the

clot organisms multiply rapidly.

Clinical Features.—The affected breast, or more usually mainly one part of it,

presents the classical signs of acute inflammation, and what is aptly called 'the

cellulitic stage' of a breast abscess has been reached.

Treatment during the Cellulitic Stage.—The patient should rest in bed and,

pending the results of bacterial culture of her milk, be given an antibiotic

appropriate for a penicillin resistant staphylococcus, e.g. cloxacillin or

flucloxacillin. Support to the breast and local heat will help to relieve the pain and

permit examination of the inflamed breast daily, which is essential.

Unless there is some strong reason to continue breast feeding it is better to wean.

Suppression of lactation usually follows naturally upon the cessation of suckling

but if necessary bromocriptine can be given, 2-5 mg bd for 14 days. Stilboestrol is

no longer used for this purpose. If the mother insists on continuing breast feeding it

is safer to use the unifected breast only and to empty the infected breast of milk,

which may have a high bacierial content, by means of a breast pump. Boiling or

pasteurisation of expressed milk not only destroys its content of antibodies but also

greatly reduces its nutritional value to the infant.

Formation of an 'Antibioma'.—It is absolutely essential that an antibiotic should

not be given in the presence of undrained pus. In such circumstances, if an

antibiotic is given the pus in the abscess frequently becomes sterile and a large

brawny oedematous swelling remains in the breast and takes many weeks to

resolve. Sometimes there is excessive fibrosis and this, with the absence of

tenderness, had led to the mistaken diagnosis of carcinoma. It is better to explore

the mass with a wide-bore aspirating needle than to cause an 'antibioma' with its

attendant pain, chronicity, and ill health. Most 'antibiomas' are due to late,

inadequate, and ineffective antibiotics.

Indications for Operation.—The breast should be incised when, after emptying, an

area of tense induration is felt and/or when oedema of the overlying skin is found.

In contrast to the majority of localised infections, fluctuation is a late sign and

incision must not be delayed until it appears. Usually the area of induration is

sector-shaped, and in early cases about one-quarter of the breast is involved; in

many

later

cases

the

area

is

more

extensive.

Drainage of an Intramammary Abscess.—The usual incision is sited in a radial

direction over the affected segment. One parallel with the cutaneo-areolar margin

has a better cosmetic value and does permit access to the affected area. The

incision passes through the skin and the superficial fascia. A long haemostat is then

inserted into the abscess cavity. Every part of the abscess is palpated against the

point of the haemostat and its jaws are opened. All loculi that can be felt are

entered. Finally, the haemostat having been withdrawn, a finger is introduced and

any remaining septa are disrupted. Unless the abscess cavity is situated at the very

highest sector of the breast a counter-incision should be made at the most

dependent part of the breast and a drainage tube inserted. In this, almost more than

any part in the body, dependent drainage is essential.

Subareolar mastitis is not a true mastitis but results from an

infected (sebaceous) gland of Montgomery, or from a furuncle on or near

the areola. The inflammation develops insidiously, usually without

constitutional symptoms. When the patient presents early, there is often

an area of induration no larger than a pea. No matter how small, if a lump

can be felt, pus is present, and the abscess should be drained without

delay. Spontaneous rupture, if allowed to occur, does not cure the

condition; it merely results in recrudescence or chronicity.

Chronic intramammary abscess which follows inadequate drainage

or injudicious antibiotic treatment is often a very difficult condition to

diagnose: when encapsulated within a thick wall of fibrous tissue, the

condition cannot be distinguished from carcinoma without the

histological evidence from a biopsy.

Chronic Subareolar Abscess (leading to a Mammillary fistula).—A

recurrent subacute or a chronic abscess may occur apart from lactation in

women of the child-bearing age. The condition is a frequent complication

of long-standing retraction of the nipple the infection being restricted to a

single obstructed duct system. The abscess ruptures and subsides, only to

repeat the cycle over and over again at intervals of a few months when it

forms a chronic mammillary fistula. A non-infective inflammation such

as duct ectasia may also result in fistula formation.

Treatment.—Antibiotic therapy followed by incision and drainage is

useless. The fistula must be treated in the same way as a fistula-in-ano,

i.e. the track is laid open and saucerised

Retromammary Abscess.—Here the pus is situated in the cellular

tissues behind the breast, and in the great majority of cases the abscess

has no connection with the breast proper. Usually a retromammary

abscess originates from a tuberculous rib, infected haematoma, or

possibly from a chronic empyema, and treatment must be directed to the

relief of these conditions. A submammary incision allows the breast to be

retracted as necessary from the field of operation.

ERYSIPELAS

Of a character easily distinguishable from other forms of suppurative

inflammation, erysipelas represents the most completely non-suppurative

type of diffuse streptococcal infection. A lesion limited to the skin itself,

it illustrates, apparently, the reaction of a particular tissue to infection,

capable in other situations and in an altered state of virulence, of

producing a very different result. It arises from gross or microscopic

wounds, spreads rapidly, and almost invariably causes chills, high fever,

and such severe constitutional disturbance that delirium is quite common.

Sometimes there is a phlegmonous inflammation at its point of origin and

at other times none. Facial erysipelas spreads over the nose and cheeks in

the shape of a butterfly with outspread wings. In that case the infection

appears to enter from small ulcerations within the nose. This form of

disease may occur at any age, but the very young and old are particularly

subject to it. Rarely it passes over the entire body in a wave or succession

of waves; for though it is ordinarily self-limited, running a course of one

to three weeks, relapses and reinfections are far from uncommon.

Erysipelas appears as an intense blush upon the skin which becomes

glazed and moderately swollen. Its advancing edge is elevated and quite

sharply outlined. The exudate is in the form of an edema, well supplied

with phago-cytic leucocytes, but, since there is little or no solution of

tissue, non-suppurative. Indeed, solution and destruction of the skin is so

little marked that once the infection dies out, repair is rapid and complete.

Streptococci are present in the advancing margin of the lesion and may be

found in the blebs which sometimes appear upon its surface. They

disappear from its center as the disease spreads.

Treatment.—Owing to the rapid progress of erysipelas over considerable

areas, incision, which in any case would be likely to spread the infection

to deeper parts, is out of the question. Indeed, no local treatment has

much of any influence on the disease, though attempts have been made to

limit its spread by establishing a zone of artificial vascularity about the

lesion through painting the surrounding area with tincture of iodine or

crude carbolic acid (and alcohol). Hitherto the greatest progress has been

made by prophylaxis. The cleansing of accidental wounds in soiled skin,

the prompt treatment of seemingly trivial infections have greatly cut

down its incidence. The sulfonamides have revolutionized the treatment

of erysipelas, greati; lowering its mortality in both infants and adults. At

the moment, sulfadiazini is the drug of choice, and should be

administered in full therapeutic dose. Complete bed rest is obligatory;

fluids are forced orally—parenterally if necessary. Hot wet compresses

may be applied to the affected part. Fever usually lessens within 12 to 24

hours, and the lesion often disappear in 5 to 8 days.

Lymphadenitis.— Diffuse suppurative inflammation rapidly involves

those lymph glands placed in the course of the lymphatic vessels which

dram the diseased area. At first slightly swollen and tender, they may

later become ereatly enlarged and inflamed, even at a considerable

distance from the infection Thus a septic process, originating, perhaps, in

an abrasion of the surface of the great toe, may be followed, within a few

hours, or perhaps over night, by the appearance of a red streak which

wanders up the c-uf and thigh toward the groin. Even now, the superficial

group of lymph glands about the saphenous opening may be palpable as a

mass of tender elastic lumps the size of a pea or larger. If the original

focus upon the toe subsides the glands will usually subside as well. But it

is not uncommon to observe enormous enlargement and diffuse

suppuration in the glands of the groin some days or even weeks after the

healing of a local lesion which may,indeed, have appeared insignificant.

In the upper extremity, the cubital and epitrochlear glands may pick_up

infection from a lymphangitis which is spreading toward the axilla. Ihe

axillary group is very commonly involved but usually prevents the

process from advancing further. The cervical glands take up infection

spreading from the mouth, laws, face and scalp. The axillary, inguinal

and cervical groups •ire therefore of great importance as filters, catching

invading micro-organisms on their way to the general circulation,

reacting like other tissues to bacteria and their toxins, and thus affording

the body time and opportunity for defence against virulent and otherwise

overwhelming infection. Considering the fre-auency of their involvmcnt,

lymph nodes seldom undergo abscess formation. They soften reluctantly,

breaking down so gradually that suppuration is exceedingly slow and

incomplete. Treatment.—Should suppuration actually occur, judgment as

to when and how to operate is difficult. Ultimately, a mass of persistently

infected lymph nodes is likely to soften into a single or multilocular

abscess, but all the glands of the axillary or inguinal groups, as the case

may be, seldom undergo abscess formation at one time, or to the same

degree. Incision into such a mass will disclose, if made too early, a little

thin purulent fluid among a group of greatly enlarged glands, some of

which are reduced to necrotic fragments while others are firm or only

partly softened. Drainage is therefore ineffective and the attempt at

complete excision, though occasionally successful, is more apt to spread

the infection. Conservative measures, in the form of poultices or moist

compresses, bring comfort, and result finally in complete breakdown of

the glands or spontaneous healing. The sulfonamides are indicated in

overwhelming infections, but have little effect upon the lesion itself.

LYMPHANGITIS

This very common disease appears in two forms: (1), the reticular, a generalized involvement of the cutaneous mesh of lymph spaces marked by a

diffuse blush, and (2), the tubular, which is actually an infection of the

subcutaneous lymph channels. The visible sign of the second is a red

streak upon ?he kTwiich may advance with remarkable rapidity. If the

local infection from which it takes origin subsides, tho lymphangitis is

quickly resolved, the red streak disappears, and healing occurs leaving no

visible trace. On the other hand if the original focus spreads into the

subcutaneous tissues, the lymphangitis becomes swallowed up in the

more diffuse process which advances along and about it and which then

becomes a cellulitis. Lymphangitis almost necessarily loads to infection

of the lymph nodes in its course. It may convey infection into tendon

sheaths and joints, even into the general circulation. Such complications

occur in only a small percentage of all cases.

ANO-RECTAL ABSCESSES

In 60% of cases the pus from the abscess yields a pure culture of

Esch. coli; in 23% a pure culture of Staphylococcus aureus is obtained. In

diminishing frequency, pure cultures of Bacteroides, a streptococcus, or

B. proteus are found. In many cases the infection is mixed. In a high

percentage of cases—some estimate it as high as 90%—the abscess

commences as an infection of an anal gland. Other causes are penetration

of the rectal wall, e.g. by a fish bone, a blood-borne infection, or an

extension of a cutaneous boil.

A large percentage of anorectal abscesses coincide with a fistula-in-ano.

For this reason, anorectal abscess becomes a highly important subject.

Moreover, as antibiotics cannot reach the contents of an abscess in

adequate concentration, no reliance can be placed on antibiotic therapy

alone. A fistula is much more likely if bacterial culture of the pus

discloses bowel (as opposed to skin) organisms.

Classification of Ano-rectal Abscesses.—A clear understanding of

suppuration in this area is dependent on a concise knowledge of the

anatomy. There are four main varieties—perianal, ischiorectal,

submucous, and pelvirectal.

1. Perianal (60%).—This usually occurs as the result of suppuration in

an anal gland, which spreads superficially to lie in the region of the

subcutaneous portion of the external sphincter. It may also occur as a

result of a thrombosed external pile. If the haematoma is not evacuated, it

may become infected and a perianal abscess results. This is the most

common abscess of the region. Persons of all ages are affected, and the

condition is not uncommon, even in infancy and childhood. The

constitutional symptoms and the pain are less pronounced than in the

ischiorectal abscess because the pus can expand the walls of this part of

the intermuscular space comparatively easily. Early diagnosis is made by

inspecting the anal margin when an acutely tender rounded cystic lump

about the size of a cherry is seen and felt at the anal verge below the

dentate line. Treatment.—No time should be lost in evacuating the pus.

Operation.—Thorough drainage is achieved by making a cruciate

incision over the abscess and excising the skin edges—this completely

removes the 'roof of the abscess. Healing commonly occurs within a few

days.

2. Ischiorectal abscess (30%).—Commonly, this is due to an extension

laterally through the external sphincter of a low intermuscular anal

abscess (fig. IOI2B). Rarely, the infection is either lymphatic or bloodborne. The fat, which fills the ischiorectal fossa, is particularly vulnerable

because it is poorly vascularised; consequently it is not long before the

whole space becomes involved. The ischiorectal fossa communicates

with that of the opposite side via the post-sphincteric space, and if an

ischiorectal abscess is not evacuated early, involvement of the

contralateral fossa is not uncommon. Should an internal opening into the

anal canal ensue, a 'horseshoe' abscess develops enveloping the whole of

the posterior part of the circumference of the anal canal. An ischiorectal

abscess gives rise to a tender, brawny induration palpable on the

corresponding side of the anal canal and the floor of the fossa.

Constitutional symptoms are severe, the temperature often rising to 3839°C. Men are affected more often than women.

Treatment.—Operation should be undertaken early—as soon as it is

certain that an abscess is present in this area—remembering that

antibiotic therapy often masks the general signs.

Operation.—Stage I.—A cruciate incision is made into the abscess. A

portion of skin is sometimes excised but deroofing is not necessary in

every case.

3. Submucous abscess (5%) occurs above the dentate line (fig. i I37C).

When it occurs after the injection of haemorrhoids it always resolves.

Otherwise, it can be opened with sinus forceps when adequately

displayed by a proctoscope.

4. Pelvirectal abscess is situated between the upper surface of the levator

am and the pelvic peritoneum. It is nothing more or less than a pelvic

abscess and as such is usually secondary to appendicitis, salpingitis,

diverticulitis, or parametritis. Abdominal Crohn's disease is an important

cause of pelvic disease that can present as perianal sepsis. A relevant

point to remember is that rarely a supralevator abscess/fistula may be due

to over-enthusiastic attempts to drain an ischiorectal abscess or to display

a fistula, when a probe is forced through the levator ani/rectal wall from

below.

5 Fissure Abscess.—This is the name given to a subcutaneous abscess

lying in immediate association with an anal fissure. Drainage is achieved

at the same time as the fissure is treated by sphincterotomy.

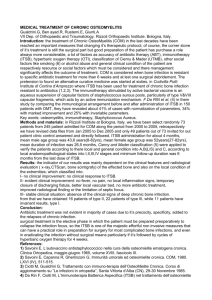

ACUTE OSTEOMYELITIS

Acute osteomyelitis used to be a common and serious, indeed often a

fatal, disease in children. Over recent years there has been a fall in the

incidence of the disease, probably due to an improvement in the general

health of children. At the same time antibiotics have made the disease

less serious: it need never now be fatal and should be curable.

Aetiology.—The bacteria reach the bone by the blood-stream. A primary

focus may be obvious in the form of a boil or an infected graze, but not

uncommonly no obvious source of infection is evident. Rarely the disease

may be secondary to a frank septicaemia or pyaemia. More commonly the

blood-borne infection takes the form of a bacteraemia.

It has been suggested that a lowered general resistance on the part of the

patient, and local trauma, may predispose to this disease, but the evidence

in support of these suggestions is unconvincing.

The usual causative organism is the staphylococcus aureus. Other

organisms which may be responsible include the streptococcus,

pneumococcus, haemophilus influenzae, staphylococcus albus and a

number of other organisms, no one of which is present commonly.

Pathology.—The disease always, or nearly always, begins in the

metaphysis. The infective process progresses through the thickness of the

cortex via the Haversian canals and as it does so causes thrombosis of the

vessels in the bone. As a consequence, by the time the infection reaches

the subperiosteal region of the bone a variable amount of the cortex may

have been infarcted. In the first 24 or 48 hours after the onset of the

infection, an inflammatory exudate forms deep to the periosteum,

elevating the membrane from the bone. Periosteal elevation is painful

and, since the periosteum is inelastic, the inflammatory exudate deep to it

is under tension. As a consequence the patient rapidly develops marked

toxic signs. Approximately 48 hours after the first symptom, frank pus

develops subperiosteally. Partly as a consequence of the resistance of

cartilage to invasion by the septic process, and partly because of the very

firm attachment of the periosteum (more accurately the perichondrium) to

the epiphyseal plate, transgression of the plate itself and consequent

interference with growth is rare. The inflammatory process progresses

along the length of the medulla causing venous and arterial thrombosis as

it does so. Subperiosteally, pus tracks both longitudinally and

circumferentially around the bone, stripping the periosteum and

interrupting the periosteal vessels. Thus progressively larger areas of the

cortex become infarcted and involved in the inflammatory process.

In the absence of treatment pus finally bursts through the periosteum and

tracks through the muscles to present subcutaneously. Eventually the skin

breaks down and pus discharges from a sinus which connects the bone

with the«skin surface.

The bone infarct in acute osteomyelitis is known as a Sequestrum.

Surrounding the sequestrum, the elevated periosteum lays down new

bone which entombs the dead bone within. This ensheathing mass of new

bone is known as the Involucrum. In the places where pus has broken

through the periosteum to form a defect in it, sinuses develop which are

represented in the involucrum by holes known as Cloaca (Latin) = A

drain. The development of such advanced pathology is now rarely seen

since modern treatment if adequate, aborts the disease before pus has

formed, and certainly before a significant amount of bone has died.

Two factors are responsible for the chronicity of this disease: the

presence of dead, infected bone which cannot be resorbed; and the fact

that the intraosseous abscess cavity cannot be obliterated because it has

rigid bony walls. As a consequence of these factors the body's normal

defence mechanisms (leucocytes and antibodies) together with any

antibiotics that may be given therapeutically are unable to reach all the

bacteria in the bone. Accordingly, although the disease process may be

sterilised in the living bone, recurrence is always likely.

Clinical Features.—Pain is the presenting symptom.

It is essential that an accurate history is taken so that the onset of the first

complaint of local pain can be timed exactly. The significance of this

feature of the history is discussed further under Treatment. The pain

gradually increases in severity, and the child becomes increasingly febrile

and toxic, at a rate dependent upon the toxicity and virulence of the

infective organism. It is usual for the mother to seek medical advice

within 48 hours of the onset of the first symptom.

Physical Signs.—The essential physical sign is localised tenderness.

When the doctor first examines the child, the child is likely to be irritable

and to resent examination. It is imperative that the physician should be

patient, and gently palpate the child's limbs until the exact area of

maximum tenderness has been identified. If this tenderness lies over the

metaphysis of a long bone, the diagnosis of acute osteomyelitis should be

presumed until it can be proved otherwise. The adjacent joint may contain

an effusion, raising the differential diagnosis of suppurative arthritis. The

joint itself however is not tender and although the child resists movement

of the limb, with patience it is possible to demonstrate that some

movement of the joint is allowed. This contrasts with acute suppurative

arthritis in which absolutely no movement is permitted. The temperature

is raised, often markedly so, and an associated increase in the pulse rate

occurs. Some days after the onset of the first symptom noticeable

swelling and heat may be detected in addition to tenderness. Finally the

area of the abscess (for such it is by this time) is fluctuant.

It is absolutely essential that blood cultures should be undertaken before

antibiotic treatment is commenced. In order to provide the maximum

possible chance of a positive culture, three separate venipunctures should

be made and from each venipuncture three aliquots' should be cultured

separately. The child's body surface should be searched minutely for

possible primary foci of infection and if these are found they should be

cultured.

Special Investigations.—Other investigations are of no diagnostic value

early in the disease. The E.S.R. and white cell count are usually raised but

this is entirely non-specific.

X-ray.—There are no abnormal radiological features in the first few days

of the infection. As time goes by, new bone can be seen deposited by the

elevated periosteum, but this sign does not appear until more than 10 days

after the onset of the disease and will then be demonstrable whether or

not the disease has been sterilised: it depends entirely upon the presence

or absence ofperiosteal elevation. Some rarefaction in the bone due to

local hyperaemia will also occur after 2 or 3 weeks but again does not

distinguish continuing osteomyelitis from the sterilised disease. The

radiological appearances of chronic osteomyelitis are dealt with

elsewhere.

Treatment.—The child is admitted to hospital and the limb is splinted,

but in such a way that easy access to the tender area is retained. The

outline of the tender area is marked on the skin.

If the patient is first seen within 48 hours of the appearance of the first

symptoms, antibiotic treatment is begun immediately after appropriate

samples have been taken for blood culture. Acute osteomyelitis is one of

the few diseases in which it is justifiable to begin antibiotic treatment

without waiting for bacterial sensitivity, a peculiarity which stems from

the fact that if the disease can be sterilised within the first 48 hours,

complete resolution can be guaranteed. If sterilisation fails or is not

attempted in this time, the disease may become chronic, so generating

life-long disability and a possible cause of death. The great majority

(about 80%) of the isolates from osteomyelitis are Staphylococcus aureus

and cloxacillin should be administered at a dosage of 100-200 mg/kg

body weight in divided doses intravenously until the child is clinically

well, has no fever and the local signs have decreased. Oral therapy, with

flucloxacillin can then be given. In addition, benzyl penicillin should be

given intravenously (0.25-1.0 million units every six hours). For

penicillin-hypersensitive patients a cephalosporin may be given

intravenously. In children under three Haemophilus influemae may be a

responsible organism and especially affects the small bones of the hands

and feet. At the present time ampicillin 250 mg q.d.s. intravenously is

recommended. Unfortunately antibiotic resistance amongst organisms

causing osteomyelitis creates problems. The staphylococci are usually

resistant to benzyl penicillin and ampicillin and therefore require a

penicillinase-stable penicillin. Most strains of Haemophilus influemae are

currently susceptible to ampicillin but if failure to respond is thought to

be due to a resistant organism, chloramphenicol should be substituted.

Other antibiotics may be substituted if they are dictated by the sensitivity

tests.

If the patient is first seen 48 hours or more after the onset of the first

symptom, the possibility arises that pus is present. If pus is present, it may

be sterilised by antibiotics, but the general surgical principle applies to

bone as to other tissues that an abscess requires surgical evacuation. The

presence of pus may be difficult or impossible to detect with certainty

since fluctuation is late to develop. Fluctuation cannot be demonstrated in

the early stages of abscess formation because the periosteal membrane is

tense, the involved bone is often deep to muscle, and the area is too

tender to palpate firmly. Therefore the surgeon has to rely upon his

general impression as to the severity of the disease and his knowledge of

its duration in deciding either to treat the patient initially with antibiotics,

or to combine this therapy with incision of the tender area.

If it is decided to rely on antibiotic therapy alone in the belief that no pus

is present, antibiotics should be given and the effect of this treatment

upon the toxic signs and upon local tenderness should be watched very

closely. If the antibiotic is controlling the disease, and if no pus is present,

the temperature will subside to become normal within 2 or 3 days and

tenderness will progressively disappear. If, on the other hand, the

antibiotics are inappropriate to the sensitivities of the organism or pus is

present, the temperature is likely to settle but not to normality: spikes up

to 38°C will continue. If this occurs, the tender area must be explored

surgically with a view to evacuating pus if any is present and to obtaining