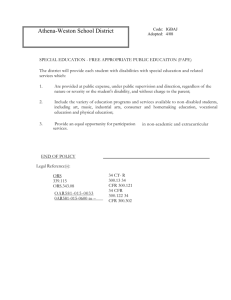

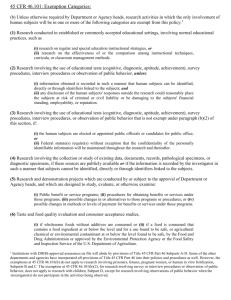

Institutional Compliance with Federal Non

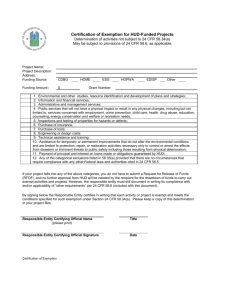

advertisement