morenian tools save time and deepen environmental

advertisement

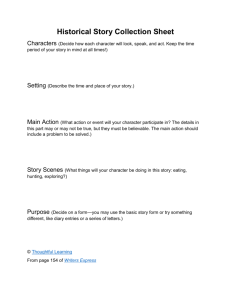

1 Marjut Partanen-Hertell M.Sc. (Tech), Senior Coordinator at the Finnish Environment Institute SYKE Psychodrama Trainer (TEP) at the Finnish Moreno Institute SMI Chairperson of the Association of Finnish Trainers in Moreno Psychodrama MOPSI arua@welho.com , marjut.partanen-hertell@ymparisto.fi MORENIAN TOOLS SAVE TIME AND DEEPEN ENVIRONMENTAL COLLABORATION PROCESSES Keywords: Moreno, relationmetry, sociodrama, mental model, systems intelligence Abstract: Environmental issues bring together people from various backgrounds for collaboration. They may have the same explicit aims but their immaterial cultural conserves e.g. mental models, rules and values their tacit knowledge - often diverge. Morenian tools such as sociodrama as part of the work process may concretize systems and mental models, associated attitudes and values, thus helping create a collective perception and free time for real problem-solving. 1. Introduction To take part in an international environmental planning and decision-making processes is demanding. The participants are in the middle of interactive and interpersonal communication, where pure expertise is not enough. Skills to express your self and listen to others are crucial when using multiple professional and national languages. The process is also intrapersonal, because to gain successful results the participant has to be ready for change and modify his earlier opinions and attitudes, even accept new facts according to the information that is flooding over him. Processes in these kinds of circumstances take a lot of time and energy, and it is not always easy to keep the working atmosphere open and positive. My paper will focus on ways to enrich and speed up multinational collaboration connected to environmental, social and economical themes. Great interest lies in the possibility to unite explicit planning methods including computerized models with Morenian tools, which reach the subconscious wisdom and increase internalized knowing thus enhancing systems intelligence and common mental models for creating collective perceptions of environmental issues distributing tacit knowledge building a foundation for sustainable collaboration required for reaching successful outcomes for transnational and trans-cultural time consuming processes resolving conflicts during the preparation and implementation of the decisions 2 saving time by helping participants move from disorientation and confusion to realization and innovation. Systems intelligence involves the ability to use the human sensibilities of systems and reasoning about systems in order to adaptively carry out productive actions within and with respect to systems (Saarinen & Hämäläinen 2010). It is thus scaling up a person's problem solving capabilities and invoking performance and productivity in everyday situations. (Hämäläinen & others 2004). It could be simply said that systems intelligence connects systemic awareness and sensitivity to the concept of emotional intelligence that Salovey and Mayer presented in 1990. It is obvious systems intelligence is needed, when environmental issues nowadays bind together various interest groups in a very complicated way. A mental model is a representation of a material or immaterial real-world system in the mind of a person. Our mental models define the way we see the world around us and how we act in it (Senge 1990). Mental models help a person shape her behaviour in a sensible way and may save time and energy in decisionmaking. In this way they come close to Moreno's concept of cultural conserves in their immaterial form (Moreno 1946, Partanen-Hertell 2005). New knowledge of environmental problems demands us to recreate and expand our mental models defining these problems. Tacit knowledge is known by an individual, but difficult to communicate to the others, thus “we can know more than we can tell“(Polanyi 1983). This kind of knowledge often consists of culture and habits or is bound to using equipment. It produces almost automatic thinking and behaviour. People may not be aware of their knowledge or its usefulness to others. The transfer of tacit knowledge usually requires besides training or personal experience the personal contact, trust and a special place (Nonaka & others 2000, Nonaka & Takeuchi 1995). Tacit knowledge can both expand and restrict our possibilities to solve problems – the ability to examine it interactively is essential. Morenian methods include for example sociometry, sociodrama, role-playing and role-training. Sociometry (Moreno 1953) has inspired the use and development of tools that I call relationmetry. Relationmetry explores interactive systems such as connections, interdependencies, feedback, attitudes, roles and other interaction dynamics between issues. Relationmetry helps concretize and externalize mental models or insights that people consciously or un-consciously have in their minds concerning various material or immaterial issues (Partanen-Hertell 2005, 2002) such as “environmental awareness”, “mining industry and the environment” or “Sao Paulo”. In warming up, supervision and consultation psychodramatists use means such as symbol work, collages, card techniques, and the diamond of polarities and time lines that can also be used as relationmetric tools. Organization and process consultants use a lot of tools for participatory processes that I connect to relationmetry as well. These tools may be purely qualitative or semi-quantitative also assigning numerical values to variables. 2. Themes, participants and processes of environmental collaboration Environmental issues and problems are often urgent. They tangle multi-scale scientific, economic and social viewpoints together, not to mention national and cultural attitudes and interests (Figure 1). Good sustainable decisions are based on common understanding and goals which may not be identical but which are at least pulling towards the same direction. The themes and topics of a collaboration where Morenian methods could be used vary from the analysis of earlier environmental accidents to the exploration of communicative ways to influence water protection (Partanen-Hertell 2010), and from developing a good basis for a present concrete project (Partanen-Hertell 2009 c) to creating scenarios for future pan-European water resources. These tools may also help in comprehending and visualizing the system of activities in an organization (Partanen-Hertell 2009 d). The collaboration process concerning a particular theme may need just one workshop (Figure 2, a), or it might last for several years (Figure 2, d). Therefore, it is important to select, motivate and invite the relevant 3 interest groups to collaboration according to the purpose and objectives of the process. The use of the tools of relationmetry and sociodrama may help identification of interest groups or analysis of future challenges. 4 Planners: Governmental Municipal Private… Lobbyist: Industry NGOs Transport… Local stakeholders: Land owners Businesses Residents… Creating together collaboration knowledge & solutions Experts: Universities Local experts Research institutes… Decision makers: Authorities CEOs Politicians The judiciary... Figure 1. Parties and goals of transnational environmental planning; a system of interest groups and their cultures, countries, languages, hierarchies, motives and knowledge. The Finnish Environmental Institute co-coordinates a four year project SCENES (2006-2010) funded by the European Union, that covers the European Union member states and the neighbouring countries. It aims to address the complex questions about the future of Europe's water resources. In the first phase largely extant scenarios were selected and readily available information on drivers and policies assembled and run through an existing quantitative computer model of pan-European water availability (WaterGap). In the second phase using an iterative approach more refined scenarios (storylines) up to 2025 and 2050 were developed at both the pan-European and regional scales, with highly participatory scenario panels. The third phase involves a synthesis of the information and dissemination of the project outputs to external stakeholders and end-users. An evaluation of the participatory scenario processes gives new information on the functioning of the science-policy interface, and on challenges the European water management may confront in the future. (Kämäri & others 2008) The SCENES considers inter alia existing scenario development methods and innovates to improve them in a 'learning-by doing' participatory process. The starting point was the Storyline-And-Simulation (SAS) method which involved the development of narrative storylines during a series of stakeholder scenario workshops. These qualitative scenarios were subsequently translated to a set of quantified parameters, which were the input for a quantitative model (WaterGap). Participatory scenario workshops used qualitative and semiquantitative methods to create the qualitative scenarios (storylines), which promote a way to communicate complex information and can incorporate a wide range of views about the future. The storylines explore, for example, how social, financial, economic and cultural changes will modify the future demand for water in Europe and how the coping capacity of people in various parts of Europe to drought can be increased over time. The quantitative scenarios were used to check the consistency of the qualitative scenarios, to provide needed numerical information and to 'enrich' the qualitative scenarios by showing trends and dynamics not 5 anticipated by the storylines. Qualitative and quantitative scenarios provide a powerful combination and compensate for each others deficits. (Kämäri & others 2008) The SCENES serves well as an example of a complex long-term collaboration process in an environmental context, which explores the views, values and mental models of stakeholders from pan-European, regional and pilot area levels, and strives to connect them to each other and to quantified data (Figure 2, e). Special attention was paid to the description of the methodology used for scenario development (Vliet & others 2007) and to the design of the participatory scenario-building process (Kaljonen and Varjopuro 2007). In order to make the facilitators of the participatory scenario workshops familiar with the selected methods the SCENES arranged a scenario development training seminar for them. In the SCENES eleven separate sets of panels were formed, all of which produced their own set of scenarios. The panels met three to four times at half a year intervals. At each level panels were formed consisting of a meaningful mix of stakeholders (Kaljonen and Varjopuro 2010). In 2010 before the end of the SCENES, there will be an evaluation of the used participatory methods which included Talking Pictures, card techniques, spider-grams, Collages of Future, Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping (FCM) and timelines from storyline development and scenarios to back-casting. Experiences so far show that the people who have participated in SCENES panel workshops value the process and the networks build highly. Building up visions of divergent futures in a qualitative manner encourages a deliberative and experimental spirit; whereas building one single FCM of the system spurs participants towards a consensual view. Using individual post-its and spider-grams sees the variety in views as a necessity; whereas the social dynamics of group work seeks compromises. The usage and sequencing of the methods will have a qualitative impact on the outcome. Also time devoted to exercises and group work plays a decisive role as does the ways the work has been facilitated. It seems that developing the participatory scenario-making as a method for forming tangible and robust social choices requires special care and devotion. Commitment does not appear automatically; quite the opposite and it is dependent on the mobilisation of linkages that the process of knowledge production has or is able to build to actual decision making. (Kaljonen and Varjopuro 2010) In an overview of available participatory methods collected by the SCENES there are several methods that I would connect to relationmetry but only one (role-playing) that is a pure psychodrama technique. Roleplaying, however, was not used in the project. Successful and safe applications of sociodrama, as well as many of the tools of relationmetry require the director to have throughout training in Morenian methods. On the other hand a wider use of Morenian methods could save time, enrich the process and deepen the results by giving the participants more insight emerging from unconscious and co-unconscious levels. However, Moreno (1977 p. vii) considered that co-conscious and co-unconscious states are by definition, such states which the partners have experienced and produced jointly and which can, therefore be only jointly reproduced or re-enacted. Therefore, the challenge is how to tie the outcome to the reality outside the group. 3. Connecting the Morenian tools to environmental collaboration The Morenian methods may be used in environmental collaboration in the form of a workshop or a cluster of interlinked workshops (Figure 2, a, b and c), as a part of a single process (Figure 2, d) or in connection to a complex process such as SCENES (Figure 2, e). The goal is to get a picture of various interpretations of 'facts' and causalities or of human behaviour connected to them – usually in qualified or semi-quantified terms. Frequently, there are hidden agendas and different understanding of the key points, which include a human set of attitudes and emotions. The aim may also be a learning process for participants or an attempt to produce semi quantified or quantified factors for further analysis, like the participatory methods were used in SCENES. 6 a. b. c. d. e. Figure 2. Various structures of participatory processes. The blue ellipses symbolise Morenian or other participatory workshops, the boxes the use of explicit planning methods and the stars the use of computerized models. In participatory workshops the process may be a mixture of collaborative dialogue and Morenian exercises (Partanen-Hertell 2009 a). Below I describe the main steps of the work in a manner that is familiar to psychodramatists (Partanen-Hertell 2010, 2009 b): Background preparation, connecting the Morenian tools to the collaboration process and warming up the facilitator or director of the workshop: The focus is on gathering information on the task and theme of the collaboration as a whole, identifying and analysing the stakeholders and a possible combination of them to build up a participatory group, and analysing the conceivable goal and available Morenian methods. Also an analysis of the directors own set of values and goals is needed (Wiener 1997). The main concern is which specific issues in these contexts could be explored and worked out with of Morenian approaches. Creating trust and tele among the participants: Most important in the beginning is forming a group from the participants, getting to know its members and creating enough trust for the next step. This awakens questions that have to be answered such as: What kind of group is this? What are the goals of the gathering? Which stakeholders are present? How are the participants connected to the collaboration and to each other? Who has power? How is the theme linked to me and to my individual concerns? What worries do the other participants have about the theme? Tools: Discussion, storytelling, symbols etc. 7 Warming up the group: It is important to warm the group up to the actual task or theme and to the issues around it, and to avoid working at too intimate a level. Questions linked to this step are: Which issues are connected to the theme? How are the questions or the participants connected to each other? What kind of mental models or cultural conserves around the theme exist in the group? What kind of resistance and defences are present? Tools: Discussion, short narrative examples, relationmetry such as Talking Pictures and card techniques. The case? Figure 3. Individual mental models and values connected to the case; relationmetry and symbol-work unveil individual tacit knowledge. The case Figure 4. A common mental model and values connected to the case; relationmetry and symbol-work combine individual knowledge unveil new issues and create new values. Setting up the stage and deciding upon a scene: 8 In this kind of work the stage is set up by creating common mental models of the theme. This is done by unifying the mental models of the participants (Figure 3 and 4). The concrete common mental model or stage can be set up on a blackboard, table or on the floor. The 'issues' may be factories, lakes, organizations, forests, shops etc. and the links between them. The goal is not consensus but visualising different views and studying how they are connected. When the 'big picture' is ready it is possible with the help of it to focus on a real or imaginary case. Related questions are: What kind of material or immaterial issues is bound to the topics in the real world? What kind of relations and effects do they have on each other? What kind of dynamics connects the issues together? What kind of attitudes and emotions are bound to them? Is something missing? What is really important here? Where could we focus? What kind of scene, time, roles and script could illustrate this 'world'? Tools: Relationmetry with symbol work, scoring Taking roles and acting: The next step is to wake the scene to life and to deepen the level worked at by personal actions. The methods of sociodrama are used at this step and it is possible that the whole group is creating a real scene and building up a sociodramatic stage. Using this creative group process the participants explore goals, values, attitudes and problems that tend to arise in teams, networks or collective relationships by taking assigned roles in dramatic acts. The participants are asked to take some role from the stage – maybe a role that they have earlier been talking about. This role is usually human, preferably not their own, but can also be an institution or animal or any other object found on the stage. The role of the facilitator changes into the role of a sociodrama director. It is important to know with diverse sociodramatic techniques help the participants get insight in what kinds of goals, connections, attitudes, emotions, and hidden agendas are bound to various roles. (Figure 5). Tools: Sociodrama vignette or the first act of a long sociodrama with role-taking, role reverses etc. Changing and developing the roles and scenes: It may be possible to further explore the stage together from various standpoints linked to the theme by helping the roles to develop and the scenes to change. There may be different gatherings of people or the timeline may be shifted backwards or forwards. The focus is on questions: What are the main concerns from different positions? What are the trends for the future? What in the past has led to the current situation? What is unfolding from the unconscious and co-unconscious of the participants, when examining the case / the created common example? Tools: Sociodrama with multiple acts and scenes, and various sociodrama techniques. Catharses of intellect, attitudes and emotions: There usually occur experiences among the participants that could be named catharses of intellect, attitudes or emotions. This often happens when the participants are gathering the experiences and views from the roles, actions and storylines of the sociodrama and integrating them. The director may help the process along with questions such as: When really looking inside the roles you have taken; what do you find? Tools: Monologues, letters, writing on colourful tags, symbol work, relational and social atoms, sociometry. 9 Figure 5. Sociodrama and role-play; the participants may explore goals, values, attitudes, connections and problems by taking assigned roles. Sharing: As always when working with powerful Morenian methods sharing is essential. On a personal level it means expressing emotions, experiences and views connected to the roles, storyline and to real life: What touched and impressed me here? What have I experienced here which reminds me of my real life? Tools: Discussion in pairs or small groups, connected also to the group as a whole. Processing: Some time after the sharing the processing of the sociodrama and relationmetry is done to deepen the understanding of the theme and the issues connected to it. Natural questions in this step are these: What did we understand and learn about the case? How is the systems intelligence of a person activated when stepping in multiple other shoes? What is important to bear in mind or do when proceeding? What kinds of commitments are needed among the stakeholders? Tools: Discussions in small groups and with the whole group, relationmetry, spider-grams, matrix. Documenting: In order to connect the outcomes of Morenian work to the overall process, good documentation and rendering the outcome to fit the formal communication and decision making of the overall process is essential. The group and the director ought to decide how it is best to communicate the result to others and how is it possible to consolidate the commitments needed. Tools: Collecting material produced, observers taking notes and transcribing discussions, video, tape recorders, photos. Follow up: There is a need for follow up and evaluation especially when the work with Morenian tools is a part of a complicated collaboration. The follow up process in long term collaboration also gives the opportunity to make adjustments to the Morenian working process. The focus here is on questions such as: What kind of impacts the work had on the whole collaboration? Were the outcomes useful in the long haul? What could be modified to get better results? How to disseminate experiences to a wider audience? 10 4. Relationmetry Relationmetry is a context in which to examine dynamic systems that may be interlinked with other systems and factors or 'drivers'. The characteristics and dynamics of the systems may be explored qualitatively and semi-quantitatively and in many different depths using facts, tacit knowledge, intuition and emotions. The tool-box of relationmetry includes card techniques, symbol work, role-taking, scores and weights etc. used in many different ways. The outcomes may be analysed and described with tools such as: Relation matrix Relation atoms Relation-grams Relation maps Miniature of a "world". Work with relationmetry may strive at a common mental model for a group which gathers together diverse viewpoints. It may not be aiming at a consensus but at a common understanding of similarities and differences in views, values and goals of the participants. At the same time relationmetry helps create a common language among the participants. It may also serve as a basis for a sociodrama or role training and especially for future collaboration. With relationmetry it also is rather easy to find out the 'hot pots' where new or ongoing crisis are steaming or the 'cool spots' where all development has stagnated. These are often the focus areas of further work. The level of relationmetry may vary from intellectual clarification to a deep intimate and personal exploration. The tools used impact this level. Discussion may keep the work on surface level. Writing on a blackboard makes the dialogue more 'serious'. Tags and post-it cards on the wall are less emotionally activating than the same tools in colours on the table or on the floor. Simple symbols like buttons often activate the unconscious less than complicated symbols such as picture magnets, Lego bricks, puppets, scarves, stones and flowers. Taking a role in a relation atom already demands trust and personal courage and developing this role or creating a new one demands even more so. At the same time it makes it possible to reach some essential elements of the theme which dwell in the depths of the unconscious. 5. Discussion This paper leaves many points of interest and questions open especially in connection to the following three areas: the collaboration process, Morenian tools and relationmetry. Below I present some viewpoints of them: Aiming at consensus may kill the various views of the participants and at the same time the richness of reality. The participants should see themselves as individuals and not as representatives of an interest group. On the other hand it usually improves the outcome if all the stakeholders are represented in the group in order to get all the relevant views into the process. How does the selecting and forming of the group impact the participants' willingness to bring forth their own opinions? The need for time in the various stages of the process is significantly different when using Morenian methods compared to traditional workshops and seminars. A lot more time needs to be reserved on the warm up and group formation and on building trust. The real pay back of the using these methods usually come from their efficiency and from the depth of the results. The skilfulness of the facilitator to make use of the natural stages of the group, such as 'forming, storming, norming and performing', contributes to the whole collaboration process. An interesting future point of research is the impact that the open communication of each participants mental models concerning the topic at hand has on lessening future problems stemming from hidden agendas etc. Can it be proved that a lot of time and throw backs can be saved in the continued work after the Morenian part especially in the 11 implementation process due to the hidden agendas and different mental models having been unveiled already during the earlier stages? Relationmetry seems to be able to unveil individual tacit knowledge and mental models and combine them to a common model that often also contains conflicts. This outcome represents more or less the reality of the participants. Is it possible to analyse and utilize the potential increase in systems intelligence while using Morenian tools during the collaboration process? Could a method be found for researching how much the Morenian methods can increase the transfer of tacit knowledge between the participants and further from the participants to their peer groups, during and after the collaboration process? It is important to document well common understandings and consolidate the commitments reached. Also the significance, relevance and character of the outcome should be realized. It can be misleading, when some semi-quantitative results of Morenian workshops are used as input data 'facts' for computerized models which might not be able to understand the 'here and now' momentary character of Morenian work. Connected to this also some other questions rise such as: - Which specific issues could be worked out by way of Morenian approaches and what could be the benefits or the pitfalls? - How should we handle the invisible power and the level of intimacy in the process? - How to read experts´ vocabularies, cultures, languages and values accurately enough? References Hämäläinen, Raimo P. and Esa Saarinen (eds.). 2004. Systems Intelligence – Discovering a Hidden Competence in Human Action and Organizational Life, Helsinki University of Technology: Systems Analysis Laboratory, Research Reports, A88. (Freely downloadable at www.systemsintelligence.tkk.fi) Kaljonen, M., Varjopuro, R., 2010. Experiences gained from the participatory scenario-making workshops. Water Scenarios for Europe and Neighbouring States, SCENES Newsletter 5, January 2010. (Freely downloadable at http://www.environment.fi/syke/scenes) Kaljonen, M., Varjopuro, R., 2007. Design of participatory scenario-building process and their linking to dissemination activities, SCENES Deliverable 5.2., Finnish Environment Institute, Helsinki, Finland Kämäri, J., Alcamo, J., Bärlund, I., Duel, H., Farquharson, F., Flörke, M., Fry, M., Houghton-Carr, H., Kabat, P., Kaljonen, M., Kok, K., Meijer, K.S., Rekolainen, S., Sendzimir, J., Varjopuro, R., Villars, N. 2008. Envisioning the future of water in Europe – The SCENES project. E-Water 2008, Official Publication of the European Water Association (EWA). The article and further information of the SCENES project is available through the project web-site at: http://www.environment.fi/syke/scenes Moreno, J. L. 1977. Psychodrama. Vol. I, New York: Beacon House Moreno, J. L. 1946. Psychodrama. Vol. I, New York: Beacon House Moreno, J. L. 1953. Who Shall Survive? Foundations of Sociometry, Group Psychotherapy and Sociodrama. Beacon, NY: Beacon House Inc. Nonaka, I., Toyama, R. & Konno, N. 2000. SECI, Ba, and Leadership: a Unified Model of Dynamic Knowledge Creation. Long Range Planning, Vol. 33. Nonaka, I. & Takeuchi, H. 1995. The knowledge creating company. N.Y.: Oxford University Press. Partanen-Hertell, Marjut. (In press, probably 2010). Sociodrama in Finland - an environmental context. In Sociodrama in a changing world: An anthology of international developments. R. Wiener, D. Adderly and K. Kirk eds.). Www.lulu.com 12 Partanen-Hertell M. 2009 d. Kansainvälinen toiminta vesivaratehtävissä (English Summary: International activities in water resources management). Reports of the Finnish Environment Institute 32/2009. Helsinki: FEI (SYKE) http://www.ymparisto.fi/default.asp?contentid=352629&lan=fi Partanen-Hertell, M. 2009 c. The application of the tools of sociometry, sociodrama and other action methods in the planning process for dealing with environmental issues. Unpublished paper. Abstract in 17th Congress of IAGP. Rome 24.-29.8.2009. Partanen-Hertell, M. 2009 b. In search of different perceptions, hidden agendas, veiled attitude and a common language in the setting up of a trans-boundary planning process. Abstract in 17th Congress of IAGP. Rome 24.-29.8.2009. Partanen-Hertell Marjut. 2009 a. A Cross-cultural Encounter with Environmental Problems, in the compendium of articles from the Second International Sociodrama conference, March 6 – 7, 2009, Helsinki, Finland Partanen-Hertell, M. 2005. Systeemiälyn ja mentaalimallien kehittäminen morenolaisilla keinoilla (Developing systems intelligence and mental models by Morenian means). In: Miten käytän toiminnallisia menetelmiä? Psykodraaman ohjaajat kertovat, Tarja Janhunen & Sirkka Sura (eds.) : pp. 137-150. Resurssi, Tampere, Finland Partanen-Hertell, M. 2002. Luova työyhteisö. Morenolainen lähestymistapa organisaation kehittämiseen. (A creative working community, the Morenian approach to organizational development). Arua, Helsinki. Polanyi, Michael.1983. The Tacit Dimension. First published Doubleday & Co, 1966. Reprinted Peter Smith, Gloucester, Mass. Saarinen, Esa and Raimo Hämäläinen. 2010. The Originality of Systems Intelligence. In Essays on Systems Intelligence. Hämäläinen, R. and Saarinen, E. (eds.). Systems Analysis Laboratory. Aalto University, School of Science and Technology. Espoo, Finland. (Freely downloadable at http://www.systemsintelligence.tkk.fi ) Salovey, Peter and John D. Mayer. 1990. Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, vol. 9, pp. 185-211. Senge, P. M. 1990. The Fifth Discipline; The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. Doubleday Currency, New York. Vliet, M., Kok, K., Lasut, A., Sendzimir, J., 2007, Report describing methodology for scenario development at pan-European and pilot Area scales, SCENES Deliverable 2.1, Wageningen University, Wageningen, Netherlands Wiener, R. 1997. Creative Training: Sociodrama and Team-building. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.