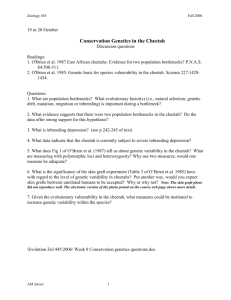

na cheetah conserv strategy 2

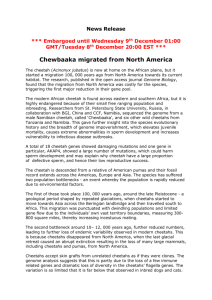

advertisement