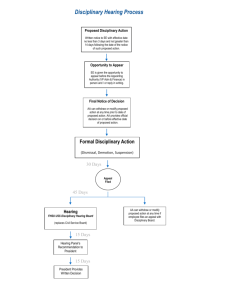

Conducting a disciplinary investigation and hearing

advertisement