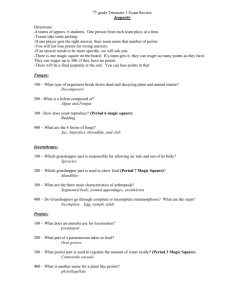

Magic and C17 Science: Retention and Rejection

advertisement

Magic and C17 Science: Retention and Rejection The Hermetic tradition raised the question of whether there was a wider range of influences involved in magic. Paracelsus, who was influential throughout the C16 and C17, adopted a magical view of the world, seeing it as non-mechanical and alchemical and worked within the empirical tradition in order to make use of occult properties. Francis Bacon, although hostile to some magic because he regarded it as an illegitimate short cut to knowledge, nevertheless acknowledged that this knowledge needed to be made public. His views on magic therefore had a moral dimension in that his attacks on magic were the result of his objections to the improper gaining of knowledge not the knowledge itself. In some ways this was the result of the association of magic and religious enthusiasm, despite the fact that magic was associated with sedition and that the power of prediction was seen as socially subversive. In this sense Descartes world picture, as a mechanical model, can be seen as nonmagical (and a significant step in the decline of magic). Thomas Sprat (of the Royal Society) was against magic and made attacks on the use of astrology and alchemy. It was his belief that the new science was intended to free people from these ideas. Yet many members of the early Royal Society continued to be involved in magic. Ashmole was a devotee of alchemy and astrology and gave Charles II advice, as a result of star-gazing, on how to manage his political opposition. John Aubry, in his “Brief Lives” attempted to test astrology and refine it as a result of these tests. In some senses this is a classic magical text in that it also contains magical spells. Many of the great men of the time had similar magical beliefs Robert Boyle was fascinated by accounts of witchcraft and funded translations of French accounts of witchcraft. He was motivated by collecting details of witchcraft in order to provide empirical evidence of Gods existence. He regarded alchemy as true, and a possible means to manipulate the universe. He was interested in testing alchemy and the changing of base metals into gold and corresponded with alchemists using encoded messages which was part of the alchemical tradition, all of which was at odds with the mechanistic rationale Henry Moore was a Cartesian enthusiast who later saw it as materialist and likely to banish God. He was constantly looking for a “spirit” of nature, a continuously working spiritual force Newton is seen as the paradigm for the scientific revolution. Yet vast quantities of his manuscripts deal with alchemy. David Brewster, Newtons C19 biographer did not overlook this aspect but made little of it. J.M. Keynes claimed that “Newton was the last of the magicians” who saw the universe as a riddle to be searched for clues as to its causes. Recent scholarship sees Newton as looking for information useful within mechanical and philosophical contexts. But the notes in his manuscripts clearly show attempts at alchemical usefulness in its fullest sense. R.S. Westfall’s study of Newton’s alchemy and relationship with philosophy place them firmly within the alchemical tradition, evidenced by both the method and anticipated outcome of his experiments and the language he uses to explain and describe them. This interest took place in the same period as his Principia and suggest a close relationship between his alchemy and (natural) philosophy. His dissatisfaction with the world-view of Descartes – which he saw as inadequate and materialistic- he looks for alternative ways of looking at the world. Alchemy is useful in promoting the idea of active principles in the universe and can be argued was suggestive of the idea of gravity (corresponding to the idea of spiritual forces pulsating through the universe) because of the similarity of ideas. But how typical was Newton of other scientists/natural philosophers of the time. The fact is he was not at all typical. He was someone who did everything in extreme and unusual ways for example his religious manuscripts where he depicts Christ as a mortal man. Boyle on the other hand was concerned with doctrinal correctness and the problem of moral legitimacy. His interest in magic was a consequence of his belief that attempts to gain true but illegitimate knowledge endangered the mortal soul as and as a result he stuck to an experimental level. Newton had no such qualms. Boyle’s distrust of magic was on moral grounds. He saw the reformation and the progress it suggested as anti-magical (see Keith Thomas). John Flamsteed was fascinated by astrology but gradually came to reject it because of what he saw as the inherent antagonism with religion and the idea of discovering “unsuitable” knowledge. His primary reason for rejecting astrology was rationalistic in that he saw no reason in nature for the validity of astrology. The mechanical universe does not provide explanations ad that the principles o astrology were capricious and not fit scientific criteria. He attempted to generate empirical evidence by comparing the lives of individuals with their astrological predictions. Robert Hooke was outright anti-magical as demonstrated by his attack on Henry Moore and his “spirit of nature”. All of Hooke’s explanations were based on mechanical principles. Yet even he conflated the idea of active spirit with conjuring and the notion of what spells are necessary to make natural things happen in the way that they do. His rejection of magic was on Cartesian grounds and epitomises the expected attitude to magic of the time. The magical interests of members of the Royal Society were carried out in private and rarely discussed publicly where a sceptical attitude prevailed that excluded magic to a degree not matched privately. This polarisation of science and magic, both private and public, increased throughout the period and the attitude shown by Hooke became increasingly prevalent, to the extent that early biographies were rewritten to exclude any mention of magical interest. One reason for this was increasing pressure from various quarters but particularly the worry about being branded an atheist and/or having an exaggerated interest in materialism. But the continued pursuit of magic by people like Boyle and Newton was because they believed in it and thought there were truths to be discovered and leads to the question of whether Newton’s major discoveries were the direct result of his magical interests?