PERSISTENCE DURATION OF IMMUNOGLOBULIN G ANTIBODIES

advertisement

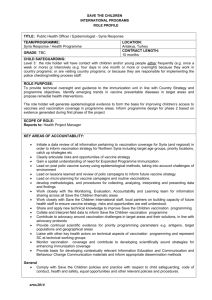

PERSISTENCE DURATION OF IMMUNOGLOBULIN G ANTIBODIES TO RIFT VALLEY FEVER VIRUS IN SHEEP AND GOATS SERA AFTER VACCINATION By Abdelhamid A. M. Elfadil and Emad S. Shaheen Campaign for Control of Rift Valley Fever, Ministry of Agriculture, Jazan, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. E-mail: aamelfadil@yahoo.com KEYWORDS: Rift Valley fever, Vaccination, Immunoglobulin G, Herd immunity, Control strategies. ABSTRACT Duration of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies to Rift Valley fever (RVF) virus after vaccination with the live attenuated RVF Smithburn strain vaccine was investigated in two groups (Group A and B) of sheep and goats. Also, two batches (Batch I and II) of the same vaccine were used to compare between them. The IgGsandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to detect IgG antibodies in serum samples of vaccinated animals. For Batch I, the percentage of IgG positive animals significantly declined from 95% to 66.7% after the elapse of one year, and to 50% after the elapse of four years and eight months. It would decline to zero after six years and eleven months. For Batch II, the decline of the percentage of IgG positive animals from 87%, which was attained at four weeks following vaccination, to 77.3% after the elapse of one year and eight months was not significant. It could be concluded that the level of herd immunity induced by the live attenuated RVF Smithburn strain vaccine significantly declines with the elapse of years. Also, the decline of the level of herd immunity varies between different batches of the same vaccine. Hence, efficient and cost-effective vaccination strategies for control of RVF have been discussed. INTRODUCTION Herd immunity to Rift Valley fever (RVF) occurs in animals after natural infection with the RVF virus as well as after vaccination. This immunity is demonstrated by detection of antibodies to RVF virus in serum samples of infected or vaccinated animals. The ELISA technique has the advantage of differentiating between immunoglobulin M (IgM) and immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies to RVF virus (Paweska et al., 2003). Since IgM antibodies persist in the blood for 4-7 weeks following vaccination or natural infection and IgG antibodies persist for few years (Paweska et al., 2003, Elfadil et al., 2005), immunity could be monitored by detection of IgG antibodies. However, the duration of herd immunity after vaccination is variable. It has been reported that the inactivated RVF vaccine confers immunity for 612months; therefore, annual vaccination is recommended (OIE, 1996). However, conflicting reports were published about the duration of immunity after vaccination with the live attenuated RVF vaccine (Losos 1986, OIE 1996). In the regions of Jazan, Tahamat Asir, Tahamat Makkah and Albaha in Southwestern Saudi Arabia, mass vaccination with the live attenuated RVF Smithburn strain vaccine was implemented after the occurrence of RVF outbreak in 2000/2001, and vaccination of six-month-old animals has continued thereafter. However, herd immunity monitored in 2003 ranged from 16% to 30% in different districts of Jazan region (Elfadil and Ali, 2006a). Hence, the issue of mass revaccination is now under consideration. In order to implement the most efficient and cost-effective strategy to control RVF, knowledge of the duration of herd immunity in local breeds of animals in Southwestern Saudi Arabia after vaccination with the live attenuated RVF Smithburn strain vaccine is essential. This paper clarifies the duration for which IgG antibodies to RVF virus persist in the blood of sheep and goats vaccinated with different batches of the live attenuated RVF Smithburn strain vaccine and discusses the appropriate vaccination strategies that could be implemented for control of RVF. MATERIALS AND METHODS Two groups (Group A and B) of local breed sheep and goats in an experimental farm in Jizan district, Southwestern Saudi Arabia, were used to follow up the duration of IgG antibodies to RVF virus after vaccination. Each animal was marked with a numbered ear tag. Two batches (Batch I and II) of the live attenuated RVF Smithburn strain vaccine (RSA Registered No. G 0119 Onderstepoort Biological Products Ltd., South Africa) were used to allow comparison between them. The first group (Group A) consisted of 20 female sheep and goats (10 sheep and 10goats). All animals in the group were vaccinated with the live attenuated RVF Smithburn strain vaccine (Batch I) on August 2000. These animals were followed for disease signs and serologically tested to detect IgG antibodies to RVF virus on September 2000 (four weeks following vaccination), September 2001, September 2003 and April 2005. The second group (Group B) consisted of 30 female sheep and goats (8sheep and 22 goats). All animals in the group were vaccinated with the live attenuated RVF Smithburn strain vaccine (Batch II) on July 2003 (Elfadil et al., 2005). These animals were followed for disease signs and serologically tested to detect IgG antibodies to RVF virus on August 2003 (four weeks following vaccination) and April 2005. The percentage of immune animals was measured by the percentage of IgG positive serum samples in each test. The IgG-sandwich ELISA techniques used to detect IgG antibodies to RVF virus was described in previous publications (Paweska et al., 2003, Elfadil and Ali, 2006a). Statistical analysis was performed using the one-sided F-test to investigate the presence of significant differences between the percentages of immune animals in different points in time after vaccination. The intercept statistic was used to determine after how many years the level of herd immunity would decline to zero. Only data from Group A were used to determine the intercept statistic. RESULTS In Group A, the percentages of IgG positive animals were 95% in September 2000 (100% in sheep and 90% in goats), 66.6% in September 2001 (55.5% in sheep and 77.7% in goats), 64.5% in September 2003 (66.5% in sheep and 62.5% in goats) and 50% in April 2005 (33.3% in sheep and 66% in goats). The decline of the percentage of immune animals from 95% to 66.7% after the elapse of one year was significant (p-value = 0.0017). This percentage of immune animals would decline to zero after six years and eleven months. In Group B, the percentages of IgG positive animals were 87% in August 2003 (88% in sheep and 86% in goats) and 77.3% in April 2005 (57% in sheep and 89.5% in goats). The decline of the percentage of immune animals from 87% to 77.3% after the elapse of one year and eight months was not significant. DISCUSSION Knowledge of the duration of herd immunity after vaccination with the live attenuated RVF vaccine is essential in order to decide which vaccination strategy could be adopted. Different vaccination strategies to control RVF may be considered according to the situation of the disease. One strategy is mass vaccination of all livestock in an affected region, which is usually implemented to control RVF epidemics. Another strategy is partial vaccination, which is limited to young animals at the age of six months after the disappearance of maternal immunity; or ring vaccination, which is implemented at the occurred-nce of sporadic recent cases of RVF in high-risk areas (Elfadil et al., 2006b, Elfadil et al., 2006c). Partial and ring vaccination were implemented during the inter-epidemic phase of the disease. The level of herd immunity conferred by vaccination partially depends upon the type of the vaccine used. The results of this study demonstrate that there was a difference even between different batches of the same vaccine regarding the percentage of immune animals attained after four weeks following vaccination (95% for Batch I versus 87% for Batch II). Moreover, the decline of the level of herd immunity after one year was significant for Batch I (95% to 66.7%), while it was not significant even after one year and eight months for Batch II (87% to 77.3%). These findings should be considered when coming to the choice between different vaccines for control of RVF. The results of the present study demonstrate that the percentage of immune animals significantly declines with the elapse of time. These results are consistent with the findings of a previous study, which reported a significant decline of RVF neutralizing antibodies from 71.7% in 1988 to 23.9% in 1989 Thiongane et al., (1991). Also, the results are consistent with our field observa-tions on the significant decline of herd immunity in Alarda district, which is the hardest hit by the RVF outbreak in Jazan region, Saudi Arabia Elfadil et al., (2004), from 95% during the outbreak to 47% two years later Elfadil and Ali, (2006a). In field observations, the decline of herd immunity could be partly attributed to generation turn over and/or entries of new unvaccinated animals. However, in the present study the decline in the percentage of immune animals could be due to low sensitivity of the diagnostic test. It was reported that time-dependent changes in the sensitivity of ELISA were clearly evident specially for IgM-capture ELISA which was 100% sensitive 5-42 days following infection or vaccination, and only 12.5% sensitive 3 weeks later (Paweska et al., 2003). Although the results of the present study indicate a significant decline of the percentage of immune animals after one year of vaccination for Batch I of the vaccine, the decline after one year and eight months for Batch II was not significant. Also, IgG antibodies to RVF virus were detected in 64-77.3% of vaccinated animals after the elapse of 1-2 years and they were detected in 50% of vaccinated animals after the elapse of four years and eight months. Moreover, it has been proved that animals vaccinated with the live attenuated RVF vaccine were immune even after the disappearance of antibodies from their blood suggesting other mechanism of cellular immunity (Barnard, 1979). Also, it has been reported that the live vaccine induces lifelong immunity against clinical disease (OIE, 1996). Considering these findings and reports, implement-ation of mass re-vaccination to control RVF during the interepidemic phase of the disease could not be justified. Therefore, it is recommended to implement partial vaccination with the live attenuated RVF vaccine for young animals at the age of six months, and to implement ring vaccination when sporadic recent serological and/or clinical cases of RVF occur in high-risk areas. However, since the live attenuated RVF vaccine was reported to cause abortion (Morril et al., 1987), vaccination of pregnant animals should be avoided. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: We would like to thank Drs. Sami S. M. Ali, Shehta M. Musa, Khalid A. Hasab-Allah and Omer M. Dafa-Allah from Jazan Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory for performing the ELISA tests. REFERENCES 1- Barnard, B. J. H., (1979). Rift Valley fever vaccine – antibody and immune response in cattle to live and an inactivated vaccine. Journal of South Africa Veterinary Association, 50, [155-157]. 2- Elfadil, A. A., Musa S. M., Elkhamees M., Elmujalli D. and El Ahmed K., (2004). Epidemiologic study on Rift Valley fever in the South-west of Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Journal of Science and Technology, Vol. 5(1), [110-119]. 3- Elfadil, A. A., Musa S. M. and Ali S. S., (2005). Antibody response of sheep and goats in Saudi Arabia to the live attenuated Rift Valley fever vaccine. Journal of Science and Technology, Vol. 6(1), [126-133]. 4- Elfadil, A. A. and Ali S. S., (2006a). Serological survey of Rift Valley fever in Jazan region, Saudi Arabia. Journal of Science and Technology, Vol. 7(1) [5-13]. 5- Elfadil, A. A. Hasab-Alla K. A., Dafa-Alla O. M. and Elmanea A., (2006b). Persistence of Rift Valley fever in Jazan region, Saudi Arabia. Rev. Sci. Tech. Off. Int. Epiz., 25(3), (in press). 6- Elfadil, A. A., Hasab-Alla K. A. and Dafa-Alla O. M., (2006c). Factors associated with Rift Valley fever in Southwestern Saudi Arabia. Rev. Sci. Tech. Off. Int. Epiz., 25(3), (in press). 7- Losos, G. J., (1986). Rift Valley fever vaccination: in Infectious Tropical Diseases of Domestic Animals, published in association with the International Development Research Center, published in the USA by Churchill Livingstone Inc. New York, [594-595]. 8- Morril, J. C., Jennings G. B., Caplan H., Turrel M. J., Johnson A. J., and Peters C. J., (1987). Pathogenicity and immunogenicity of a mutagen-attenuated Rift Valley fever virus immungen in pregnant ewes. American Journal of Veterinary Research, 48, [1042-1047]. 9- OIE Manual (1996). Rift Valley fever. Chapter 2.1.8, 102-108. 10- Paweska, J. T., Burt F. J., Anthony F., Smith S. J., Grobbelaar A. A., Croft J. E., Ksiazek T. J. and Swanepoel R., (2003). IgG-sandwich and IgM-capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of antibody to Rift Valley fever virus in domestic ruminants. Journal of Virological Methods, November, 113 (2): [103112]. 11- Thiongane, Y., Gonzales J. P., Fati A. and Akakpo J. A., (1991). Changes of Rift Valley fever neutralizing antibody prevalence among small domestic ruminants following the 1987 outbreak in the Senegal River basin. Research in Virology, 142, [67-70].