Facilitating the learning of Chinese Grammar: A report incorporating

advertisement

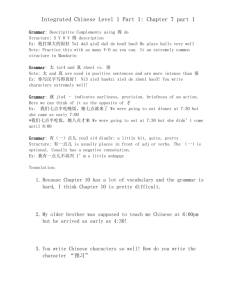

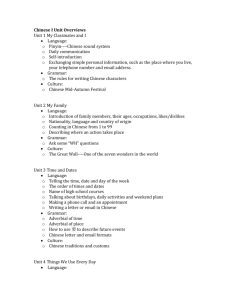

Facilitating the Learning of Chinese Grammar A report incorporating a study tour in China Xi Ping Chen Introduction It will be well understood that our first language has been acquired completely in a manner that is natural and unintentional. This does not mean that a second language can be learnt by the same means. It is in fact generally not feasible to reproduce such a situation in the classroom context. A different framework is required in which to teach the second language. The ultimate goal of teaching a second language is to assist students to gain the necessary skills in the target language so that they can communicate efficiently and effectively. Problems of second language teaching in Australia often are that: the course length is short, the weekly teaching hours are very limited, and the students usually do not have sufficient language environments in which to practise. And yet they need to meet the standard of language proficiency. This means that the teaching of grammar is essential in the second language regardless of the students’ age group. School students may not understand grammar patterns very well in their first language, and learning a second language will often help. Most of my teaching is to adult students at TAFE who are generally professionally oriented and have a clear purpose and determination in learning a second language. Their time is usually precious and focused on knowing the rules and patterns they can apply in their second language communication in their own situations. However, grammar, though necessary, is not easy to teach and many texts are somewhat theoretical, which makes it very difficult for learners to apply to their communication. For this reason I chose to investigate the best methods and practice for teaching Chinese grammar to help students grasp the Chinese language with greater ease, speed and precision. With these goals in mind I sought out expert researchers in the field and investigated participating in courses that might give me practical insights into these issues. Since I had established networking opportunities during previous visits to China I was able to make use of good contacts made. Activities in China during the study tour It was an honour for me to win the 2009 Premier’s Teacher Scholarship and I am very grateful to Kingold Group Companies Ltd who sponsored the scholarship financially. During a five week visit to China, I: ●participated in a specialist teacher’s training course at the Beijing Language University, ●observed teaching laboratories for Chinese as second language to the foreign students at both East China Normal University and Beijing Language University, ●attended the Annual Conference of Teaching Chinese as a Second Language to foreigners in Shanghai, organised by the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office of the Shanghai Municipal People’s Government (7- 8 Jan 2010), ●observed mini lectures delivered by trainee teachers and noted the feedback provided by the Beijing Language University lectures, and ●visited Beijing Language University, East China Normal University, Shanghai Normal University and Fudan University, where I was privileged to meet and have discussions with some leading experts and professors in this field. In this way I have thoroughly appreciated the valuable contributions made by Prof. Shi Jia Wei, Prof. Liu Xun, Prof. Fan Kai Tai, Prof. Shi Chun Hong, Prof. Wu Zhong Wei, and Prof. Wu Yong Yi. Some Findings Chinese grammar teaching can be divided into three stages: primary, intermediate, and advanced. For each of these stages the learning strategy should be distinct. For school and college students, the primary and intermediate stages are most relevant. Chinese is a distinct language not only because of its own character writing system, but also because Chinese grammar is very different from English or other European languages. What should be taught in Chinese grammar? Clearly when the sentence structure is the same as it is in English, such as the general sentence pattern “S-V- O” there is no problem for English speaking students. However, there are other Chinese sentence structures that are very different from English, so the grammar needs to be precisely and thoroughly explained. Sometimes the differences can be very subtle. For example, in English one says, “I am twenty-one”, where in Chinese it would be said, “I twenty-one years old.” The sentence does not require the verb ‘to be’. Another example: in English people say: “I am very well.” In Chinese people would say: “I very well.” The enunciated rule becomes, ‘after the subject we do not need to put the verb ‘to be’ if it is followed by a number or an adjective’. For these kinds of difference between the target language and the mother language it is best for the teacher to explain at the beginning when a new sentence structure is introduced, and then to give students sufficient exercises so that they identify both the new pattern (the rules) and its logic. In allowing the students to realise or notice such similarities and differences between the target language and their mother tongue they will often gain a sense of achievement which in turn increases the enthusiasm for learning. Ways of Introducing Grammar How should a new grammar be introduced to students? Choosing from among many those which are appropriate for the particular grammar points can save much time and achieve good results. Various impressive techniques have been developed in China in using boards enabling rapid visualisation of language patterns by the learner. In such cases the learning is more precise and it also makes the learner feel that learning Chinese is enjoyable and interesting, and consequently generates enthusiasm. Commonly used methods in China are: a) Introduce a new grammar by simply using the sentence patterns (drills) directly from the text. Families of examples clearly demonstrating the grammar point will be found for each lesson. It is a rapid and easy technique for simple sentences and the teacher has only to pick up the text and verbally explain the meaning and usage. Mostly, there will also be exercises included with the lesson. b) The teacher could create a more visual situation where students should be able to clearly understand the teacher’s purpose. The teacher should prepare students for the new grammar, e.g. first learn new vocabulary. It may then involve some role play using the target language instead of speaking their mother tongue, e.g. a teacher might use a box of chocolates to teach the ‘ba’ sentence: Wǒ bǎ qiǎokèlì cóng bāoli ná chūlái le. (I have taken the chocolate out of my bag.) Wǒ bǎ qiǎokèlì fàngzài zhuōzi shang. (I have put the chocolate on the table.) Wǒ bǎ qiǎokèlì dǎkāi le. (I have opened the box of chocolate.) Wǒ bǎ qiǎokèlì fàng zài zuǐli. (I have put the chocolate into my mouth.) Wǒ bǎ qiǎokèlì chīle. (I have eaten the chocolate). Through the teacher’s simple role play the students understand and memorise the sentence drill easily, and by the time the exercise is finished, students have eaten the box of chocolates and also learnt the grammar in a relaxed and enjoyable manner. c) When introducing a new grammar rule it is always important to review the prior knowledge and then use this as a staging point to the new concept. Learning a language is a vertical spiral process of establishing a basic knowledge, exercising a variety of applications and then advancing to a new level where the cycle is repeated. The teacher needs to be creative in devising various exercises so that students can master their pre-existing knowledge even better, and also gain the new grammar easily. In one typical example here, the teacher first revises with students the following verbs which indicate a direction which the students have already learnt previously: shàng go up xià go down jìn to enter chū to exit lái (to come) qù (to go) At this point the teacher introduces a new grammar which combines these kinds of verbs together to give a new meaning: shàng go up xià go down jìn to enter chū to exit lái (to come) shàng lái come up xià lái come down jìn lái come in chū lái come out qù (to go) shàng qù go up xià qù go down jìn qù go in chū qù go out Using such a tabular display will encourage students to easily find the pattern by themselves and to remain alert to additional of such applications. It can save much verbal explanation by the teacher which could otherwise overwhelm. This type of vocabulary has the advantage of being visually illustrated instead of using English to explain. In the classrooms at the universities in Beijing and Shanghai they all only speak Chinese which is good for training students’ listening skills. (Note that the Chinese second language students there come from a spectrum of nationalities.) d) Using a comparison method to introduce a new grammar is also very effective. There are two different types of comparisons: 1. Compare the difference between the target and the first language: In English we say: “I work in the city.” where in Chinese we say: 我 在市里工作。 (Wǒ zài shìli gōngzuò. meaning: ‘I in the city work.’) In English we say: “Last week I worked in Telstra.” In Chinese we say: 上个星期我在 Telstra 工作。(Shàng ge xīngqī wǒ zài Telstra gōngzuò. Meaning ‘Last week I in Telstra work.’) 2. Compare the similar words in the target language where it is difficult for a learner to sense the difference in usage: “yǒudiǎnr” meaning ‘a little bit’ and “bǐjiào” meaning ‘comparatively’. Both words are adverbs and can be followed by an adjective. However, ‘yǒudiǎnr’ is used solely for things that are not good, or not liked whereas ‘bǐjiào’ can be used for either, e.g. guì 贵 expensive piányi 便宜 inexpensive yǒudiǎnr 有点儿 A little bit Zhèr de dōngxi yǒudiǎnr guì. 这儿的东西有点儿贵。 The goods here are a bit expensive. (One never says ‘the goods here are a little bit inexpensive’) bǐjiào 比较 comparatively Zhèr de dōngxi bǐjiào guì. 这儿的东西比较贵。 The goods here are quite expensive. Zhèr de dōngxi bǐjiào piányi. 这儿的东西比较便宜。 The goods here are quite inexpensive. For such grammar points using a comparison method would be more appropriate. Each of these suggested methods can be used blended, or one method may be more suitable for a particular grammar point. If the teacher is only using the target language in the teaching process, it becomes critical that they have sufficient breath of knowledge and adequate skill to engage student learning with greater efficiency. Theoretical Grammar and Classroom Grammar Theoretical grammar is considerably more complex than the classroom grammar. Mr Xu Guo Zhang, a noted linguist in China, gave his definition (1991) of the distinction between linguistic grammar and classroom grammar as follows: Linguistic grammar is the research into the symmetric rules in the language while classroom grammar is the concentration on its use as a tool to master the language. Theoretical grammar therefore tends to focus on the higher level theory using various technical terms and jargon. Quite often such terminology is difficult for a non linguistic person to comprehend and, in fact, can become a stumbling block to learning the language. The learner may imagine that he/ she has to understand the finesse of linguistic structures before acquiring basic language and may therefore feel overwhelmed and demotivated. It can sometimes also be an unwitting trap for teachers in their fervent desire to explain structure. Although research into the rules of the language system is desirable, students need to be confronted with only the minimum of complexity. A ‘simple’ example can provide an illustration. The word “le” in Chinese has many meanings when it appears in different positions in a sentence. In Chinese grammar it can be summarised as in ‘le1’, ‘le2’, ‘le3’ and ‘le4’. This is the most commonly used word in Chinese, and yet it is very difficult for a second language learner to use it correctly. Of the four types, one only needs to teach “le1” and “le2” to the beginners and intermediate learners, and, even then, only in isolation. As Prof Fan Kai Tai emphasised to me, “The teacher must have a bucket of water but only needs to give the students one cup at a time,” meaning that the teacher must know their subject thoroughly, precisely and deeply, while presenting it in a measured way. Language acquisition Whether the ‘teaching’ is successful or not depends on how well the learners will ‘acquire’ the second language. In recent years Chinese academics have recognised the importance of studying such learner acquisition and it is now a fundamental research topic in the area of teaching Chinese as a second language. There are many scholars that focus on the learner’s ‘acquisition’, and there are many journals, books and publications in this field. As Prof. Liu Xun also said, whether the teaching is successful or not is determined by the learning. The understanding of the learner’s acquisition is the fundamental basis of studying teaching. This is a significant change from the past ‘teacher oriented’ learning and this is also reflected in grammar teaching. A classic example of how a complex concept can be simplified follows: A ‘ba’ sentence is a special pattern in Chinese which does not have an equivalent expression in English. It is not only hard for students to learn, it is also hard for the teacher to explain as it has so many usages in different scenarios, in all 16 different ‘ba’ sentences as enumerated by one Chinese professor. The authors Liu Yue Hua, Pan Wen Yu, Gu Wei in their book ”Practical Modern Chinese Grammar” fill 20 pages explaining the ‘ba’ sentence. (This is regarded as the best grammar book for Chinese as a second language for teachers and learners.) However, very recently Professor Shi Chun Hong at the Beijing Language University has made teaching and learning of this aspect significantly simpler by creating the following revolutionary technique. The normal sentence structure is: Subject followed by a verb and then the object. Using a “ba” sentence will enable the moving of an object before the verb in order to emphasise the change of the object as a result of the verb. The subject ‘A’ takes an action (verb) towards the object ‘B’ so that the object has changed, resulting in ‘C’. He splits the ‘ba’ sentences into two separate sentences: 1. “Subject followed by a verb and then object” which every student can see and understand without any difficulties. 2. “Object has changed as the result of a verb” which Chinese normally do not say in that way, but is purely to assist the learner to see the pattern as to how the “ba” sentence is structured. Firstly the teacher should introduce the specific pattern of the ‘ba’ sentence: A (subject) + ba + B (object) + verb + C (result) Then illustrate the following examples: 1. Wǒ chī fàn. I eat rice. Wǒ bǎ fàn chī wán le. I have eaten (all) the rice. 1. Wǒ huàn Měiyuán. I change US dollar. 2. Měiyuán huàn chéng Rénmínbì. US dollar is changed into RMB (Chinese Yuan). Wǒ bǎ Měiyuán huàn chéng Rénmínbì. I change US dollar into RMB (Chinese Yuan). 1. Wǒ zuò zuòyè. I do homework. 2. Fàn chī wán le. The rice is eaten (no more rice left). 2. Zuòyè zuò wán le. Homework is done. Wǒ bǎ zuòyè zuò wán le. I have done the homework. By giving students a number of examples they should recognise the pattern easily by themselves. I have successfully used this method many times in the classroom already. It does not require the teacher to do too much explanation as the students can easily see the pattern. The teacher can then give some further exercises to allow students to construct their own sentences to demonstrate understanding and ability to use this ‘ba’ sentence. Most importantly, at this stage the teacher must give students the rules where this ‘ba’ sentence can or cannot be used. Again, it is suggested that a list of the examples be given to support the rules. ‘Ba’ sentences are often used in the situation when things are ‘away’ from you, i.e. things which one has lost, but not used for things one has gained. Wǒ shū le wǔ wàn yuán. I lost fifty thousand dollars. Wǒ yíng le wǔ wàn yuán. I won fifty thousand dollars. Both sentences are correct in Chinese; however only one can be changed into a ‘ba’ sentence. We can say: “Wǒ bǎ wǔ wàn yuán shū le.” (lost fifty thousand dollars) But we never say: “Wǒ bǎ wǔ wàn yuán yíng le.” (gained fifty thousand dollars) Prof Shi has also said, “There are always exceptions to any grammar rules. However, there are always rules for any exceptions.” Teachers should avoid saying “We Chinese say it in this way” without giving explanations. This is not going to help students to learn. Prof. Shi has not yet published his research so I felt very privileged to have him explain it to me. He uses similar techniques to simplify many other difficult grammar points. Class Time Management The trend in teaching grammar has gradually changed and the current “best practice” it is said to be a process called “jīng jiǎng duō liàn”. What “Jīng” means precise, “jiǎng” means the teacher talks. Thus “Jīng jiǎng” indicates that the teacher should “say less but more precisely” in the classroom. However, the teacher will need to explicitly explain the rules and conditions when learning a new grammar avoiding unnecessary confusion, misunderstanding or the common errors of second language learners. It has become the common golden rule that the time ratio between the explanation of the new grammar by the teachers and the exercises by the students should be about 30 percent to 70 percent. (In the old ‘duck feeding’ method the teacher used to dominate the class for most of the time.) The teacher needs to create a variety of methods to give students an abundance of practice and exercise. Clearly, no language can be learnt merely by listening to the teacher’s talking. There are many useful techniques available to give students practice, such as simple mechanical imitation using sentence drills, setting up a role play situation or via a translation, cloze technique, questions and answers, re-telling stories and so on. Developments in Chinese as a Second Language Teaching Chinese as a second language commenced at the beginning of the 1950’s, soon after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China. It has continued to develop very quickly, particularly in the last 20 years. The Chinese government recognises the importance of teaching Chinese as a second language nationally and internationally and the government has even set up an office, ‘The Chinese Language Council International’ to promote Chinese language teaching. The Department of Education in China considers that this is a “country and nation’s business”. While 20 years ago there were only about 20 universities which had Chinese as a subject, now over 300 universities in China offer it. A large group of academics is involved in creating the standard syllabi, publishing new text books, setting up standard assessment materials, and continuing research. These resources have been spread all over the world and, as the importance of China’s influence increases internationally, Chinese as a second language teaching will develop even faster. Language in general develops alongside technical advancement and social and political movements. In China there were several periods where the Chinese language developed dramatically, for example, after the 4th May Youth Movement in 1919, the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the Cultural Revolution from 1966 and the current, so called “New Era” from 1978 onwards. A vast number of new words and expressions were created during each of these periods. Statistics show that currently there is an average of about 1000 new words being created each year reflecting the movements in the society, the changes in economics and the development in technology. Some examples: “Diànnǎo” (computer), “shǒujī” (mobile phone), “kǎlā OK” (Karaoke) and so on. The earlier (1950s) texts from Peking University were based mostly on covering grammar points. Texts from Beijing Language University followed the same pattern for decades, covering about 200 grammar points according to Prof Fan Kai Tai. Texts were written in a formalised manner of choosing the grammar points per lesson with the corresponding rigid design of dialogue and exercises. It became obvious to Chinese academics that this method was somewhat artificial and not universally applicable, with the result that text books have improved dramatically in more recent years. It was acknowledged that other languages have sufficient of their own distinctive characteristics, grammar, and different cultural backgrounds to warrant the writing of separate texts aimed at accommodating these differences. The outcomes of this debate will be demonstrated through texts appropriate for different foreign languages and cultures over the years to come. Conclusion The process of attending specific lecture series, participating in analysis seminars, and the opportunity of having one to one discussions with experts in the field in Beijing and Shanghai, have provided me with a most wonderful spectrum of new ideas, and a consolidation of existing thoughts ready for integration with previously known working practices regarding: the recognition of underlying learner attitudes and capacities, The employment of clear simple mental images for the visualisation of grammar patterns, and a greater awareness of the potential benefits of constructive teacher - learner interactions. As it is ultimately the learner who adopts the second language it is their mental processes that are of paramount importance. Hence the development of a meaningful teacher-learner relationship is of greater value than seeking a formulaic solution in language teaching. Nevertheless there are many techniques for making language perception easier for the learner regardless of age. Some of these have been discussed and more still are yet to be evolved. Since every class is likely to have a broad spectrum of learners, a diversity of techniques will still need to be used to cater for the range of individuals. Teachers will therefore need to be selective and creative in applying these to their particular situations. For me it has been a wonderful opportunity and an exciting revelation to hear first hand of the innovations made in Chinese grammar teaching and to successfully test these in my own classes.