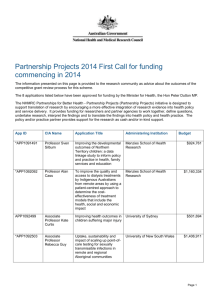

Transcript of interview with Fiona Stanley

advertisement

Transcript of interview with Professor Fiona Stanley Voice-over: Welcome to the National Health and Medical Research Council podcast series, a conversation with some of the great minds and leaders in Australian medical research. The NHMRC is Australia's leading funding body for health and medical research. We provide the government, health professionals and the community with expert and independent advice on a range of issues that directly affect the health and wellbeing of Australians. Interviewer: Professor Fiona Stanley is the founding director of the Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, which was established in Perth in Western Australia in 1990. The institute is multidisciplinary and researches prevention of major childhood illnesses. It currently has more than 400 staff and students. In addition to this role, she is a professor in the school of paediatrics and child health at the University of Western Australia. Professor Stanley has many awards and accolades, including being named Australian of the Year in 2003, and in 2004 she was honoured as a national living treasure by the National Trust. She's also the Unicef Australian Ambassador for Early Childhood Development. Two of Fiona Stanley's most significant discoveries are that a maternal diet rich in folic acid can prevent spina bifida in babies and that cerebral palsy is not only the result of birth trauma, but may also be caused by other factors, including infections or blood incompatibilities. She's also recognised for her considerable contribution to Aboriginal maternal and child health in Western Australia. Fiona, thanks very much for joining us today on this National Health and Medical Research Council podcast, a bit of a pioneering podcast in the series, because this one's being done over Skype. But welcome. Prof. Stanley: Thank you very much. Interviewer: I thought we might begin by you giving us an overview of this wonderful institute, the Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, which you were the founding director of and which was established in 1990. You've done some terrific work over the years. I thought you could give us a bit of a helicopter view. Prof. Stanley: Yes. Well, the interesting thing about the institute is that we really established it because I had come out of a - every 10 years I seem to have a frustration in my career. After the first 10 years of clinical work I realised that I wasn't going to make it as a clinician and that I really wanted to get into epidemiology and preventive medicine. So for 10 years I was in an NHMRC-funded unit in epidemiology and preventive medicine. After 10 years of that, I thought, 'Uh-huh, epidemiology alone can't unpack the complex causal pathways to child health problems. We need a multidisciplinary institute that is able to go from what's happening in genes and cells and molecules to the whole child and then to the child in its family and its community, so right through to the population sciences, and they all need to be together in one building and they all need to interact and work together in a lovely collaboration which will really start to understand cause and prevention,' and that was the dream of the institute. Of course, when you set up an institute in a remote place like Perth, a lot of what you do is opportunistic rather than strategic. So in the first 10 years or so, we were opportunistic, and we were luckily so. In other words, whilst the people that I managed to recruit in the institute were 1 nearby, and therefore achieving - that we could actually get them in here - they were the right kinds of people. So we had the immunology research group at the Children's Hospital, who were basically mucosal immunologists, looking at what would happen to the developing respiratory tree; they've unpacked the asthma epidemic, which has just been fantastic, and have moved from about 80 per cent of their work being in animal models now to about 80 per cent of their work being in the human model, including our big cohort studies that we do here in Western Australia. There was a group around - and that's the group around Pat Holt and Wayne Thomas. Then there's another group around childhood leukaemias and cancers, including solid tumours, around Ursula Kees. She was also in the immunology research unit. She's expanded dramatically and has built upon growing these tumours, both leukaemias and spotted tumours up as cell lines, which now go all over the world, and to look at both the genetic and immunological aspects of cancer. We've linked that into the population sciences, where we have a big group now working in childhood cancers, the genealogy of childhood cancers. So those two groups in basic science moved their mostly immunogenetic basic science research into the institute, and we've expanded that just recently by recruiting Jenny Blackwall from Cambridge. She is really a molecular parasitologist, looking at the sort of genetic aspects of infectious disease. And we also have Pru Hart now who heads up an inflammation laboratory particularly looking at skin. And then we recruited from Melbourne a top clinical researcher, Peter Sly, whose responsibility it was to work in mainly respiratory disease, but to build up clinical research in the institute. And then, of course, my group expanded dramatically from just a fairly narrow immunological maternal and child health group and focusing a lot on peri-natal epidemiology - things like low birth weight, birth defects, cerebral palsies, neurodevelopmental disorders. It's expanded enormously into psycho-social pathways, suicide prevention, mental health, Aboriginal child health, infectious disease, and a much expanded developmental disorders research endeavour. So the plan of the institute was to try and say well, okay, we've got these major different groups the basic scientists, you know, including geneticists and info - biomathematicians and so on, the clinical scientists and the population scientists, but what we want to do is have big important themes going across the entity. So asthma allergy is one theme, cancer is another theme, infectious disease is another theme, Aboriginal child health another theme, mental health and developmental disorders, and actually sort of child health and development normal pathways into child health and development, and the whole idea was to have basic clinical and population sciences represented in all those themes. That's not happened yet, 17 years down the track, but it has happened a lot more than you would think. So this idea of having true collaboration across disciplines has been fantastic, particularly in asthma allergy, particularly in the cancer, particularly in some of the infectious disease program, less so in things like Aboriginal health, mental health and developmental disorders. We don't have a basic science underpinning for those, and I think we'd have to make a major investment and recruit some top people to make that an effective collaboration. The other big thing that the institute does is not just sit around and publish and try and publish in the best journals and hope that it gets picked up. What we do is have a big translational capacity. So a lot of my time and the time of some of the people in all of the different groups, but particularly in the clinical and in the population sciences, is about influencing policy or clinical practice or population health practice, which has been incredibly successful, but also the basic sciences had a very big success rate in terms of commercialisation. 2 So we've now got several companies - and many, many patents - that the institute has produced. So I guess it's a wonderful hotch-potch of, you know, science trying to make a difference, focusing mostly on children and young people, but expanding a lot now beyond health even to take on board education, child abuse and neglect, and juvenile justice issues as well. So it's a pretty exciting place to be in. Interviewer: Absolutely, and world recognised for the contributions that it's made. Prof. Stanley: It's still got a long way to go, I think, in terms of world recognition as an institute, but certainly in some of these programs we've done there's international recognition. But I think as an institute at the moment we're not there. We've got quite a way to go. Interviewer: Can we drill down on some of those key achievements that you mentioned. There were lots that rang bells, but the one that I thought was pretty interesting was asthma. You said you'd moved out of mice and into people, or you'd developed a major understanding in, I guess, the basis of asthma and what causes it and possibly how to treat it. Could you just expand on that? Prof. Stanley: Yes, I think it's been a really exciting road for Pat Holt and Wayne, initially Geoff Stewart as well, who has since moved down to the university, and the close collaboration and why it's been so successful is two major reasons: one is that Peter Sly, who we recruited as our clinical scientist, has had a very strong collaboration with Pat looking at the clinical aspect; the other thing has been the very good population data, particularly the cohort data that we have in the institute. We have a couple of very good longitudinal studies which have enabled them to look at both the genotype and the phenotype, and how the allergy phenotype in terms of cytokines and immune, as well as the clinical pattern, has a task. I think these guys, in collaboration with two or three other groups around the world, have actually rewritten the asthma story, and really have pointed out how important the early immune responses to inhaled allergens and trying to unpack why, in those either genetically at high risk with a very strong family history of asthma, or the others, why these pathways are particularly positive or negative in terms of the final phenotype. So that's led them on to, in the sort of last two years, to apply for an FDA-approved NIH trial to actually look and see if they can't intervene in the first two years of life. It's going to be a major well, it's actually commenced as a major randomised trial in five centres internationally to see if they can't start giving drugs that are currently used, actually, for asthma later on, to actually see if they can make a difference in the early years and to actually try and prevent asthma in those high-risk cohorts. Interviewer: I seem to understand or remember that there's often a geographic distribution in the susceptibility of populations to asthma; is that correct? Prof. Stanley: Well, yes, and a lot of that was beginning to be explained by the hygiene hypothesis, which Pat wrote a lot about earlier on, that the differences between East and West Germany, for example, which were unexpectedly lower rates in East Germany, in spite of air pollution and other things compared with West Germany, and they put this down to the fact that the kids in the east were in dirty surroundings, which meant that their immune systems were fighting infections rather than just hanging around, you know, inappropriately responding to inhaled allergens. So that kind of explanation holds true, actually, for Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal populations - there's a higher rate of asthma - sorry, lower rates of asthma as you 3 go more remotely in Aboriginal communities. We found that in the Aboriginal child health survey. So, yes, I think there is probably some underlying complex interaction between early infection and asthma, although it's certainly not as clear as Pat originally thought, and one of the asthma cohort studies that we've done in fact did not confirm that early and repeated infections were protective against asthma. So I think it is more complex as to how - because, of course, what is asthma and how you diagnose wheezing at various stages is very much more complex, and there are going to be children who wheeze because they have small airways, either because they were exposed to smoke in utero, or from viral infections, and that's a different kind of wheezing than the allergic wheeze, which is a different pattern. So it's very important that we work out these different phenotypes and how we're going to - you know, because they are different, obviously, both in terms of genetic predisposition and in terms of environmental exposures. Interviewer: Now, in this podcast interview, one that we've done previously was with Professor Caroline McMillen from the University of South Australia, who I'm sure you know -Prof. Stanley: Yes. Interviewer: And she was talking about - I guess we were talking really about epigenetic factors that were occurring in utero. Is asthma in any way linked to potential epigenetic modifications that occur in utero? Prof. Stanley: That's a very good yes. You should ask Pat this. I mean, that actually is a very good question. It's quite likely that it could be. I mean, I think that now epidemiologists, which is what I am, have to become very much more knowledgeable about these issues. We're more interested in the epigenetic patterning in relation to child development, and how social exposures, both in utero and even subsequently, mediated perhaps through stress pathways, can permanently change the genotype. That's very much where my very poor knowledge on this is playing a role. For example, there's just been a working party of the PMSEIC looking at possible epigenetic influences on the pattern of Aboriginal child development in terms of the metabolic syndrome and how maternal stress in utero may well be something that turns on genes or influences the genotype, and I think it starts to explain some of the social patterns that we see in epidemiology, because it is actually - I mean, there are social gradients in many diseases which are quite difficult to explain. That's what the actual underlying biological mechanisms might be, and epigenetics, I think, is going to help us solve some of those. But I'm not as knowledgeable about this certainly as Caroline, but I think the whole developmental origins of health and disease, a lot of that is going to be, or needs to have, an epigenetic kind of thinking brought to it. Interviewer: That's certainly what came out of that particular discussion that we had. Prof. Stanley: I think it's very exciting. Interviewer: I point listeners to this podcast back to that one if they want to delve into that. Now we could turn now to work being done in cancer. One of the things that you've done is been able to increase the survival rates for children with leukaemia - and you mentioned some of the work you were doing on cancer before. So what are some of the key highlights from that? Prof. Stanley: Well, Ursula Kees heads up our cancer laboratory, and Liz Milne heads up our epidemiology cancer childhood, cancer epidemiology, and in fact has just been made Australia's rep on a new international network of childhood epidemiology of childhood cancers, particularly 4 starting to look at some of the rare cancers which are very difficult to look at when you're just in one country with fairly low numbers. So that's pretty exciting. Some of these rare cancers we've been able to have a look at internationally. The major work that Ursula - well, Ursula is now in two major areas. One is the leukaemias have started now a major program in brain tumours. And in fact the epidemiological work is also mirroring that. So Ursula's main, exciting discovery has been on a particular translocated oncogene. Interviewer: Just for our general listeners, what is an oncogene? Prof. Stanley: Well, this is a gene that appears to be one of the initiating factors to turn a cancer cell from being a normal cell into being one that divides rapidly without control. And whilst she is more knowledgeable about this than I - and I'm sure I'm putting it in a very simplistic way you can have genes that obviously inhibit the process and genes that promote it. And so I think that when you look at some of these genes, what she's looked at is the genetic make-up of some of these aggressive cancer cells and found that there are some that have these similar translocations. Basically she's investigated this particular one, which now looks as though, because it gives such a very bad prognosis in the children if they have this particular translocation, and she's now looking at this in terms of it being developed into a major test. It changes the treatment that these children have. So if you have this particular translocation you will go on to a much more aggressive chemotherapy than if you don't have it, where you don't need to be treated so aggressively. And it explains recurrence or relapse in some of the children with acute leukaemia. Now the reason why she's been able to do this work in the little old isolated Perth is because we were the first group in Australia to be linked up to the Children's Oncology Group, which is an international network of cancer wards, of oncology wards, clinical wards, and laboratories that are looking at it. So we were part of that - it's mostly in North America, but it includes some of the Canadian groups as well. So all of the research that's done in our centre is linked in with international, both clinical and laboratory research, so that all of the children, for example, in our oncology ward here at the Children's Hospital are part of an international randomised trial of new therapies et cetera. So that's one immediate clinical spin-off of us being a member of this Children's Oncology Group. But it means also we don't have to work with just the 18 to 21 acute leukaemias that get diagnosed in Western Australia every year - we've got 12,000 acute leukaemias that Ursula can then put a proposal up to COG and it will get looked at in terms of how much the other cancers in the other centres also have this translocation and whether it is likely to be a useful clinical tool. What she's also done is participated in the epidemiological studies, which are national case control studies, which Liz Milne is the chief investigator on, with people also from all of the other states, coordinating a national case control study looking at the aetiology of common acute leukaemia in childhood and looking at brain tumours - and these are both NHMRC funded by the way. This is because we had a kind of chance finding that women who reported taking folate in their pregnancy seemed to have a very much reduced risk of acute leukaemia in their offspring, so we decided we would do a very large confirmatory epidemiological, genetic epidemiological study, looking at all the cases of acute leukaemia in Australia and all of the cases of brain tumours - that was added on later on - and a group of controls and look at all of the antecedent data that we could. So it was looking particularly at maternal diet, but also looking at genetic markers and other aspects of exposure, such as occupational exposures, environmental exposures and so on, to really start to unpack what might be some of the causes of these still very costly and nasty cancers, particularly brain tumours, but also the leukaemias. 5 Interviewer: You mentioned folate, which is an interesting segue into some of your own recognised work. Would you like to just talk a little bit about that story for a moment? I think some of the listeners might find that particularly interesting. Prof. Stanley: Well, it's a nice story, because it's virtually - well, not quite at the end, but I think we're not at the stage where we can say we'll just keep monitoring and hope that it has a good outcome. This started way back in the 1980s, the early '80s, where I had come back from overseas very well trained and interested in setting up registers for childhood disorders, particularly registers of birth defects, cerebral palsy and intellectual disability. Of course, I always thought that it was most important that we go for the most interesting hypothesis, so all of our research is addressed to what's the next important question we need to address. The question in the 1980s, because neural tube defects, which are spina bifida and related defects, very nasty defects which kill half of the children who are born with them and the others have lifelong handicaps, which means they are completely paralysed below the lesion and their brains are often affected so they're often intellectually disabled and epileptic as well. These are very nasty defects. The big debate was, you know, there seems to be this geographic variation, is it something to do with social class? Yes, it is. Is it something to do with nutrition? Maybe. And so we decided - Carol Bower, who was my PhD student, and I set out to do one of the studies internationally unpacking whether the maternal diet, particularly focusing on vitamin intake, was an important risk factor or protective factor for neural tube defects. And I was quite sceptical. I thought all Australian women ate Vegemite and there wouldn't be an effect of folate, which is found in Vegemite and leafy green vegetables and other things that are good for you, but we found an enormous impact, a highly protective odds ratio for those mothers who reported having a diet rich in folate around the time of conception and in very early pregnancy. The neural tube closes very early in pregnancy. By the time you know you're pregnant, the neural tube has either closed or it hasn't, and you've got spina bifida. And this is occurring at around 3 per 1,000 live births in Australia. It wasn't as high as in some other places, which had poorer circumstances. So it was a very, very resounding support for the international research going on in terms of both cohort studies and case control studies - there were about 20 of them all of which supported either folate supplementation, or ours was the only one that looked at dietary folate. So that was very important support. We then all participated in the randomised control trials, which clinched it, really, to show that giving folate before pregnancy reduced the incidence of neural tube defects by 70 per cent in those that had the folate compared with those who had no folate. And so we then in Western Australia took this information in the early '90s and implemented the world's first preventive program to encourage women, all child-bearing age women, to eat more folate and to have a diet rich in folate, because you have to tell women before they become pregnant. That was the challenge. You can't wait till they become pregnant and then put them on folate, because then it's too late. So it was quite a challenge. And we set up the program in Western Australia, which we did, actually - it wasn't a Health Department program. They funded it, but we actually implemented it and evaluated it, and showed that in fact there was only a 30 per cent to 40 per cent reduction in neural tube defects and that women who were at high risk, such as Aboriginal women, young women, unplanned pregnancies, smokers and poorly educated women, didn't have any improvement in their folate intake at all, and no improvement in their neural tube defect incident rates. And those data were very important in convincing, eventually, only this year, I'm afraid, it took us seven years, to convince the Federal Government and its 6 advisory groups to actually put folate in the flour in a mandatory way. It's interesting that the food companies - a bit like the tobacco lobby - lobbied very vigorously to stop us doing this. Interviewer: Why do they do that? Prof. Stanley: They don't like being controlled. It's interesting - in the other countries they didn't. In Australia and New Zealand they were very much against it, and I just can't understand it myself, because it's a good news story for them. See, they like making folate breads, healthy breads for pregnant women and marketing them as such. Maybe we were taking away their market share, as it were. But we can't understand why it wasn't a good news story for them. But they were very, very against it. And that occurred this year. So now what we have to do is just monitor the impact of the fortification. Interviewer: It's terrific. Prof. Stanley: It's been terrific - lovely story. I mean, Carol Bower has been working on it ever since she did her PhD and now she's just turned 60 last week and is looking back on a career which has made a huge difference to babies with birth defects. Interviewer: Absolutely - a major impact. Just change the conversation a little bit. You mentioned that you'd had some commercialisation outcomes, which is always good to hear from a research institute like yours, which has such breadth of activity. You were talking before about the leukaemia and cancer research. I know that one of those spinout companies, called Phylogica, came out of your institute, and it's now listed, I believe, on the Australian Stock Exchange? Prof. Stanley: That's right, yes. Interviewer: Has that been the most significant commercial outcome from the institute, or do you have a steady stream of activity? Prof. Stanley: We've had a pretty good stream of activity, but it's been the one we've gone farthest with, as it were, and following out of Phylogica's success, we've now got a drug discovery lab in the institute, which has basically got mostly Phylogica people in it. But there's been a really good - we've had a very good relationship with big pharma, some of which has just been, 'Here's the money. We're interested in anything you produce.' That's a very good relation that Pat Holt has had with GlaxoSmithKline. We've had a lot of funding from the big pharmaceutical companies that make vaccines - we've had about, oh, probably 80 vaccine trials since the 1990s, where we've done everything from the evaluation of new vaccines to looking at whether the vaccines can be given together, to look at novel ways of delivery of vaccine. We're doing trials on HPV as well as bird flu - you know, it's huge. Peter Richmond heads up a lot of that, but we always try to add some scientific questions to our vaccine trials. Wayne Thomas has had some very successful allergy patents - in fact, the first royalty cheque, of a very small amount, was Wayne's, which came into the institute some years ago, and that was with ALK and the patent has since been sold on. So that's really for the treatment of people with allergy, because we have so many allergens that have been purified and can be used, not just house dust mite, but others. 7 And the other area has been in - Peter Sly and his team have developed novel ways of assessing infant lung function, because you can't say to a six-month-old, 'Take a nice big breath and then breathe out.' So he's got this very special mechanism of measuring lung function. And Paul Watt, who actually started Phylogica, the anti-inflammatory protein that - the molecule that we've got, he also developed a very nifty little spinhaler to enhance delivery of treatments for both asthma and pneumonia for kids, young kids, to make it sort of easy for them to take their medication. But Phylogica has been our most successful commercialisation, because it's really gone into a company and something the institute has had a very much greater role in, and Bruce McHarrie, who is our chief financial officer, as well as Paul, the director of Phylogica, have to take a lot of the credit for that and we're very proud that it's done it, because we do want to have - we want all of our - we want to have our institute successful in all areas of endeavour. Many people think because we're such advocates for Aboriginal health and for social justice and for child development, people forget that we also have this commercial success, which I'm very proud of. Interviewer: No, it's been terrific. I think there's a lot of institutes that could learn from your model. Prof. Stanley: Well, it's terrific. I think the anti-inflammatory molecule that Paul is working on, it might have some quite interesting and broad applications. It really is aimed at preventing the damaging apoctosis, you know, secondary cell death. So we're working in fact with Fiona Wood, with some of her burns. We're looking at whether it might be helpful in arthritis, and in strokes where, of course, a lot of damage is secondary neuronal death. And so it is quite an exciting stage. Now I'm not up to the minute with what's been happening lately in the science, but my sense is that it's going very well. Interviewer: Excellent. Now I guess the National Health and Medical Research Council has played a pretty big role in your career and that of the life of the institute? Prof. Stanley: Well, I think it's hugely important. First of all, I was one of the first - I think Bruce Armstrong was the first and I was the second - NHMRC fellow in clinical sciences to train overseas in - they were trying to push epidemiology because there was hardly any epidemiology going on in Australia, so I was lucky to get one of these early fellowships to train at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. I did the MSc there. Then we had two years overseas and then one year back. So I had time at the London School of Hygiene doing their course, epidemiology statistics, public health, social medicine, and then I had a year doing my thesis at the national institutes of health, child health, human development, in Washington, in Bethesda, and then the year back in Australia was terrific because they gave us the princely sum of $4,000 to set up our research, which actually meant that I could establish the cerebral palsy register, which then led to the establishment of the birth defects register, and away we went. So what that initial training did for me was to introduce me to the NHMRC really. I should probably have applied for a fellowship, but I didn't really know that I could do that, and I went into the Health Department for two years, but that was very helpful, because I set up all my databases and started record linkage, which has been a mainstay of the population health sciences of the institute - it's been the incredible databases we have here in Western Australia, which are based on the total population, and that's been absolutely wonderful. And then, of course, I was for 10 years in the NHMRC unit as a deputy director and then the director of the unit in epidemiology and preventive medicine and Bruce Armstrong was a 8 director of that until he left and then I took over the directorship until we set up the institute. So that was core funded by NHMRC to really encourage epidemiology - it meant that we couldn't apply for any other NHMRC funds, but we got lots of funds from other places, including NIH funding at that stage to keep our research going. And that grew very, very rapidly. And that's really what developed my group, and my whole maternal and child health epidemiology group was funded from that NHMRC core grant. It was just brilliant. Then when we moved into the institute, most of us, the senior scientists - about 10 of the senior scientists - got NHMRC fellowship funding. I had to relinquish mine, of course, to be the director of the institute, but everyone else - several of them are now senior principal research fellows and most of the - I mean probably about a third of our competitive research grants come from NHMRC. So it's been hugely important over the years, as you can imagine, to do that. We've got two programs at the moment - one in asthma and allergy and one in child development, in child epidemiology. We're thinking of another program grant in infection or in Aboriginal health. We've got fabulous NHMRC support for our capacity building grant. I've got 10 Aboriginal researchers fully funded by NHMRC for five years as part of the capacity building grant, which has just been spectacularly successful. You should see the difference between these Aboriginal researchers - most of whom are doing their PhDs, but we have some post docs as well - you should see how they've come on with the intense mentoring we've given them here. So that's been such a success story and I hope NHMRC continues to give these capacity building grants, particularly in Indigenous research. We were part of the Aboriginal road map, setting the road map for Aboriginal research, and I think certainly that commitment from NHMRC to fund 5 per cent of its budget for Aboriginal health research has been very beneficial for us. Yes, I think that NHMRC, for all its foibles - and sometimes you get very angry if they don't judge your research the way you thought it should be judged - has been a superb supporter of this institute, as have, I might say, the other institutes around Australia, who looked upon us as their little sister. I will be forever grateful to all of the eastern states institutes who let us share with them, with all their experiences and support - it's been absolutely gorgeous. People like Gus Nossal and Tony Basten and John Shine and John Funder have been extraordinarily helpful. This little research institute in the west, which is now nearly 500 people, so we're no longer little, but they were very helpful. Interviewer: I would say it looks like the taxpayers got a great return on their investment through the NHMRC and through your endeavours? Prof. Stanley: That's a very good way to put it. I don't think that research is costly. I think research is a great investment. What we've tried to do - which is unusual compared to the other institutes - we don't want to just publish, we want to translate. What's good about being in Western Australia is we have an intergovernment - I've just had two hours this morning actually giving evidence to a coroner's inquiry about suicide and other alcohol-related deaths in Fitzroy Crossing. You know, it's fantastic. You can just really try and influence policy, clinical practice, population health, very much more intimately in a small place. Interviewer: You'll be interested to know that one of the other people interviewed for the series was Wendy Hoy. I certainly got an interesting impression about the real difficulties that one has, though, working in these populations, particularly with managing chronic disease and so forth. Prof. Stanley: I think that Wendy's research has been terrific, and we've used that extensively in our lobbying both to the federal and the state governments about implementing what we know 9 now in terms of chronic disease, and Wendy's shown that beautifully in her data. It is a huge issue to work in the Aboriginal health area, but I think it is one of our most important areas to address. And I've really enjoyed, I must say, working with Aboriginal people, and they have changed the way I view my approach to various aspects of both research and health and my personal life. It's been a very interesting road. But it's really very important that we don't give up and I think research is a very exciting and important - has an exciting and important contribution to make to improve Aboriginal health, particularly focusing on prevention. Interviewer: A final question - if you had to give advice, which I'm sure you do regularly to a young either high school student or researcher, an undergraduate student, and they're sort of toying with the idea of whether they should go into medical research or into scientific research, what would your key piece of advice be to try to ensure they do follow that path? Prof. Stanley: I think that basically they probably can see how much fun I have and what an incredibly exciting career health and medical research can be. I think one of the things that's really very satisfying about it is to a certain extent you control your own agenda, and therefore you have the power to influence what you want to do better than almost any other career I can think of - you're the ones who are initiating the research, you're the ones who are writing the grants. Okay, it might be tough. You're never going to be a millionaire unless you go along the commercialisation route and hit it big time. But you're going to have this immense satisfaction of working with groups of people who are similarly committed, exciting people. You think of some of the characters in health and medical research. I mean, they're absolutely gorgeous, and lots of fun. And I get a sense that these people love working in this institute. There's a sense of great camaraderie. You should see this horrendous Christmas concert we have - it's absolutely appalling. But you'd only do that if you all really liked each other. No-one is immune from having the mickey taken out of them, even the director - in fact, particularly the director - and we have a lot of fun together. I think that people can actually see it has the potential to make a lot of difference to many of the problems in society which are actually not getting better. I think that there's almost, you know, five major big issues in the area of children and young people, which research is just important that we do - in mental health and in pathways into chronic disease and exposures in pregnancy and how they might, all the epigenetic stuff we were talking about. There are so many exciting problems for people to get stuck into. And what's more exciting now than it was in my day when I was making these decisions is the technology and the capacity that we have now to look at brain function, to look at what's happening in various systems in the body - structural biology, in the gene. It is just so much more - if I was going to start again, I'd do something like neuroembryology - I mean, some of the stuff we're going to be able to unpack is going to be so exciting in the future. I would just say to you if you want the most exciting career ever you could choose, this is for you. Interviewer: Fiona, that's a terrific advertisement. Again, thank you very much for your musings - they've been mighty. And I wish you all the best. Prof. Stanley: Thank you. Voice-over: This podcast was brought to you by the NHMRC, working to build a healthy Australia. To find out more, go to our website at www.nhmrc.gov.au. 10