Tsunami triggers coastal communities to `prepare` for disaster

advertisement

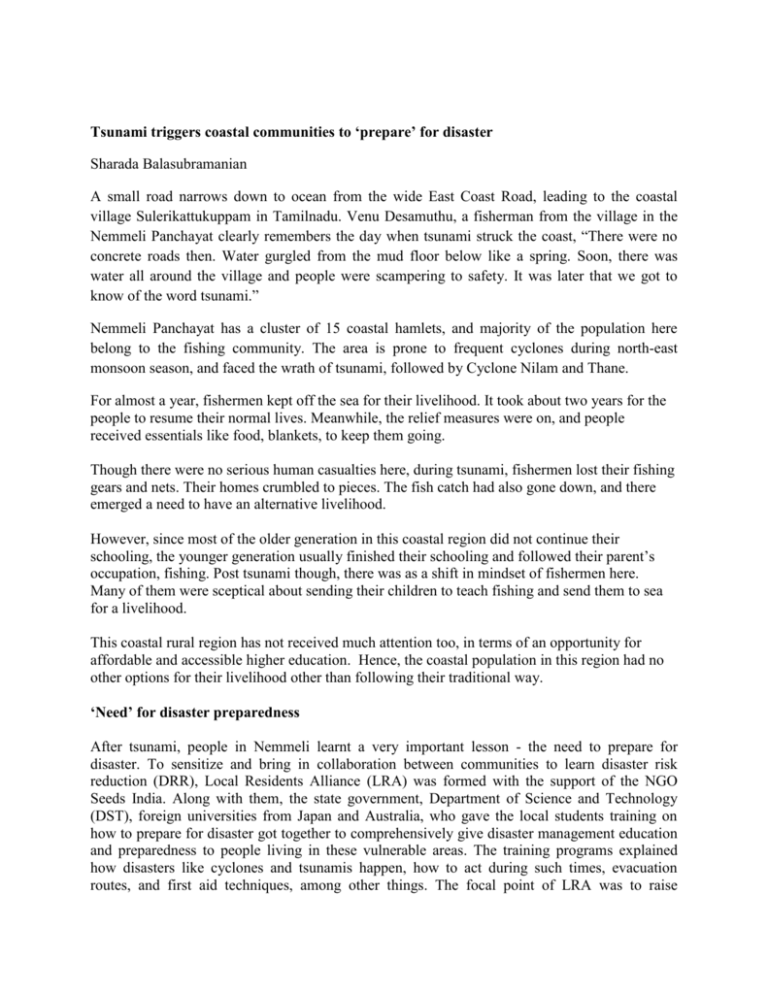

Tsunami triggers coastal communities to ‘prepare’ for disaster Sharada Balasubramanian A small road narrows down to ocean from the wide East Coast Road, leading to the coastal village Sulerikattukuppam in Tamilnadu. Venu Desamuthu, a fisherman from the village in the Nemmeli Panchayat clearly remembers the day when tsunami struck the coast, “There were no concrete roads then. Water gurgled from the mud floor below like a spring. Soon, there was water all around the village and people were scampering to safety. It was later that we got to know of the word tsunami.” Nemmeli Panchayat has a cluster of 15 coastal hamlets, and majority of the population here belong to the fishing community. The area is prone to frequent cyclones during north-east monsoon season, and faced the wrath of tsunami, followed by Cyclone Nilam and Thane. For almost a year, fishermen kept off the sea for their livelihood. It took about two years for the people to resume their normal lives. Meanwhile, the relief measures were on, and people received essentials like food, blankets, to keep them going. Though there were no serious human casualties here, during tsunami, fishermen lost their fishing gears and nets. Their homes crumbled to pieces. The fish catch had also gone down, and there emerged a need to have an alternative livelihood. However, since most of the older generation in this coastal region did not continue their schooling, the younger generation usually finished their schooling and followed their parent’s occupation, fishing. Post tsunami though, there was as a shift in mindset of fishermen here. Many of them were sceptical about sending their children to teach fishing and send them to sea for a livelihood. This coastal rural region has not received much attention too, in terms of an opportunity for affordable and accessible higher education. Hence, the coastal population in this region had no other options for their livelihood other than following their traditional way. ‘Need’ for disaster preparedness After tsunami, people in Nemmeli learnt a very important lesson - the need to prepare for disaster. To sensitize and bring in collaboration between communities to learn disaster risk reduction (DRR), Local Residents Alliance (LRA) was formed with the support of the NGO Seeds India. Along with them, the state government, Department of Science and Technology (DST), foreign universities from Japan and Australia, who gave the local students training on how to prepare for disaster got together to comprehensively give disaster management education and preparedness to people living in these vulnerable areas. The training programs explained how disasters like cyclones and tsunamis happen, how to act during such times, evacuation routes, and first aid techniques, among other things. The focal point of LRA was to raise awareness on local disaster and climate change induced risks at local level, bring in risk reduction and disaster resilience in local development programs. The group supports the local area in preparing development strategies that link disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation. This is keeping in line with their economic growth and poverty reduction objectives. The activities are planned in a collaborative manner. Fishermen said that this training programme will enable them to take action when disaster strikes. For instance, who to evacuate first, how to find the easiest route to escape were things the local community, etc. ‘Cyclone Shelter’ converted to Community College When tsunami struck, people took refuge in a cyclone shelter, a few kilometres from their homes. Today, a community college stands here, where fishermen’s children are pursuing their degree. Desamuthu’s son is doing his final year of commerce degree here. In 2011, with the support of the state government, the community college in Nemmeli was built to give fishermen’s children an opportunity to graduate and find an alternative livelihood. The courses that are offered here include Literature, Commerce and Computer Applications. The college not just gives regular lessons on their subject, but goes a step ahead to offer disaster risk reduction (DRR) as an elective course. The three main objectives of this disaster elective course were to develop an understanding on disaster management process, to understand the mitigation programs and understand the disaster management policies and legislations. The theoretical aspects were taught in the class. Group discussions, tour to neighboring villages to prepare hazard maps and collect household survey data happened through interactions with the local community. There are several advantages in introducing this course (1) students have faced fury of 2004 tsunami (2) their practical experience with tsunami and coastal floods in monsoon timing helped to understand the importance of this course and (3) It was easy to visit field sites to gain more practical knowledge. Whatever they learned in the class room can be linked to the field visit experience on the same day. It was observed that majority of the students in these villages have a sense of feeling that their class room knowledge should be used by their community so that their villages are geared up to act when disaster happens. After 7 years of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, the establishment of this college gave a new scope to bring this rural population in to main stream of higher education. Mapping Hazard The students from the college got together with the city students and the National Social Service (NSS) team to prepare hazard map for the villages. The result of this interesting and enriching experience lies right at the entrance of the village where hazard maps were put up. This colourcoded map showed the population ratio, the number of older people, women, and children living there and the evacuation route. Below this map, a blank space is left. Says Ignatius Prabhakaran, an anthropologist from Seeds India who is working closely with the communities, “People need to constantly remind themselves to prepare for disaster, so this empty space will be filled with sayings or quotes. This will be written by the local people in the local language. People will write them once in a fortnight just so that they remember disaster could strike any moment and preparedness is the key to survive.” Rajalakshmi Mahadevan, 22, a fisherman’s daughter, who is in her final year of college, headed the hazard mapping exercise, and today, she is confident, ready to take up a job and pursue her master’s degree. This would not have happened if the college wasn’t set up. “Education has changed my life”, she says. During the hazard mapping exercise, Rajalakshmi, along with other team members surveyed their villages. She says, “Since we were familiar with the local people, the comfort level was there and interaction was easy.” The local people got together with students in mapping their village. For instance, older people gave information about location of wells, ponds in the village, which was unknown to the students. This helped in understanding the village better. From every house, they collected information on the people who lived there, if they needed facilities like hospital, and so on. This information not just helped in understanding what their villages needed, but helped in discovering community issues. Awareness on health and hygiene issues were conducted too. The teams were divided and each worked on questions pertaining to socio-economics, environment etc. The task of setting up this college was Herculean indeed. Ramaswamy Krishnamurthy, a professor from Applied Geology department, Madras University, who was the backbone of this initiative, served as a principal here for four years. He shares, “I found it challenging to pull the young kids out of their cocooned homes and goad them to enter college. Many families were reluctant. I hired an auto, put a speaker on it, and went around the villages, asking people to bring their children to the college for their studies.” Once enrolled, the core was to build confidence among the minds of people. They had to train the students in life saving skills. Technology-based teaching methods slowly came in and interactive sessions using information communication and technology (ICT) helped them to learn better. The enrolled students received government scholarship worth Rs 5000, a free bus pass to commute from home to college. As four years passed, there was a sharp increase in the number of girls enrolling for the course. It was clearly a sign of progress. The students could go to college, not just because it was closer to their homes, but also because the cost of getting the degree was something that the fishermen community could afford. Where a normal college degree would cost Rs 25000 a year, a degree at the community college would only cost Rs 2500 a year. Impact of the College From a mere 67 students in 2011, the number of students studying here has seen a sharp rise to about 400 students. The students are first generation learners from a family background of Below Poverty Line (BPL). Though students from Nemmeli Panchayat are given preference for admission, villagers from neighboring villages are also joining this college. Many students who graduated from the villages are now working for multinational companies and are economically well-off. The local communities express that apart from enhancing the literacy level in the villages, growth of this college will have a significant impact at a societal level, as the value for land is increasing and there are new constructions and companies mushrooming up. This would lead to better employment opportunities for the college graduates, enhancing the lives of the fishermen communities. The students say that even if they get a job in a company they would never want to leave the coastal village, for this is home. Says Raghu Raja, a fisherman, “My daughter is now two years old. By the time my daughter grows up, there will be a huge demand for admission into this college.” Nemmeli Panchayat is an example where it has been established that higher education in rural areas did help the vulnerable communities to be disaster resilient. Now, efforts are underway to prepare community-based disaster management (CBDM) plan for Nemmeli Panchayat so that it can prove to be a model Panchayat in the state. The state government has given a 10 acre land adjacent to the college to establish permanent infrastructure and give better facilities for the students. Proposals are under consideration to introduce more inter-disciplinary and integrated 5 year courses, which will lead to a complete transformation of this coastal region by 2020.