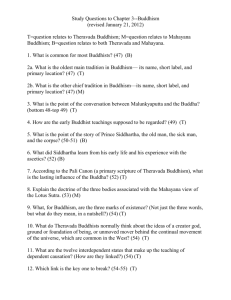

RMPS: Morality In The Modern World - Buddhism For

advertisement