coming to america - Widener University

advertisement

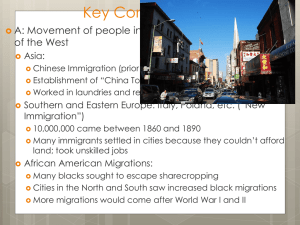

coming to america Ivan Light. Contexts. Berkeley: Spring 2004. Vol. 3, Iss. 2; pg. 65 Full Text (1334 words) Copyright University of California Press Spring 2004 coming to america Remaking the American Mainstream: Assimilation and Contemporary Immigration by Richard Alba and Victor Nee. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003, 359 pages. Twenty-five years ago, researchers optimistically assumed that today's Asian, Middle Eastern, and Latino immigrants would repeat the assimilation experience of the Southern and Eastern Europeans who had preceded them by a century. Their optimism rested upon the historic ability of American society to acculturate and assimilate immigrants, and the expectation that it retained the capacity to do so. Acculturation is defined as immigrants and their descendants becoming native speakers of English, and, more generally, adopting American folkways, values, lifestyles and ideology. Assimilation connotes the formation of personal relationships with people outside their group, especially through intermarriage, but also by moving out of immigrant neighborhoods and occupations into mainstream ones. Acculturation is easier than assimilation, and precedes it. Southern and Eastern European immigrants and their descendants required about a century to acculturate and assimilate; scholars expected that the most recent immigrants would do so within a comparable period of time. After a quarter-century of study, researchers are less optimistic about the capacity of American society to acculturate and assimilate the newer immigrants so quickly and effectively. First, the mass migration of Europeans ended between 1917 and 1924 because of restrictive and racist immigration laws. Afterwards, the American-born children and grandchildren of these immigrants came to adulthood without further inflow, which facilitated their assimilation. But there is no sign that the new immigration will end soon, if at all, depriving America of the same breathing space to integrate immigrants already here. Second, just half of the current immigrants are white. Arguably, racism will render the acculturation and assimilation of the other half much more difficult and problematic than was the case for Europeans. Third, European immigrants entered an industrial economy that offered plentiful jobs for unskilled workers. Above these bottom-rung jobs stretched a ladder of economic opportunity that their children and grandchildren could steadily climb. Today's immigrants enter an economy in the throes of global restructuring, in which low-level manufacturing jobs are exported to cheap-labor countries and lower-level supervisory jobs are disappearing. Opportunities for social mobility from the bottom of the economic order are scarcer than they were for earlier European immigrants. Fourth, European immigrants cut ties to their homelands when they immigrated. Thanks to new communication and transportation technologies, contemporary immigrants can retain their cultural ties to home (see Salsa and Ketchup: Transnational Migrants Straddle Two Worlds," Contexts, this issue). This renders acculturation and assimilation more difficult now than a century ago. Finally, in the past immigrants had to renounce their previous citizenship in order to acquire American citizenship; nowadays, countries that send immigrants to the United States tolerate and even encourage dual citizenship among their nationals abroad. Researchers also note that Americans have lost some confidence in the value of assimilation. Although Theodore Roosevelt denounced "hyphenated Americans," American political and cultural leaders now preach and promote multiculturalism and ethnic pluralism. Policies today legitimize and even strengthen the retention of ethnic identities, native languages and ethnic communities. Elementary schools teach young immigrants in their parents' foreign language rather than in English, states write ballots and driver-education pamphlets in foreign languages, university deans invoke diversity as a sacred value, and university ethnic studies centers inculcate identity politics. Talk-show pundits blame liberal academics for all these changes, but it is worth recalling that amicus curiae briefs in favor of affirmative action were filed not only by the American Sociological Association and the American Civil Liberties Union, but also by Fortune 500 corporations and the Pentagon. In this anti-assimilatory climate of opinion, Richard Alba and Victor Nee show courage in explaining why assimilation is happening anyway. The authors use cautious language to avoid being misunderstood. In general, they concede that the prospects for assimilation and acculturation are dimmer than they were a century ago. Nonetheless, Alba and Nee insist that assimilation still has "a major role to play in the future." The concept of assimilation has "not lost its utility for illuminating many of the experiences of contemporary immigrants and the new second generation" (p. 9). Evidence for this claim appears in Chapter 6, where the authors review the extensive scholarly literature on language change, economic mobility, residential segregation and intermarriage. In all these areas, they find that assimilation and acculturation are underway just as they were a century ago-if not necessarily quite so successfully. Switching to English is the crucial test of acculturation. Immigrants of all national origins still switch to English as the generations succeed one another, just as European immigrants did in the past. However, the generational movement to English is slower than it used to be. The rule used to be that by the third generation, all descendants of immigrants spoke only English. Alba and Nee report that 90 percent of third-gen-eration youth of Chinese, Filipino, and Korean extraction speak only English at home (p. 225). However, just two-thirds of third-generation Mexican and Cuban youth speak only English at home. "It does seem clear that loyalty to Spanish erodes over the generations," Alba and Nee tentatively conclude, but it is also clear that the switch to English was somewhat quicker among the European immigrants of yesteryear than it is among Hispanics today. Marrying outside one's ethnic group is the crucial test of assimilation. Among turn-of-the-century European-Americans immigrants, exogamy increased with each new generation. First, the European immigrants married people from the same country and of the same religion; their descendants married people of the same religion-for example, Irish Catholics married Polish Catholics. Later still, their descendants married across religious lines, and now they are increasingly marrying the children of new immigrants across racial lines. The odds that a college-educated Asian will marry a white person were 6 in 10 in 1990, up from 4 in 10 in 1980; the odds of a college-educated Hispanic person marrying a non-Hispanic white person were 2 in 10 in 1990, up from 1 in 10 a decade earlier. Alba and Nee conclude that assimilation is slower, but not stopped. So, they assure readers, the United States will not become a multicultural country. Just one-third of European Americans can trace their ancestry to white Protestants from the British Isles, who were the overwhelming majority at the time of the American Revolution. It is only because the other two-thirds assimilated into white Protestant society that one can say an ethnic majority exists in the United States now. In the same sense, today's assimilation will blur and in some cases dissolve the ethnic boundaries that now divide the American population. Alba and Nee acknowledge that some descendants of working-class immigrants will be trapped in oppositional ghettos for the foreseeable future, but this will not afflict most descendants of today's immigrants as pessimists have claimed. Remaking the American Mainstream corrects a scholarly generation's neglect of old-fashioned acculturation and assimilation, making a case for more continuity with the past than had been acknowledged. It does not explain how scholars should balance assimilation and acculturation with the pluralist models which anticipate looser coexistence of distinct ethnic groups into the future. But it does suggest thinking about this tension rather than assuming that assimilation is finished. For public policy, Remaking the American Mainstream also suggests that it is unwise to bet on the long-term survival of cohesive immigrant groups. This news will be unwelcome in ethnic studies centers on the Left. To the Right, it suggests the need to carefully balance arguments and facts rather than continuing to rely upon facile slogans about ethnic balkanization. [Author Affiliation] Ivan Light is Professor of Sociology at the University of California, Los Angeles. He is the author of seven books, including most recently, Ethnic Economies (with Steven Gold, 2000), Immigrant Entrepreneurs and Immigrant Absorption in the United States and Israel (with Richard E. Isralowitz, 1997), and Race, Ethnicity, and Entrepreneurship in Urban America (with Carolyn Rosenstein, 1995). In 2000, he received the Distinguished Career Award of the International Migration Section of the American Sociological Association.