Outscaling Agricultural Production and Market Linkages

advertisement

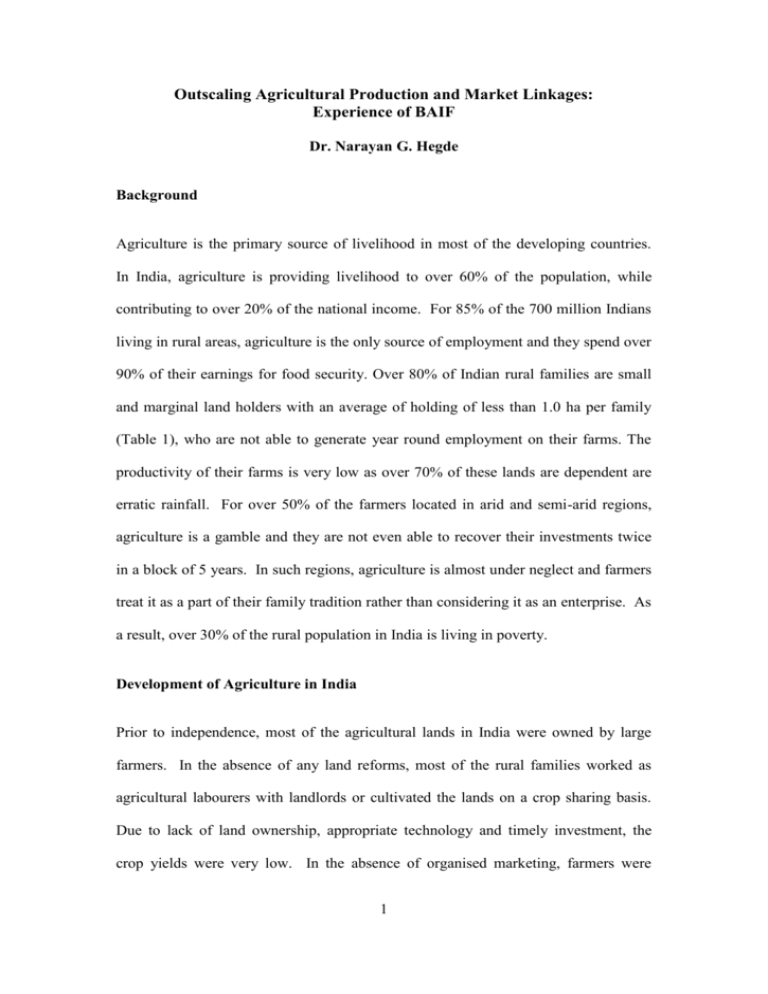

Outscaling Agricultural Production and Market Linkages: Experience of BAIF Dr. Narayan G. Hegde Background Agriculture is the primary source of livelihood in most of the developing countries. In India, agriculture is providing livelihood to over 60% of the population, while contributing to over 20% of the national income. For 85% of the 700 million Indians living in rural areas, agriculture is the only source of employment and they spend over 90% of their earnings for food security. Over 80% of Indian rural families are small and marginal land holders with an average of holding of less than 1.0 ha per family (Table 1), who are not able to generate year round employment on their farms. The productivity of their farms is very low as over 70% of these lands are dependent are erratic rainfall. For over 50% of the farmers located in arid and semi-arid regions, agriculture is a gamble and they are not even able to recover their investments twice in a block of 5 years. In such regions, agriculture is almost under neglect and farmers treat it as a part of their family tradition rather than considering it as an enterprise. As a result, over 30% of the rural population in India is living in poverty. Development of Agriculture in India Prior to independence, most of the agricultural lands in India were owned by large farmers. In the absence of any land reforms, most of the rural families worked as agricultural labourers with landlords or cultivated the lands on a crop sharing basis. Due to lack of land ownership, appropriate technology and timely investment, the crop yields were very low. In the absence of organised marketing, farmers were 1 unable to get remunerative prices for the commodities. There was no agricultural extension service to motivate farmers to boost agricultural production. With increasing population growth without any significant effort to enhance agricultural production, there was a severe shortage of foodgrains during the 40’s and early 50’s, which compelled India to import foodgrains to feed the farming communities. Table 1: Agricultural Land Holdings in India (1995-1996) Landless Marginal holders Small Holders SubMedium Holders Medium Holders Large Holders Total Size of Holding (ha) No. of Holdings (m) % of Total Holdings Total Area held (m ha) % of Total Area NIL Below 1.0 20.00 50.50 18.83 46.16 28.12 17.20 Av. Area / Holding (ha) 0.57 1.0-2.0 16.10 14.72 30.722 18.8 1.91 2.0-4.0 12.50 11.43 38.953 23.80 3.12 4.0-10 8.10 7.40 41.393 25.40 5.11 Above 10 2.20 2.01 24.163 14.80 10.98 109.40 100.00 163.227 100.00 - The first step to boost agricultural production by the Government of India was to initiate agricultural reforms to empower the tillers to own the land. This was helpful for the rural families to take interest in agricultural development. To introduce new technologies in agriculture, the Government of India launched an ambitious community development programme in the early 50’s. Under this programme, field demonstrations were laid out to highlight the impact of improved seeds and fertilisers on the yield of various crops. Simultaneously, huge investments were made for establishing major irrigation schemes and to set up fertiliser factories. This was helpful in improving the agricultural production. However, the major boost to agricultural development came in the early 60’s through genetic improvement of staple food crops. With the release of high yielding varieties of paddy, wheat and 2 maize, backed up with introduction of irrigation and high level external inputs, there was a significant transformation in Indian Agriculture, popularly known as the ‘Green Revolution’. This could help in achieving self-sufficiency in food supply. Simultaneously, agricultural markets were reformed to ensure a fair price for farm produce and minimum support prices were fixed for major food crops. Further, the Government arranged for procurement of grains through the Food Corporation of India to sustain the demand and remunerative price for the produce. The benefits of Green Revolution which were initially harnessed in Punjab and Haryana were gradually extended to other parts of the country during the next two decades till the early 90’s through intensive research, development and extension programmes. The Government of India made adequate budgetary provisions and established linkages between International and National Research Organisations and the Agricultural Extension Networks for development of appropriate technologies and their dissemination at the grassroot level. The Green Revolution was thus considered as a major landmark in the history of Indian Agriculture. However, there was severe criticism that it created a wider disparity between the rich and the poor. It was true that the technologies promoted for improving agricultural production benefited only those farmers who had good quality land, assured source of irrigation, adequate financial resources, critical inputs and connectivity with the market. Naturally, rich and educated farmers took advantage of the opportunities while the small farmers could not get significant benefits, except for working as agricultural labour. Nevertheless, there was plenty of food and significant control on rising food prices, which brought economic stability to the country. Agriculture turned out to be a major contributor to the national economy with over 35-40% contribution to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). 3 By the early 90’s there was a stagnation in agricultural production. There was no significant increase in either the crop yields or in the cropping intensity (Table 2). The growth in agricultural production declined from 4.7% during the Eighth Five Year Plan period (1992-1997) to 2.1% during the Ninth Plan Period (1997-2002). The growth has further declined to 1.5% during the period of the Tenth Plan (20022007). While there was no major increase in the price of foodgrains, the input costs had increased significantly to reduce the profitability of food crop production. In the absence of subsidies for phosphatic fertilisers, potash and micro-nutrients, farmers did not apply the required doses of fertilisers to maintain a desired balance between NPK fertilisers. Such unbalanced fertiliser applications could not boost the crop yield. Higher doses of fertilisers had an adverse affect on the soil micro-flora and productivity. On the contrary, many of the high yielding varieties were susceptible to pests and diseases. Intensive monoculture had placed the farmers in a high risk bracket, without any outlet to escape from failures. Table 2: Performance of Important Crops in India Crops Rice Wheat Total Cereals Total Pulses Total foodgrains Sugarcane Condiments and Spices Fruits and Vegetables Oilseeds Cotton (Bales) Gross Cropped Area % Percentage of Gross Cropped Area 1992-93 2002-03 23.27 23.47 13.70 14.35 53.36 12.45 12.13 63.44 65.49 1.99 2.69 1.20 1.72 Average Yield t / ha 1992-93 2002-03 1.74 1.74 2.33 2.65 1.46 1.53 0.57 0.53 1.46 1.53 63.84 63.58 1.08 1.34 8.45 4.78 10.98 12.87 14.92 4.20 100 (179.48 m ha) 13.59 4.36 100 (174.19 m ha) 1.17 1.51 1.19 1.12 4 Per capita availability gm / day 1992-93 2002-03 217.00 228.7 158.6 166.6 434.5 458.7 34.3 35.4 468.8 494.1 Due to lack of price support and organised markets, it was risky to diversify from food crops to cash crops. Lack of private investments in post production activities and inefficiency of food processing industries in the public sector failed to add value to the produce. In the mid 90’s, the investment in agriculture came down from 4.5% to 1.5% of the GDP. As a result, farmers particularly the small holders, are under severe economic pressure which needs to be addressed on priority. Present Status of Farmers and Scope for Outscaling Production While analysing the present status of Indian farmers and exploring the scope for outscaling agricultural production, it is necessary to address them in two categories namely, those who have good quality land and assured water resources to produce yields well above the average and the other category for those who are dependent on rainfall with yield well below the average. With regard to the first category, who have been taking advantage of modern technologies and inputs, there is scope for further improvement in the yields through the following inputs: 1. Application of balanced doses of fertilisers, based on the soil analysis and improvement in methods of application; 2. Enhanced use of organic manure and biofertilisers to improve the soil health and productivity; 3. Efficient water use and conservation; 4. Change in the cropping pattern and crop rotation: introduction of high value crops; 5 5. Efficient extension services to provide timely advice to farmers; 6. Mechanisation and introduction of efficient tools and equipment for improving the efficiency and saving labour; 7. Post production support such as efficient harvesting, threshing, storage, processing and marketing; 8. Crop insurance and easy access to credit. A majority of the small farmers who fall in the second category and whose lands located in arid and semi-arid regions are heavily sub-divided and fragmented and deprived of irrigation facilities, are struggling to earn their livelihood. The available technologies for enhancing crop production are not suitable for such lands. These farmers being poor, are not capable of mobilising necessary resources for optimising the production. As these farmers are left with very little surplus produce, there is no serious effort to link their production in the market. As a result, they suffer due to price fluctuations, rigging of commodity prices by unscrupulous traders, wider variation in the quality and high cost of marketing. The other problem of small farmers is lack of information and awareness about modern and appropriate technologies. Realising these problems, various efforts are being made by the Government and Non-Government Organisations to boost the production of small farmers and link them with the market. Outscaling Agricultural Production by Small Farmers As development of small farmers has a direct impact on the national economy and alleviation of rural poverty, various programmes have been launched by the 6 Government of India. Significant among them are watershed development and promotion of dryland agriculture, priority for minor irrigation and lift irrigation schemes, special assistance for drip irrigation and greenhouse farming, promotion of contract farming and corporate farming and agricultural finance through Self Help Group and micro finance institutions. With regard to post production facilities, the Government of India has provided incentives for the private sector investment to build storage facilities for the benefit of small farmers. Agricultural market reforms have been introduced by changing the existing Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee (APMC) Act for setting up competitive rural markets and to facilitate direct sale of farm produce, without entering the market yard. Dryland development programme has a greater impact on agricultural production, as over 60% of the gross cropped areas spread over 123 districts are covered under drylands. Drylands contribute to 45% of the total food production in the country. However, as these areas are prone to drought, the chances of crop failures are high. In the absence of adequate moisture, agricultural operations are restricted to 80-100 days, resulting in heavy underemployment and distress migration. Due to low productivity, such lands are often under neglect, resulting in heavy soil erosion and runoff of rain water. Considering these problems, the Government of India has launched a major programme of watershed development in arid and semi-arid regions of the country. Timely availability of credit being the most critical input, small farmers often fall into the debt trap of moneylenders. To provide adequate finance at a reasonable rate of interest to meet the consumptive and productive needs of finance, the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) and other private sector banks 7 are coming forward with liberal terms which can be routed through SHGs without collateral security. Such a drive is expected to empower the rural women to a great extent. The Government of India has also been encouraging Public-Private Partnership for consolidation of fragmented production and introduction of best practices for processing and marketing of agricultural produce by enhancing the investment from the current level of 1.5% to 5-6% of the GDP. Efforts are also being made to share market and technical information with farmers through village level information centres and all the available mass media. However, most of the Government programmes suffer due to poor delivery and implementation, where small farmers remain the worst affected. Role of CSOs in Outscaling Production and Market Linkages There are many civil society organisations (CSOs) which are engaged in helping small farmers to make best use of the available opportunities to boost agricultural production. With their bottom-to-top approach and flexibility, many such agencies have made a significant contribution to the rural economy. Most of these CSOs have the primary objective of conserving the natural resources and improving agricultural production through sustainable use of the available resources. Thus the focus is on the small landholders. There are a few organisations engaged in promoting sustainable agriculture, particularly organic farming. BAIF Development Research Foundation (BAIF) is a CSO which recognises the importance of production by masses rather than mass production for ensuring food security and social justice. BAIF is promoting multi-disciplinary development 8 programmes to generate gainful employment through promotion of livestock development, water resources management, sustainable agriculture, particularly through establishment of agri-horti-forestry on hilly terrains to rehabilitate the tribals. All these programmes ensure environmental protection, women empowerment and development of strong people’s organisations at the grassroot level. Such a multidisciplinary development ensures income from various sources to meet their needs, while preventing the risk of failure. As the land resources owned by small farmers are very small, it will be difficult for them to earn their livelihood from crop production alone. Thus livestock husbandry and various non-farm enterprises are being promoted simultaneously. BAIF’s Approach to Sustainable Agriculture With this background, BAIF has been providing support services to the rural poor to earn their livelihood, making optimum use of the degrading natural resources such as marginal and wastelands. For effective communication with the farming families, the strategy is to form SHGs or Users’ Groups of various services, belonging to homogenous socio-economic status and encouraging them to identify their problems and needs. They are being introduced to various options which can address their problems and are encouraged to plan various activities to suit individual members. These groups identify their inputs and financial needs to carry out the production and the SHGs with the guidance of the facilitation team procure these resources. Such initiatives not only build the capabilities of the SHGs, but also ensure good quality inputs at a reasonable cost. The groups meet regularly depending on the needs. During these meetings, the members raise their doubts and problems and the extension workers and resource persons of the project guide them suitably. This is a 9 better approach for transfer of new technologies as the State Agricultural Extension Officers have not been able to communicate effectively with individual farmers, particularly those who are illiterate and living in remote areas. To avoid this problem, BAIF has been engaging local unemployed youth to work as field guides. In the absence of large holdings, the best option is to outscale the production through small farmers by organising common services such as procurement of inputs, finance from micro-finance institutions or banks, technical guidance, equipment-hire services and post-harvest activities such as collection, storage, processing and marketing. Some of the successful programmes launched by BAIF to outscale agricultural production by small farmers are presented below: Involvement of Small Farmers in Milk Production Milk production in Western countries is being organised through large dairy farmers, whereas in India, it is the small farmers who own 2-4 cattle and buffaloes more to meet the domestic needs, than to operate it as an economic activity. However, under the ‘Operation Flood’ programme, dairy cooperatives were promoted at the village level to collect milk from small producers and supply it to large dairies established in the cities. The activities were however restricted to only certain milk pockets which were the native tracts of good cattle and buffalo breeds. In the absence of critical support services, it was difficult to expand dairy husbandry to other areas, although there was good scope throughout the country. Although the State Animal Husbandry Department had set up the breeding centres at the block levels, small farmers living in interior areas were neither aware of the benefits of dairy husbandry nor were the services provided, of superior quality. 10 Realising the potential of dairy husbandry to provide livelihood to small farmers, BAIF decided to provide door to door service which covered motivation, training in various skills, delivery of breeding and health care services, regular technical advice and formation of dairy farmers’ groups to closely interact among the farmers. Such users’ groups organised milk collection at the village level through their cooperatives and supplied it to dairy plants. The paravet, who facilitated the above services was be available to the farmers as and when needed. In most cases, the paravet played the role of a community leader by motivating the dairy farmers to adapt best practices to improve the milk production and profitability. With such a handholding approach, many small farmers gained confidence and took greater interest in rearing good quality cows and buffaloes. BAIF was able to demonstrate the feasibility of providing sustainable livelihood with 2-3 high yielding cows or buffaloes. Today most of these small farmers pay for all these services. Promotion of Tree based Farming for Rehabilitation of Tribals Over 9% of the Indian population is represented by tribals, who have been traditionally living in the forests, dependent on collection of forest products for their livelihood. With the degeneration of forest resources over last 5-6 decades, these families have been compelled to take up agricultural production on degraded lands on the periphery of the forests which further threatened the eco-system. Considering the serious problem of degeneration of forest resources and drudgery of the forest dwelling tribal population, BAIF initiated a horti-agri-forestry programme to rehabilitate the poor tribal families in Valsad and Navasari districts of Gujarat State. These villages are located in the foothills of the Western Ghats, running along the Arabian Sea, at an altitude of 250 to 300 m. The average rainfall is 2000 to 2500 11 mm distributed between June to October. Being shallow, gravelly, the soils did not facilitate easy percolation of rain water. As a result of heavy soil erosion and runoff of rain water, the tribals faced severe scarcity of water during March-May. They grew crops like finger millet, pearl millet or sorghum during rainy season, which provided employment for 60-80 days during the year and yielded 600-800 kg grains/ha. Unable to make their living with such meagre income, they were forced to migrate after the harvest. Women were also forced to work hard, inspite of their poor health conditions, while the children were neglected and deprived of health care and education. These families were earning Rs. 6000-8000 per annum (USD 1= Rs. 44.50), from agriculture and wage earnings. The project aimed at rehabilitating these families on their degraded lands through horti-agri-forestry. BAIF with its experience in promotion of wastelands development through afforestation, convinced the tribals to adapt tree based farming. However, during their interaction with the project staff, the local communities expressed their lack of interest in cultivating forestry species, as they already had easy access to forests to meet their bio-mass requirements and the expected income from forestry plantations was not adequate to sustain their livelihood. They were prepared to establish fruit plants which could provide regular income. Hence, BAIF modified the action plan and designed a horti-agri-forestry model on 0.4 ha degraded lands for each family, with fruit species as the main crop with various multi-purpose tree species on field bunds and borders and local food crops in the interspace. As over 75% of these families had their own lands, the programme enrolled most of the families. With good water and soil conservation measures, contour bunding and intensive tillage, the yield of intercrops increased by 40–100%. This could address the problem 12 of food security during the first year itself and sustain the interest of the farmers to nurture the orchards. During the process of orchard development, many technical and social problems were encountered in the field. These problems could be addressed from time to time through innovative approaches, which in turn contributed to the success of the programme. Over the last 20 years, this programme has proved to be a successful model for rehabilitation of tribals throughout the country. During this process, it was observed that profitability was a motivating factor for farmers to work hard to improve the production. Support in the form of input supply and technical guidance were critical. Linkage with the market was another important factor for enhancing the profits. Critical Inputs for Outscaling Production by Small Farmers Capacity Building: As the poor tribals who had never been engaged in horticulture development were diffident in implementing this project, motivation and creating awareness about the benefits of the programme were given priority in the initial period. As the women had a special role in orchard development, special programmes had to be developed to empower them. When women started working for establishing orchards, it was realised that many of them were anaemic and prone to frequent illness, mostly related to water borne diseases and malnutrition. Lack of family planning, shorter interval between childbirths, lack of pre-natal and post-natal care, nutritional deficiency and sickness of children also affected their health and reduced their work output. Furthermore, they had to spend significant part of their time everyday in collecting water, fuel and fodder, and were left with very little time to take up economic activities. Thus, it was necessary to address their drudgery, provide primary health care and safe drinking 13 water to empower them to take up orchard development. Installation of hand pumps, promotion of smokeless wood stoves, training of traditional midwifes and herbal healers and training of local youth to serve as health guides were some important activities which empowered the women. As motivation and communication with individual families, particularly with women were extremely difficult and time consuming, the women were encouraged to form SHGs of 10-15 members, to interact among themselves and with the project staff. For planning various development activities and to create common services, village level Planning Committees were established. These People’s Organisations could strengthen local infrastructure to provide critical services and to sustain the programme. The SHGs were further utilised to promote small savings and micro finance, planning of various activities by individual families and by small groups. The SHGs could ensure effective participation of local families, mobilise finance and sustain the progress of their community. As most of the participating families were illiterate and spread over remote hilly areas, there was a need for regular dialogue and handholding to carry out various activities related to orchard development. As these villages were backward and deprived of basic amenities, it was difficult for the Agricultural Extension Officers to stay there. Thus local youth, who had dropped out of secondary school were selected as field guides to assist the project officers. These youth were trained in different aspects such as orchard development, community health and sanitation, operation and repairs of hand pumps and bore wells, etc. for 1-2 months and assigned with the responsibility of assisting 30-50 families in the village. This arrangement gave a boost to the confidence of the tribal families as they could easily approach the field 14 guides for guidance. The project paid a small honorarium to field guides based on their output. With the progress of the project, these field guides have become very popular and turned out to be community leaders. They are serving as mentors for the families who have been trailing in the development process. Production and Supply of Inputs: As the programme needed large quantities of inputs which were not locally available, the participants were encouraged to take up the production of inputs like grafted plants of mango and cashew, seeds of various arable crops, vermicompost, bio-pesticides, etc. Other inputs like fertilisers and plant protection chemicals were procured for distribution. Equipment and tools like sprayers, threshers and mobile pump sets were also procured to provide them to the villagers on hire. These activities were coordinated by village level Planning Committees represented by nominees of local SHGs. Such backward integration encouraged other farmers as well to participate in the programme. Finance was another constraint to procure some of these inputs. This was arranged through their SHGs who borrowed from financial institutions. Post Production Support and Marketing: Linkage with market was another important factor influencing the profitability. The project area was known for mango cultivation and there was no difficulty in marketing the produce. However, the farmers were being exploited in many ways, particularly when the varieties grown were not superior in quality. So the project team in consultation with the participating families decided to introduce Alphonso, Kesar and Rajapuri varieties which have good demand in the local markets as well as in cities. However, the traders and local middlemen started exploiting the orchard owners by offering prices right at the stage of flowering. Many farmers lost heavily in such deals. So an idea of selling fresh 15 produce in leading markets was considered, instead of dealing with local traders. It was difficult to get a fair price even in market yards as traders formed their ring to suppress the price. So it was decided to set up a cooperative fruit processing unit to process part of the produce and to deal with elite urban customers directly for sale of fresh fruits. After setting up a processing unit for production of pulp, squash, jam, pickle, etc., various bulk consumers and marketing agencies were approached but it was difficult to find reliable agencies. Apna Bazaar, a leading co-operative consumer stores in Mumbai agreed to buy 5 tons of mango pickle, but they had their specific recipe. The co-operative accepted the conditions and signed a deal. This was helpful in standardisation of the products to suit the market needs. Food and drug license was obtained for processing food products. With the initial credibility, efforts were made to market the products in the nearby districts. The retailers gave good suggestions on the quality and packaging, which were modified to suit the market needs. To provide employment for landless and to introduce efficiency, decentralised semi-processing units were set up. After about 10 years, the Vrindavan Cooperative Food Processing Society, owned by the tribals, has recorded an annual turn over of Rs. 30.0 million (US $1 = Rs. 44.50). With stabilisation of major products, several new products have been developed with the help of local food technologists. BAIF has established exclusive shops in a few locations for direct marketing, particularly to get feedback from customers. With the stabilisation of marketing of processed products, the cooperatives were encouraged to sells fresh fruits during the season. As there was a wide variation in the fruits produced by a large number of small growers, grading of fruits was 16 introduced by training the members of the SHGs/Village Planning Committees in grading, packing and handling of fresh fruits. Thus, these products could fetch a premium price and received good publicity in the cities. Subsequently, selling was linked with elite consumers working in cities through their organisations. With regard to other products such as foodgrains, vegetables, agricultural inputs and handicrafts produced by the villagers, the village level planning committees decided to organise weekly markets in open areas on different days in different villages. This encouraged the participant families and their groups to take the products to the market for direct selling. In this process, these producers were able to establish direct contact with the consumers. They could gauge the demands and expectations of the consumers. This was very helpful to change their mindset and reorient their production to meet the demands of the consumers. This could also help to avoid several tiers of middlemen and reduce the cost of marketing. With these arrangements, the participant families were able to sell their produce at remunerative prices and earn Rs. 25,000-30,000 (USD 500-600) annually per family. Looking at the profitability, the families took keen interest in enhancing their production and farmers from neighbouring villages and districts started adapting this programme. Key to Success Thus capacity building, supply of critical inputs, technical guidance and suitable infrastructure for post production activities such as processing and marketing are critical to outscale agricultural production through small farmers. Summary India has reached self sufficiency in food production during the last four decades through Green Revolution. However subsequently, there has been a stagnation of 17 growth which has been a cause of serious concern. There are also a large number of small holders who have not been able to take advantage of the technologies and improved varieties which were responsible for increasing the production. Therefore there was a need to develop a new strategy to outscale production both in irrigated areas as well as in arid regions in the country. For improving the production, it is necessary to improve the fertility and replicate the technologies based on soil fertility analysis, improved use of biofertilisers, efficient water use and conservation, change in the cropping pattern and crop rotation through introduction of high value crops, efficient extension services to provide timely advice to farmers, mechanisation and introduction of efficient tools and equipment to improve the efficiency and post production support, easy access to credit and crop insurance and efficient extension services at the doorsteps of the farmers. With regard to the improvement in agriculture on degraded arid lands owned by small farmers, the strategy should be to organise the farming families into homogeneous groups to share information and technology and organise forward and backward integration. Innovative approaches are needed for handling the illiterate and weak farmers to ensure that they have no difficulty in adapting improved practices to boost the production. Collective marketing plays an important role. Inspite of all the efforts, as over 80% of the land holders own less than 2 ha with an average of 1 ha per family, it is extremely difficult for them to earn their livelihood from agriculture alone. Hence livestock should be an integral component of the agriculture extension programme to ensure sustainable livelihood in Rural India. 18