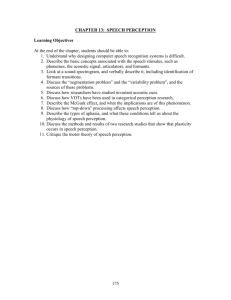

1. The Problem of Perception - SAS

advertisement