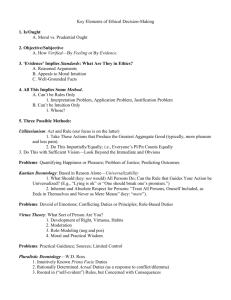

Prudential Arguments from Fundamental Interests

advertisement