The Generation-Skipping Transfer Tax

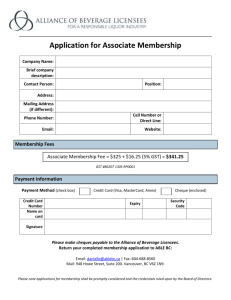

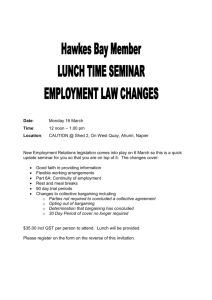

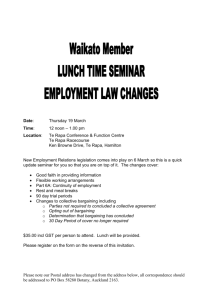

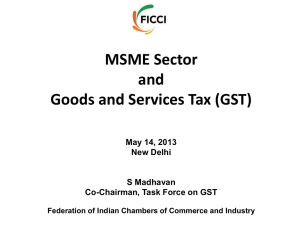

advertisement