Position statement - The Scottish Marine Wildlife Watching Code

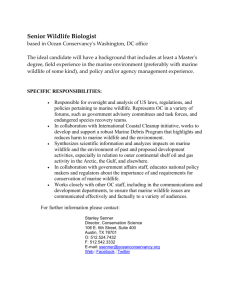

advertisement