12. William Marshal - some personal reflections

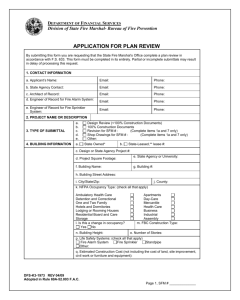

advertisement

WILLIAM MARSHAL --- some personal reflections We have now entered the Anniversary Year of the sealing of the first Magna Carta and the great day is only five months away! Predictably there has been a flurry of enthusiastic media comment about it being the “Cornerstone of Democracy”, with two new books being published. The BBC talks on Magna Carta by Melvyn Bragg were excellent, though it was a pity that William Marshal’s key role in the reissuing of the Charter in 1216 and 1217, when he was Regent of England, was not specified. Some of the media comments, however, have strayed into sensational speculation such as the claim that the Charter guarantees Scotland’s independence or that Magna Carta should be used to determine the rights for MI5 and MI6 to tap telephones! We must expect more of this as the popular press gets interested in the subject and, no doubt, there will be a backlash of critical comment as the hype goes over the top. I intend to use these last few articles before June to bring out some aspects relating to William Marshal senior and his family which I have only touched on so far and which have intrigued me personally. Generally I am amazed by what I still do not know about him. He played a major role in the strengthening of several castles in South Wales. The guide book for Goodrich Castle, near Ross on Wye, tells of him being among the greatest castle builders of the age and devotes two pages to him and his family. Wikipedia shows what he did for Pembroke and Chepstow Castles – I have not looked at the 11 other castles which at one time or another he controlled in England, Wales and Normandy, but it is obvious that his military knowhow would have been used to update them. Then there is his role in Ireland where he was, through courtesy of his wife’s inheritance, Lord of Leinster, a quarter of the island, at an awkward time when the Normans were still hated and his overlord, King John, was antagonistic to his position there. His land in Ireland contained no less than another 11 castles, though some may have been rudimentary. I was surprised to find from an Irish lady, whom I met on holiday, that she had spent a lot of her school time studying Guilliame de Mareschal. My attempts to follow this up on the internet did not bear fruit. Much of a booklet on The Temple Church in London and Magna Carta relates to William showing his importance to the Knight’s Templar. What did he do in Jerusalem in 1185-7? He was not the kind of person to sit around and do nothing. What was he doing founding an abbey in Cumbria far away from his other possessions and, more locally, how did his known friendship with Edward, Abbot of Notley Abbey, develop and affect his life? King John had given him the pastoral staff at Notley, an office that was passed onto his sons. We, or at least I, know little about his life in Normandy in 1190-9. Yet Longueville was said to be his favourite home where he and Isabel brought up their young family. It was said to be the plum manor that he got out of the Giffard estate. And what made Caversham, another Giffard manor, one of his favourite residences which he chose for his deathbed? Besides showing that I have got a lot to learn, these omissions show what a great man he had become. I hope to look further into his career in a later article. There are two particular aspects of the Marshals that have intrigued me. Firstly, that such an obviously fit man could father late in life five sons and five daughters, with the daughters producing 29 children from 7 marriages, but the sons collectively being childless from their 6 marriages. The failure of the male line had, of course, a profound effect on Long Crendon. Our history would have been very different if we had not been divided up. One recalls the curse of the Irish Bishop whom William had antagonised. Maybe there was a genetic reason, but the practice of marrying more for family aggrandisement than for love, with betrothal and marriage at very young ages, could not have helped the Marshal boys to have children. William junior’s first wife died young after only two years of marriage. His second wife, King John’s sister, was only nine years old at marriage and barely 16 when William died. Richard went the other way marrying a much older woman who had already been married twice, the first time 25 years previously. Less is known about the wives of the other three brothers, but Gilbert’s marriage to the youngest daughter of the King of Scotland, Walter’s marriage to a widow of the de Lacy family and Anselm’s to a member of the de Bohun family all suggest that they were made for political reasons. Secondly I was surprised to find that the title of Earl Marshal held by the current Duke of Norfolk directly stems from “our” Marshal family. The title is hereditary and passed from William’s grandfather, Gilbert the marshal of the royal household. As often happened in those days a person’s title or trade became their surname. The title had become an honorary one by the time William inherited it from his brother, but still conferred considerable status. When the male Marshal line died out in 1245, it immediately passed to the eldest son of William’s eldest daughter, Maud, who had married Hugh Bigod, Earl of Norfolk. It has remained with that family to this day. Seemingly the Marshal Earls of Pembroke were generally referred to as Earls Marshal and this title transferred to the Norfolk family.