The Role of a Clinical Pharmacist and Poly

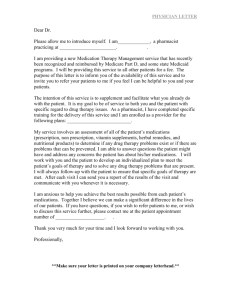

advertisement

THE ROLE OF A CLINICAL PHARMACIST AND POLY-PHARMACY IN THE PRIMARY CARE CLINIC Objective - To evaluate the outcomes and acceptance, by both patient and physician, of a clinical pharmacist (CP) as a member of the health care team in a primary care setting in Israel. Research design - Survey Setting - HMO primary care clinics in Israel Participants - 50 primary care physicians, recruited on a voluntary basis. Each was provided with a list of all of his patients that were taking at least five medications. From this list each physician selected 5-8 patients for CP consultation. Intervention - Each patient underwent a formal structured interview by the CP. The CP was allowed to make recommendations concerning the proper use of medications and lifestyle changes but not make changes to the patient's medications. A summary report of each interview and the CP's recommendations were sent to the referring physician and individually discussed. Final treatment decisions were the prerogative of the treating physician. Results- During 2004, 414 patient interviews were preformed. 33 patients were excluded due to death or severe chronic diseases. We report the results from 381 patients. 365 of the patients had at least one or more of the following chronic conditions: hypertension, diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease, asthma and CHF. 56% were over 65, 44% were male and 56 % were female. The number of monthly prescription medications per patient ranged from 4-18 with a median of 7. More than 50% of the patients took over the counter medications that the referring physician frequently was unaware of. It was also discovered that many patients took "nutritional supplements" that they did not consider medications. The following types of changes were recommended by the CP to the referring physician: Additional medication (50% of the patients), Discontinue medication (29%) Alternative medication (26%), Change in dosage (28%), Drug interactions (18 %). In addition the CP made between 1-5 direct recommendations to the patient concerning the proper use and storage of medications, the use of glucose and blood pressure home monitoring, the use of nebulizers and inhalers and lifestyle changes. We had major concerns about the willingness of physicians and patients to accept recommendations from a CP. We surveyed a random sample of 22 of the participating physicians to evaluate their response to the process. 100% of the physicians were satisfied with the process, 81% felt it added to their knowledge and 68 executed the CP recommendations. 55% also felt that it improved their patient's compliance. In a random survey of 55 patients, 78% felt that the interview with the CP improved his knowledge and 89% felt that as a result, they took their medications in a more orderly fashion. Conclusions - The results of this study, while recognizing the limitations of a survey, strongly suggest that there is a need for improved monitoring of medication use in the primary care setting and that a CP is an appropriate addition to the primary care team. The role of the primary care physician has changed, and he spends a much greater portion of his time treating patients with multiple chronic illnesses. These patients take multiple and complex medication regimens that are difficult both for the patient and the physician to comply with. This study supports the premise and the need to use additional support personnel such as a clinical pharmacist to improve compliance. The next step is to carry out a controlled trial to demonstrate that a CP can result in a meaningful change in patient outcomes.