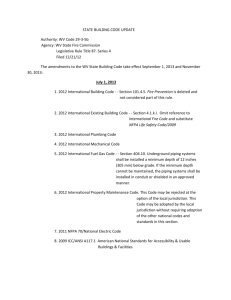

BACKGROUND - NYU School of Law

advertisement