Comprehesive3_Shen

advertisement

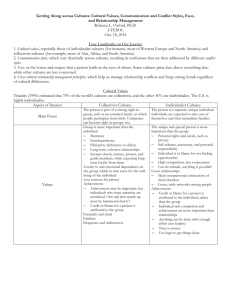

Comprehensive Exams/Dr. Fuyuan Shen Nan Yu/March 13, 2008 Questions: My question is about cultural differences and information processing. Please discuss the differences between individualistic and collectivistic cultures, and their implications for cognition and emotion. Review and summarize existing research in areas such as advertising, consumer psychology and communications that illustrates the impact of cultural differences on message processing. 1) Unpacking individualism and collectivism Individualist vs. collectivist cultures Over the past two decades, the cultural dimension of individualism and collectivism has been central to cross-cultural research and has attracted substantial attention from scholars from consumer psychology, cultural psychology, marketing and communications (for a review, see Triandis, 1995; Aaker, 2006; Shavitt, Lalwani, Zhang, & Torelli, 2006; Oyserman, Coon, & Kemmelmeier, 2002). Hofstede (1980) was one of first scholars that define individualism as “a focus of right above rights above duties, a concern for oneself and immediate family, and emphasis on personal autonomy and self-fulfillment, and the basing of one’s identity on one’s personal accomplishments (p. 4, as cited in Oyserman, Coon & Kemmelmeier, 2002).” On the other hand, rather than seeing collectivism as a simple opposite of individualism, researchers tend to focus on the consequences of the collectivism when defining it. For example, people from collectivist societies may share more common goals or values, or have a broader view of who could be in-groups than those in individualist societies. Moreover, collectivism implies views including 1) each individual 1 is a component of society and is identified by the group membership, and 2) individual goals can be sacrificed to maintain the group harmony (Hofstede, 1980; Triandis, 1995; Oyserman, 1993; Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Oyserman, Coon & Kemmelmeier, 2002). Although the terms of individualism (IND) and collectivism (COL) have been used in a variety of studies, the ways that they were conceptualized were slightly different among various studies. Shavitt et al. (2006) suggested that there were three well-established dichotomies that were used to conceptualize individualism and collectivism. They comprised 1) national culture (e.g. Western versus Eastern cultures, such as the U.S. and Japan); 2) individual differences in cultural orientation (e.g. individualistic versus collectivistic); and 3) salient self-construal (e.g. independent versus interdependent views) (p.326). In addition, scholars have found that all these three levels of distinctions could yield similar effects on information processing and persuasion (Shavitt et al., 2006). Oyserman, Coon & Kemmelmeier (2002) summarized that the core assumption of individualism was that “individuals are independent of one another (p. 4),” whereas the core assumption of collectivism was that “groups bind and mutually obligate individuals (p. 5).” Aaker and Maheswaran (1997) revealed the attitudinal and behavioral differences among individualism and collectivism cultures. The authors stated that the self-construal in individualist cultures was defined by internal and personal attributes, whereas the self-construal in collectivist cultures was defined by family, friends or important others. Furthermore, the role of others was more salient in collectivist cultures (e.g. relationships with others can affect personal preference) than in individualist cultures. They also indicated that the values of collectivist cultures emphasized on 2 connectedness and relationship between people, whereas the values of individualist cultures focused on separateness and individuality. Additionally, people in individualist cultures would conduct certain behaviors in order to be unique, to express personal preferences, and to satisfy personal needs, whereas people in collectivist cultures, people would try to be similar to others and maintain the harmony within the group (Aaker & Maheswaran, 1997). In sum, people from individualist cultures tend to have independent self-construals. They stress the difference and importance of self, personal goals, and individuals needs. Their decisions are less likely to be influenced by others. In contrast, people from collectivist cultures tend to have interdependent self-construals. They emphasize on the importance of fitting self in with others, maintaining harmonious relationship with others, and are more responsive to other people’s preference and influences (Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Aaker, 2006; Shavitt et al., 2006). Vertical/horizontal cultures In addition, some scholars took a leap forward and discovered more distinctions in the individualist and collectivist cultures. Shavitt et al. (2006) stated that some societies were vertical (emphasizing on hierarchy), whereas as others were horizontal (focusing on equality). In other words, individualist cultures can be either horizontal or vertical. For example, the United States, Great Britain, and France are considered as countries with vertical, individualist cultures (VI). In these countries, people tend to value competition, power and achievement, and try to stand out by improving their individual status. On the other hand, in horizontal, individualist (HI) cultures (e.g. Sweden, Denmark, Norway, and Australia), people may have a preference to uniqueness and self-reliance, but they also view themselves as in equal status to others. 3 For example, Nelson & Shavitt (2002) indicated that people from the United States (VI society) placed more importance on success and achievement than people from Denmark (HI society). Moreover, studies have shown that people from horizontal, individualist cultures value the virtues of modesty (Nelson & Shavitt, 2002; Triandis & Gelfand, 1998), whereas people from vertical, individualist cultures are more concerned with being successful or having/being the best (Triandis & Gelfand, 1998). Shavitt et al. (2006) continued to argue that vertical, collectivist (VC) cultures (e.g. Korea, Japan, India, East Asian countries) focused more on the enhancement of the in-group status and compliance to the authorities. People from these countries honor the hierarchical relations with others, conforming to authorities, and trying to preserve in-group harmony. In contrast, in horizontal, collectivist (HC) cultures, such as Israeli kibbutz, the emphasis is on social appropriateness, cooperation, sociability within a framework that value egalitarian and equality (Triandis & Gelfand, 1998). Shavitt et al. (2006) has successfully enriched and refined the original individualism-collectivism split into a four-dimensional cultural distinction. In the following discussion, I will emphasize on reviewing some of the important findings in cross-cultural studies. Some of the studies may have taken the traditional IND/COL (or independent or interdependent views) perspective, whereas some may have followed the four-dimension conceptualization of culture– VI, HI, VC, HC. 2) Cultural effects on persuasion and information processing A substantial amount of studies related to cultural psychology, consumer psychology and communications have emphasized on examining whether people from 4 some cultures favor different types of message appeals; construe same information based on different factors (dispositional v. situational); or perceive similar information differently according to their cultural orientations. Some of the studies also investigated the experiences with certain emotions in different cultures and attempted to examine the effects of emotion appeals among people with distinct cultural orientations (for a review, see Oyserman, Coon & Kemmelmeier., 2002; Shavitt et al., 2006; Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Fundamental attribution error Morris and Peng (1994) conducted in a series of studies among Chinese and American participants from high schools and graduate schools to test the cultural differences of fundamental attribution error. The notion of fundamental attribution error refers to the tendency to underestimate the impact of situational factors and overestimate the role of personal and dispositional factors. In other words, people have the inclination to assume that a person’s behaviors is due to what “kind” of person he/she is rather than due to the social or environmental factors influencing him/her. The findings of Morris and Peng (1994)’s studies revealed that the effect of fundamental attribution error were culturally limited. The author suggested that “in highly collectivist cultures, such as China, persons are primarily identified as group members, they cannot freely leave groups, and they are socialized to behave according to group norms, role constraints, and situational scripts (Morris & Peng, 1994, p. 592).” Consequently, Chinese tend to explain, view and perceive things by emphasizing on situational factors. For example, when Chinese participants were asked to weigh the possible causes for murder, they emphasized greatly on situational factors (e.g. influenced 5 by violent movies; the murderer was frustrated because nobody respected him; the murderer followed the ruthless and brutal examples from Chinese Communists.) On the other hand, the authors suggested that “in highly individualist cultures, such as the United States, persons are primarily identified as individual units, they can leave groups at will, and they are socialized to behave according to personal preferences (Morris & Peng, 1994, p. 592).” As a result, American participants incline to explain, view and perceive things by emphasizing on personal factors. For example, when American participants were asked to evaluate the possible causes for murder, they stressed more on personal factors (e.g. the murderer was crazy and had mental illness and personality problems.) Cultural effects on processing cues Aaker and Maheswaran (1997, study 1) conducted an experimental study among participants from Hong Kong to investigate whether others’ opinions or group norms (i.e. consensus cues) were emphasized in collectivist cultures. They suggested that when processing new information, people from collectivist cultures paid more attentions to heuristic cues. More specifically, they found that the consensus cues (e.g. 81 percent of 300 consumers in Hong Kong think this new camera is great.) in the messages were used as a basis for evaluations regardless of motivation levels (e.g. high or low) or the valence of the attributes (e.g. positive or negative). However, the attribute information (e.g. picture quality, ease of operation, et al.) was elaborated only when the motivation was high. They further argued that “heuristic process may be a dominant mode of processing in collectivist cultures (p.321).” This study also discovered that when the consensus and attribution information was incongruent, people from collectivist cultures would discount the attribution information. 6 In addition, the authors examined the interaction effect between strength of the argument and the motivations when there were no consensus cues in the message (Aaker & Maheswaran, 1997) among Hong Kong Chinese. They found that people with low motivations showed more favorable evaluations as the amount of the attribute items in the message (heuristic cues) increased (indicating heuristic processing), whereas people with high motivations showed more positive attitudes when the arguments were stronger (indicating systematic processing). The authors concluded that the due process models “are effective in predicting and explaining persuasion effects across cultures (p. 326). In the study reviewed above (Aaker & Maheswaran, 1997), consensus information in the message was considered as a heuristic cue compared to attribute information. In another study, Aaker and Sengupta (2000) investigated another heuristic cue - “source of the product (i.e. product endorser)” - in a set of studies that included American and Hong Kong Chinese participants. More specifically, the authors revealed that when the valence of the sources and the attributes information were incongruent, American participants elaborated more on the information on the product’s attributes and neglected the information on the sources. However, the similar pattern was not discovered among Chinese participants. Additionally, for Americans, the evaluation of the product was influenced just by the attribute information (i.e. a cue attenuation strategy) under the source-attribute incongruity condition. Nonetheless, for Chinese, the evaluation of the produce was impacted by both source and attribute information (i.e. an additivity strategy) when they were incongruent (Aaker & Sengupta, 2000, study 1). The authors further indicated that Americans were more motivated to solve the source-attribution incongruity information 7 than Chinese. Therefore, the level of elaboration was higher for Americans than for Chinese and attribute information was more salient for Americans in their evaluations. During the second study, Aaker and Sengupta (2000) further investigated how the different levels of elaboration could mediate the role of cultural influence in processing incongruent information. They discovered that when the involvement was high (i.e. higher level of elaboration), both Chinese and American participants followed the same processing strategy – attribute information (i.e. a cue attenuation strategy) had greater impact for evaluations when the source-attribute information was incongruent. In the third study, the authors (Aaker & Sengupta, 2000) investigated the effects of both source cues (i.e.non-diagnostic cues) and consensus cues (i.e. diagnostic cues) among Chinese participants. They discovered that the consensus cues in the message yielded more positive evaluations than the source cues. The authors suggested that when diagnostic cues (e.g. consensus cues) were salient, people from East Asia cultures (such as China) weighed less on the attribution information no matter whether the elaboration was high or not. However, when the cues were non-diagnostic (e.g. source cues), members of East Asia cultures utilized an additivity strategy when the elaboration was low and took an attenuation strategy when the elaboration was high (Aaker and Sengupta, 2000). In sum, all of the three studies summarized by far demonstrated the different strategies employed by people from collectivist cultures and individualist cultures when processing information. When processing information, individualistic individuals have a preference on dispositional factors and emphasize on just on the primary and essential information (e.g. attribute information) (Morris & Peng, 1994; Aaker & Maheswaran, 8 1997). In contrast, collectivistic individuals show a different pattern during information processing. First, they may have a preference on situational factors (Morris & Peng, 1994). Second, when there is a conflict between primary and secondary information (e.g. source-attribute incongruity), they prefer to take consideration into both types of information (i.e. an additivity strategy). However, when the elaboration level is high, the collectivist individuals may adopt a similar cue attenuate strategy - focusing on primary attribute information - as the individualist individuals (Aaker & Maheswaran, 1997; Aaker and Sengupta, 2000). However, the effect of the cues may be different depending whether they are diagnostic or non-diagnostic cues (Aaker and Sengupta, 2000, study 3). Matching cultures with appeals Some studies found that certain persuasive appeals were compelling to some cultures but not for other cultures (for a review, see Oyserman, Coon & Kemmelmeier, 2002). For example, Han & Shavitt (1994, study 2) discovered that ads emphasizing individualist benefits were more persuasive for Americans, whereas ads emphasizing collectivists benefits were more effective for Koreans. However, this effect might be moderated by product types (e.g. personal products v. shared products). The study failed to detect a moderating role of levels of involvement in the effectiveness of different ads appeals across cultures. Another example was the study conducted by Zhang and Gelb (1996), in which the authors suggested that advertising appeals should be designed to match cultural orientations. The study discovered that more favorable attitudes toward the ad and the brand were found when the ad appeals were congruent with the cultural preferences than when they were incongruent. More specifically, Chinese subjects favored more collectivistic appeals whereas American subjects favored more individualistic appeals. 9 However, when the ad was for a private-use product (e.g. a tooth brush), both Chinese and Americans favored individualistic appeal. When the ad was for group-use product (e.g. a camera), Americans had no difference in their preference toward the two appeals, whereas Chinese preferred the collectivistic appeal. Gürhan-Canli and Maheswaran (2000) examined whether the product’s country of origin (e.g. “made in the U.S.”) would have an effect on the evaluations of the products across cultures. The results revealed that individualistic people favored more of their home country product when the product was superior to competition. On the other hand, collectivistic people showed more positive evaluations toward the home country products regardless of its superiority. The authors used a four-dimension scale to measure subjects’ cultural orientation which included VC, VI, HC, and HI. The analysis revealed that U.S. subjects were more vertically and horizontally individualists than Japanese subjects, whereas Japanese were more vertically and horizontally collectivists than American subjects. The study further suggested that advertising a product by using the country-of-origin (e.g. made in Japan or in the U.S.) strategy needs to be customized in different cultures. It seemed that both individualist and collectivist countries preferred home-made products, however, individualist cultures seemed more critical – they favored their home country’s products only if they were superior. The literature regarding culture psychology revealed that “seeking for uniqueness” was one of the core values in individualist cultures (e.g. the. U.S.), while “staying with conformity” was one of the core values in collectivist cultures (e.g. East Asian countries or Latin American countries) (Shavitt et al., 2006). Kim and Markus (1999) carried out a set of studies to investigate whether individualistic or collectivistic 10 individuals had a different preference toward uniqueness and conformity objects. The sample they used in the studies included European Americans, Asian Americans, Korean and Chinese. Overall, they found that East Asians (Korean, Chinese, and Asian Americans) had a preference in objects that represented conformity (e.g. picking a pen with a common color among five pens). In contrast, European Americans preferred the objects that denoted uniqueness (e.g. picking a pen with an uncommon color among five pens). The authors further argued that there was an interconnected relationship between the preferred culture values and people’s choices for conformity or uniqueness – “people seemed to genuinely like what their culture values (p. 791).” Choi and Miracle (2004) investigated the links between national culture, self-construals, and the effectiveness of comparative advertising among participants from Korea and the U.S. They discovered that both national cultures and the self-construals could impact the effectiveness of comparative advertising. More specifically, they found that Americans showed more positive attitudes towards the comparative ads than Korean. But the cultural difference did not yield to a main effect of purchase intention. Additionally, some studies have revealed that people from different cultures may perceive same message appeals with various meanings. For example, Aaker, Benet-Martí nez and Garolera (2001) carried out four studies to investigate different perceptions of same personalities traits embedded in consumption symbols (e.g. brands) among Japanese, Spanish and American participants. More specifically, the study found that the personality of excitement is perceived as being young and spirited across cultures. However, to Americans and Spanish, it also meant imaginativeness, uniqueness, and independence. For Japanese, excitement implied talkativeness and optimism. The 11 personality of sophistication was construed as glamorous, good looking, stylish and smooth across cultures. However, in Spain, sophistication and competence were highly associated whereas competence was a separated dimension in Japan and in the U.S.. In addition, the study found out that Japanese and Spanish both shared the harmony-oriented personality such as peacefulness, whereas American and Spanish uniquely embraced the personality such as ruggedness and passion (Aaker, Benet-Martínez, & Garolera, 2001). The authors concluded that the interpretation of the personality dimensions in the commercial brands could be shifted in different cultural contexts. In other words, “the interpretation of the meaning of a commercial brand must take into consideration the particular cultural lens through which the brand is being seen (Aaker, Benet-Martínez, & Garolera, 2001, p. 506).” Cultures and regulatory focus Lee, Aaker and Gardner (2000) conducted a series of studies to investigate how the views of independent self and interdependent self (i.e. self-construals) could interact with regulatory focus. In five studies, they demonstrated three ways to distinguish people with either independent or interdependent views of self. First, they used the Self-Construal Scales (Singelis, 1994) to measure the different self-construals among American participants. Second, they manipulated self-construal in two imaginary situations (i.e. self-construals were situationally activated) -- individual work for individual goal versus, individual work for a team goal among both Americans and East Asians. Third, they tested long-term existing self-construals in both American and East Asian cultures (i.e. self-construals were chronically accessible). The authors (Lee, Aaker & Gardner, 2000) also revealed that when in the scenario involving just one person and an individual goal (e.g. playing in a tennis match to win a 12 champion title for self), Americans thought more about themselves than they would think about others, whereas Chinese showed no difference in thinking about self versus others. When in the scenario involving others (e.g. playing a tennis match to win a title for the team), Americans tended to think more about others, while Chinese showed no increases in thoughts about others. The authors further argued that this finding showed that “the self in East Asian cultures is fundamentally intertwined with others, and thus information and thoughts about others may become activated as a function of self-activation.” Moreover, the studies (Lee, Aaker & Gardner, 2000) revealed several significant interaction effects between self-construals and regulatory focus. For example, the authors indicated that for people with an independent-self view, promotion-focused information was perceived as more important than prevention-focused information. The reverse pattern was found true for those with an interdependent view. In addition, when the chronically-accessible self-construals were consistent with the situationally-activated self-construals (e.g. Americans in a context of individual task, and Chinese in a context of team task), promotion-focused information was weighed more important among people with an independent view of self; whereas prevention-focused was weighed more important for people with an interdependent view of self. However the activation of the temporary self-construals could moderate the effect of chronically-accessible self-construals (e.g. Chinese was put in an individual event) or even reverse it (e.g. American was put in an interdependent event). Cultural effects as automatic reactions One of the recent piece published by Briley and Aaker (2006) suggested that the cultural influences on the persuasion could be an automatic and spontaneous procedure which didn’t involve much of deliberative 13 processing. They found that promotion-focused information was more effective to Americans only when the judgments were made quickly and immediately. Similarly, prevention-focused information was more effective to Chinese only when the initial and automatic reactions were counted. When the processing of information involving thoughtful elaboration, the cultural effects could be diminished. The authors concluded that “the influence of cultural knowledge on judgments varies, exerting its strongest effects when people give their immediate reactions to advertisements and its weakest effect when people deliberate when forming opinions (Briley & Aaker, 2006, p. 396).” Cultural effects on emotional responses Drawing upon the different self-construals in individualist versus collectivist cultures, Markus and Kitatyma (1991, p. 235) indicated that there were two dimensions of emotions – ego-focused and other-focused. The distinction lied in whether “the specific emotions systematically vary in the extend to which they follow from, and also foster or reinforce, an independent versus interdependent self (p. 235).” For example, happiness, anger, and pride can be considered as ego-focused emotions, primarily because they are associated with a person’s internal experience, expression and need. On the other hand, shame, guilt, and empathy can be considered as other-focused emotions, largely because they are associated with others and expressing the needs for group’s unity and harmony. For instant, Matsumoto et al. (1988) revealed that Japanese had a tendency to avoid expressing anger with the presence of closed-related others. They reported feeling anger more frequently when they were with people they didn’t know. This finding suggested that the interdependent views of Japanese prevented them from showing anger, a kind of ego-focused emotion, when they were with in-groups. On the other hand, the 14 study found that Americans and Western Europeans expressed anger more frequently with the presence of their closed-related others. This finding revealed that people with independent views demonstrated ego-focused emotions (e.g. anger) to “assert and affirm the status of self as an independent entity (Markus & Kitayama, 1991, p.237).” Kitayama & Markus (1990) conducted a research study among Japanese and American participants. The authors gave a number of emotion labels and asked the participants to indicate how often they felt those emotions in their daily lives. American participants reported that they more frequently experienced ego-focuses emotions (i.e. socially disengaged emotions) such as pride and anger than Japanese in everyday life. In contrast, Japanese revealed that they more frequently experienced other-focused emotions (i.e. socially engaged emotions) such as friendly feelings and indebtedness. This study suggested that in individualist cultures, other-focused emotions might be more accessible, while in the collectivist cultures, self-focused emotions might be more accessible. As a result, for people from different cultures (e.g. individualist v. collectivist cultures), a same experience or event can generate different types of emotions (e.g. ego-focused v. self-focused). Some studies showed the causes of experiencing same emotions were different among people from individualist cultures or collectivist cultures. For example, Stipek, Weiner, and Li (1989) revealed when Americans described the situations that would make them angry, they contributed the reasons to self and in-groups (e.g. “a friend broke his promise to me”). In contrast, Chinese described the reason they felt angry was due to others’ behaviors (e.g. “a guy on a bus did not give up a seat to an old woman.”). In addition, the authors found that Chinese were not inclined to think that being successful 15 should be a source for pride, but Americans were. When explaining their experiences with guilt, Chinese primarily reported the reason of feeling guilty was “hurting others psychologically, whereas Americans considered more about their own behaviors that made them feel guilty (e.g. “violating a law”). In a similar vein, Ellsworth (1994) conducted a study in the scenarios of winning a prize in a competitive match. The study revealed that for people from individualist cultures, they experienced more feelings of pride for being successful, whereas for those from collectivist cultures, they experienced more feelings for guilt for having been helped by others but attracting the all attention by himself. Aaker and Williams (1998) further tested the notion that whether or not people would rely on highly accessible emotional when processing information. Unexpectedly and reversely, the authors (study 1) found that Americans (individualistic individuals) showed more favorable attitudes towards empathy (an other-focused emotion) ad appeals than the pride (a self-focused emotion) ad appeals, whereas Chinese (collectivist individuals) showed more favorable attitudes toward the pride appeals than the empathy appeals. The authors (Aaker & Williams, 1998, study 2) further explored the mechanism and suggested because of the novelty of the appeals, higher level of motivations was induced to process the information. For example, for collectivistic individuals, viewing an ego-focused emotional appeal would generate a novelty effect which enhanced elaboration and led to more individual thoughts. Similarly, for individualistic individuals, an other-focused emotional appeal would be novel, elaborated more and generated more collectivist thoughts. In sum, the study revealed that collectivistic thoughts could mediate 16 the relationship between other-focused emotional appeals and the attitudes towards the appeal for people from individualist cultures. Also, individualistic thoughts could mediate the relationship between ego-focused emotional appeals and the attitudes towards the appeal for people from collectivist cultures. Ending notes In sum, numerous studies have suggested that the cultural distinctions among people could have impacts on how they perceive, understand, and process information; on how they make related evaluation, judgments and choices; and on how they react to events and experiences with different emotions. A large portion of these studies emphasized on the domains of individualist versus collectivist cultures (for a review, see Markus & Kitayma, 1991; Oyserman, Coon & Kemmelmeier, 2002; Shavitt, et al., 2006). The cultural differences among people could be detected at the national levels (e.g. Korean v. American) or the individual levels (independents v. interdependents), or could be activated by inducing situational events. Researcher have developed several sets of scales to measure the cultural differences no matter whether they are chronically accessible or temporary activated (for a review, see Shavitt, 2006). Researchers have also revealed that the personality factor of an individual (i.e. a person’s regulatory focus) may interact with cultural discrepancies. More specifically, collectivists are more prevention-focused, whereas individualists are more promotion-focused (Lee, Aaker & Gardner, 2000). In order to make a message appeal to be effective and compelling, the values embedded with the appeal should be compatible with people’s basic cultural orientations (Han & Shavitt, 1994). Moreover, the influence of cultural orientations could be moderated by people’s motivations, involvement and 17 level of elaboration (Aaker & Sengupta, 2000). Finally, the cultural effects on persuasion seem to be stronger when the judgments are formed spontaneously and immediately (Briley & Aaker, 2006). Previous literature also suggested that cultural differences could also influence people’s emotional reactions toward a same issue (Ellsworth, 1994), or lead people to experience different emotions in their daily lives (Markus and Kurokawa,1991), and make people contribute different reasons for experiencing a same emotion (Stipek, Weiner, & Lim, 1989). 18 References Aaker, J. L., & Maheswaran, D. (1997). The effect of cultural orientation on persuasion. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(3), 315–328. Aaker, J. L., & Williams, P. (1998). Empathy versus pride: The influence of emotional appeals across cultures. Journal of Consumer Research, 25(3), 241–261. Aaker, J. L., & Sengupta, J. (2000). Additivity versus attenuation: The role of culture in the resolution of information incongruity. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 9(2), 67–82. Aaker J. L., Benet-Martínez, V., & Garolera, J. (2001). Consumption symbols as carriers of culture: A study of Japanese and Spanish brand personality constructs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(3), 492-508. Aaker, J. L. (2006). Delineating culture. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 16(4), 343-347. Briley, D. A., & Aaker, J. L. (2006). Bridging the culture chasm: Ensuring that consumers are healthy, wealthy and wise. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 25(1), 53-66. Choi, Y. K., & Miracle, G. E. (2004). The effectiveness of comparative advertising in Korea and the United States: A cross-cultural and individual-level analysis. Journal of Advertising, 33(4), 75–87. Ellsworth, P. C. (1994). William James and emotion: Is a century of fame worth a century of misunderstanding? Psychological Review, 101(2), 222-229. Gürhan-Canli, Z., & Maheswaran, D. (2000). Cultural variations in country of origin effects. Journal of Marketing Research, 37(3), 309–317. Han, S.-P., & Shavitt, S. (1994). Persuasion and culture: Advertising appeals in individualistic and collectivistic societies. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 30(4), 326. Hofstede, G. H. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Kim, H. S., & Markus, H. R. (1999). Deviance or uniqueness, harmony or conformity? A 19 cultural analysis. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 77(4), 785–800. Kitayama, S., & Markus, H. R. (1990). Culture and emotion: The role of other-focused emotions. Paper presented at the 98th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Boston. Lee, A., Aaker, J. L., & Gardner, W. (2000). The pleasures and pains of distinct self-construals: The role of interdependence in regulatory focus. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 1122-1134. Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253. Matsumoto, D., Kudoh, T., Scherer, K., & Wallbott, H. (1988). Antecedents of and reactions to emotions in the United States and Japan. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 20, 92-105. Morris, M. W., & Peng, K. (1994). Culture and cause: American and Chinese attributions for social and physical events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 949-971. Nelson, M. R., & Shavitt, S. (2002). Horizontal and vertical individualism and achievement values: A multimethod examination of Denmark and the United States. Journal of Cross- Cultural Psychology, 33(5), 439–458. Oyserman, D. (1993). The lens of personhood: Viewing the self and others in a multicultural society. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(5), 993–1009. Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128(1), 3–72. Shavitt, S., Lalwani, A. K., Zhang, J., & Torelli, C. J. (2006).The horizontal/vertical distinction in cross-cultural consumer research. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 16(4), 325-356. Singelis, T. M. (1994). The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 20(5), 580-591. Stipek, D., Weiner, B. & Li, K. (1989). Testing some attribution – Emotion relations in 20 the People’s Republic of China. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 109-116. Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism & collectivism. Boulder, CO: Westview. Triandis, H. C., & Gelfand, M. J. (1998). Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(1), 118–128. Zhang, Y., & Gelb, B. D. (1996). Matching advertising appeals to culture: The influence of products’ use conditions. Journal of Advertising, 25(3), 29–46. 21