Murray_et_al_2006_Tu.. - Integrated Sustainability Analysis

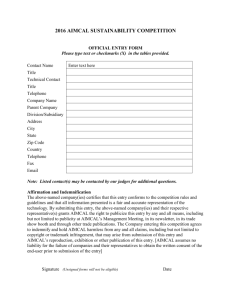

advertisement