CHANGING ORGANIZATIONAL CHARACTERISTICS AND THEIR

advertisement

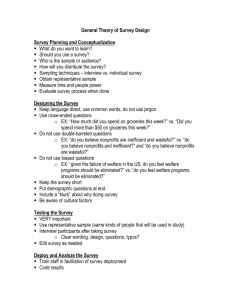

Organizational Sectors and Institutionalization of Job Training Programs: Evidences from a Longitudinal National Organizations Survey Song Yang Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice 211 Old Main University of Arkansas Fayetteville, AR 72701 *Direct all correspondence to Song Yang by email at yangw@cavern.uark.edu or by writing to Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice, 211 Old Main, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72701. I am grateful for Erin Kelly who provided and explained her dataset for this project. Introduction Institutionalization of Job Training Programs There are many explanations about training proliferation in modern organizations. The earliest and the most accepted explanation is a technical or instrumental one. Employers provide training because they provide employees with necessary skills to enhance their job performances. Leading theory in the line of work is Human Capital Theory (Becker 1993; Schwarz 1961). Employers decide whether and how much to pay for the training cost depending on the nature of training. Employers will not pay for general training that increases workers productivity inside and outside the firms because generally trained workers are likely to be poached by other employers. In contrast, employers will incur some costs for specific training that only increases the trainees’ productivity inside the firm. This is so because employers can extract some benefits in the form of enhanced productivity from specifically trained workers who have no choice but to stay in the firm. Despite the parsimony and elegance of Human Capital Theory, empirical studies often show that employers would pay for a significant portion of the provision of general skills (Bishop and Kang 1996; Loewenstein and Spletzer 1998). Using a national organizations survey, a study reports that the large majority of employers provided training that were either “to a great deal” or “to some extent” useful to other employers (Knoke and Yang 2003). Those studies have fueled some skepticism about Human Capital theory and drew research focus away from technicality considerations of job training provision. A new wave of research ensued to investigate the factors other than profit maximization that induce employers to provide training. One of the prominent arguments is institutional theory. In essence, institutional theorists argue that modern organizations operate in an increasingly complex environment and have to comply with instructions from different regulatory bodies. Earlier, Meyer and Rowan (1977) stated that organizations adopted certain practices to conform to institutional pressures. Organizations incorporate certain rules to gain legitimacy, resources, and to enhance survival prospects. Later, DiMaggio and Powell (1983) discussed three mechanisms that contextual environments exert impact on organizational in-practices. Coercive pressures are from regulatory agencies and law enforcements that impose various regulations, with which organizations have to comply. Normative pressures are professional norms that persuade organizations to adopt certain practices encouraged by professional organizations. Mimetic pressures are prevailing practices adopted by other organizations. Due to the three institutional pressures, organizations in the same field experienced structural isomorphism: their in-practice become increasingly similar. Some recent work by earlier institutional theorists applies institutional explanation to explaining some particular practices. Scott and Meyer (1991) and Monahan et al. (1994) assert that the proliferation of company job training programs in American organizations can be a nutshell that shows the process by which institutional requirements influence organizations’ inpractice. Various examples illustrate how coercive, normative, and mimetic pressures fueled a spread of job training programs. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requires that organizations provide safety training on the regular basis. The Comprehensive Education and Training Act (CETA) and the current U.S. Job Training Partnership Act provide various financial incentives (e.g. reimbursement and tax break) and to induce employers to provide basic training and retraining to unemployed workers. Professional associations and networks have been working to promulgate training practices among their members. In U.S., the most influential professional body to underwrite training is the American Society for Training and Development (ASTD), which has a large number of local chapters and hosts conferences and workshops to stimulate training provisions. Organizations, when facing uncertainties, are also likely to imitate practices adopted in other workplaces. The quick diffusion of some innovative work practices such as work quality of work life and quality circle reflects some of the mimetic effects. Irrespectively of the efficacy of those work practices, organizations adopt those to enhance legitimacy, to show their willingness to improve work quality, to gain motivation from their workforce and to achieve “nice” fit with its environment (DiMaggio and Powell 1983). An empirical study investigates details of the mimetic process in charitable organizations: organizations are much likely to mimic other organizations, to which they have network ties via boundary-spanning personnel (Galaskiewicz and Wasserman 1989). Although so far there is no empirical evidence relating job training and organizational mimetic behavior, it is highly plausible to hypothesize that mimetic behavior is one of the major propellers for the diffusion of training programs in modern organizations. As one study shows, organizations rarely define concrete goals, design training programs, or assess their effectiveness (Monahan et al. 1994). Instead, organizations establish their training programs through imitation and take its efficacy on faith. H1: The greater the institutional pressure organizations face, being it coercive, mimetic or normative, the more likely that the organizations to adopt job training programs. Differentials in Job Training Institutionalization: the Importance of Organizational Sector Every theory has scope condition (). Institutional theory is no exception to this rule. A recent review perceptively points out the weakness of institutional theory: a lack of scope condition undermines the theory by producing a loose collection of incompatible propositions (Haveman 1998). As institutional theorists attempt to explain everything with various irreconcilable propositions, they end up explaining nothing (Haveman 1998: 478). Thus scholar proposes that institutional theorists reach paradigm consensus to remedy the situation. Because causal mechanisms vary across different institutional settings, one of the steps proposed to reach such consensus is to specify when and where the institutionalization process operates and when and where institutional actors are potent (Haveman 1998). One major question emerged in response to the quest of specifying a domain where institutional effects are nontrivial. That is: how to meaningfully distinguish different organizations and to compare among them with regard to the impact of institutional pressures on organizational adoption of certain practices? An important work recently emerged that discussed organizational differentiations across different sectors (Frumkin and Galaskiewicz forthcoming). A crucial standard for placing organizations into different sectors is the measurement of organizational outputs. For-profit firms operate on profit maximization and measured with a whole array of clear-cut indices such as profits, share price, earnings, market share, and growth. Owners and shareholders for business firms aggressively assert control, demand returns to their investment, and squarely dismiss executives whose performances fall below certain threshold. Generally speaking, there is little ambiguity when it comes down to measure how firms are performing, given the whole set of largely quantified and easily interpretable measurement data. In contrast, nonprofit organizations and governmental agencies operate on a different system. Because nonprofits and governmental agencies do not have owners who have material interest in the performance, they are operating under so-called non-distribution constraint (Hansmann 1980). That is: unlike business firms that can distribute their profits among stockholders, nonprofits and governmental agencies are not allowed to make a distribute, but must retain any earnings. Furthermore, nonprofits and governmental agencies produce outputs that are considerably difficult to measure and to interpret. Several factors contribute to such difficulty. Compared to business firms, nonprofits and governmental agencies are more likely to embrace a broad range of goals, many of which are ambiguous and not entirely consistent with each other. There lacks of a set of consistent and clear-cut standard to measure the accomplishments of those goals. Also because of the nature of the goods and services produced by nonprofits and governmental agencies, their outputs are indivisible (Moore 1995). Little funding and institutional demand exists for serious assessment of their performances. Especially for governmental agencies, their outputs are not measurable until far in the future and detailed information on how they process task is not under the same kind of scrutiny as business firms. Compared to for-profit firms, the relatively short of unambiguous measures of performance and much sporadic monitoring for governments and nonprofits do not necessarily produce more freedom in their operation. Delays or malfunctions of governments and nonprofits are frequent headlines on major news medias. The recent response made by the commissionaire of USCIS (US Citizenship and Immigration Services) with regards to backlog reduction vividly illustrates that governments sometimes can be particularly vulnerable to outside criticism. For governments and nonprofits, a lack of performance measures and loosely coupled goals only mean they are facing more difficult task to justify the way they operate than for-profit firms. Often times, governments and nonprofits turn to external referents to legitimate their acts (Frumkin and Galaskiewicz forthcoming). Therefore, to the extend various institutional pressures affect organizational internal practices, they exert greater impact on practices of governments and nonprofits than do they on for-profit firms. In particular to organization job training programs, the legal requirement by OSHA, the norms promulgated by ASTD, and the effect of imitating other organizations with training programs may exert stronger impact on the training programs for governments and nonprofits than they do to for-profit. As previously noted, due to goal ambiguity and performance measure difficulty, governments and nonprofits are more eager to obtain outside endorsement to legitimize their procedures and operations. As institutional conformists can garner various benefits such as reputation, legitimacy, and eligibility for grants (DiMaggio and Powell 1983), they tend to benefit governments and nonprofits more than they do for the for-profit firms. Thus, to the extent that institutional pressures may instigate organizations to provide job training, governments and nonprofits are more attuned to those influences than are for-profit firms. H2: The Institutional impact on organization training provision is stronger for governmental agencies and nonprofit organizations than it is for for-profit firms. Data To investigate the diffusion and determination of company job training programs, I use the 1997 National Organizations Survey of Human Resources Policies. The principal investigators for this survey are Frank Dobbin and Erin Kelly (for detailed documentation of this dataset, see Kelly 2003). The University of Maryland Survey Research Center conducted interviews with selected organizations. The sampling frame was from the well-known Dun and Bradstreet Market Identifier dataset. Dun and Bradstreet initially provided 1,714 organizations, among which 1,478 establishments with at least 50 employees were declared as eligible for the study. This list of 1,478 establishments was stratified by size and industry prior to random sampling selection, which later produced a randomly selected 695 establishments. Interviewers first sent letters out to the 695 establishments, followed by telephone interviews. Totally 389 establishments completed the telephone interviews, which yields an acceptable response rate of 56 percent (389/695 = 56%). The research is designed to study the diffusion of various human resources programs, particularly work family practices, of U.S. organizations over the past 30 to 40 years. Interviewers asked establishments’ human resources managers or functional equivalent personnel who are knowledgeable of the history of the human resources policies. To analyze and compare across sectors, researchers over-sampled public, non-profit, or large organizations. Researchers used a minimum 50 employees as threshold to select establishments because those with less than 50 workers are less likely to have written documents of various human resource practices. Consequently, the sample contains employers more likely to have formalized human resources policies than the general population of employers. To trace the diffusion of various human resource practices, the interviewers asked organizational respondents to supply retrospective, over-time data on key variables. For those variables, interviewers asked if the work establishment had ever provided or offered that program. If answered yes, they continued to ask when the program was initiated and when, if ever, it was discontinued. I used those responses to establish a training timeline, in which organizations will have 0 if they had never adopted job training programs till 1997, or 1 for the year when the organization first adopted the program. Because the survey only asked the number of employees at several points -- the year the establishment was founded, 1967, 1977, 1987, and 1997 -- I interpolated the number of employees for other years with the available data. In particular, if an organization reported an increase in the number of workers from 100 workers in 1967 to 110 workers in 1977, I will divide the net increase of 10 workers by the total interval of 10 years and added it with the workers’ number of 1967. Because the survey also asked the organizations whether they have experienced sudden increase or decrease in their workforce, and if so, when and how many workers increased or decreased, I used those responses to fine-tune the interpolation of worker size. For example, if an organization reports a sudden decrease of 200 workers in 1995, the worker size for that organization in 1995 should be its predicted size minus 200 workers. Method The statistical method used in this analysis of company adoption of job training program is discrete-time event history method. Event history method is concerned with the patterns and correlates of the occurrences of events such as marriages, divorces, crimes, arrests, deaths or merger of organizations, and, of course, organizational adoption of training programs (for detailed introduction to event history analysis, see Allison 1984, 1995; and Yamaguchi 1991). Event history analyses encompass two types of models: discrete-time model and continuous time model. The difference between the two is that discrete-time model assumes that time can be disaggregated into discrete units such as weeks, months, and years, whereas continuous-time model assumes time is measured continuously (Allison 1984). Because the survey measured the first adoption of training program based on years, I used logistic regression of discrete-time event history analysis to analyze the determinants of company job training programs. In particular, the model follows log (Pit /(1- Pit)) = t + 1 Xit1 + 2 Xit2 + …… k Xitk where Pit denotes the conditional probability that the unit (individuals, organizations, nations etc) i has an event at time t, given that an event has not already occurred to the unit. And t denotes discrete points in time (year in this study) that ranges from 1 to N. Measures Training provided to core workers (core training) is the dependent variable, measured by a series of questionnaire items: “Apart from on-the-job training, has your organization ever provided core workers with formal training?” If yes, “in what year was this training first provided?” “Is the training still provided?” If no, “in what year was the training program discontinued?” Researchers have defined core workers as those workers with the job title that has the most employees at the establishment (Dobbin and Kelly 1997). Using the responses to those items, I constructed a timeline that describes when organizations first started their job training programs. In the logistic discrete-time model of event history analyses, I arbitrarily established a time frame from 1967 to 1997 mainly because that’s when most events are recorded into the survey. Organizations are entered into the sample provided that they were founded before 1967 and they had not adopted formal training programs by 1967 (thus they are still at risk to adopting the programs). Totally 132 organizations were entered into the logistic discrete-time regression model, which include 73 organizations that did not adopt the training program till 1997 (right censored), and 59 organizations that were founded before 1967 and adopted training programs during the span from 1967 to 1997. The following paragraphs describe construction of our independent variables. Organizational institutionalization is one of the key independent variables. It encompasses three dimensions: coercive, mimetic, and normative institutionalization. All the questionnaire items asking about these institutionalization measures follow the same routine: first asking whether organizations have received certain programs/practices, if yes, when organizations first received such programs/practices, was the programs still continue? If no, when was it discontinued? In particular, coercive institutionalization was captured with a question asking “has the organization even had a compliance review by the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs?” Mimetic institutionalization was measured with two items “has organizations ever used outside human resources consultants?” and “has the organization ever consulted an attorney for its human resources matters?” Normative institutionalization was indicated by “is your human resources executive a member of any professional association?” Using those responses, I produced a chronology that documents the spread of various institutional pressures. Organization unionization was measured with the same routine as that for institutionalization, with a questionnaire item asking “are core workers covered by a collective bargaining agreement?” Organizational sector is another key independent variable, measured with their SIC (Standardized Industrial Classification) codes (http://www.osha.gov/pls/imis/sic_manual.html). Based on their industries, I re-categorize them into three groups: group 1 (SIC code from 2011 to 7399) includes manufacturers and business service providers. These are for-profit firms facing stiff financial constraints and rigorous outcome assessment from internal agents and external investors and corporate communities. Group 2 (SIC code from 8011 to 8399) includes health and social services. Although those organizations do not face the same financial constraints as the for-profit firms, they commonly have tight budgets. Group 3 (SIC code from 9111 to 9199) includes governmental agencies which are not only the objects of, but also, in some occasions, catalyst to institutional pressures (Frumkin and Galaskiewicz, forthcoming). Organization age is measured by taking nature log of the actual age of the organization, calculated by subtracting the year the establishment opened from the year the organization first adopted the training programs. Organizations core workers are classified according to their occupations with the three-digit 1980 Census Occupational Category, established by U.S. Bureau of the Census (http://webapp.icpsr.umich.edu/GSS/rnd1998/appendix/occu1980.htm). In particular, occupational codes from 001 to 037 are categorized as managerial occupations (managers and supervisors), 043 to 235 are grouped together as professional/technical occupations (engineers and teachers), 243 to 389 are classified as low white collar occupation (sales and clericals), and the rest are categorized together as manual labor occupations (craftsmen, operatives, laborers, services and farm workers). Organization type is measured by asking “is this establishment an independent organization (1), a branch or local office of a larger organization (2), or the headquarter for a multi-establishment organization (3: the reference group in the regression)?” As noted before, the survey only asked organizations their women and minority percentage at several discrete points in the history: the percentages for women and minority during the year when the organizations were founded, 1967, 1977, 1987, and 1997. Thus I used the same method as used in estimates of organization size to interpolate those percentages for the years not covered in the survey. Findings With a unique longitudinal dataset of national organizations survey, I investigate the proliferation of training programs and how organizations respond differently to institutionalizations. To document the process in which job training program diffuses among different organizations, I compute the percentage of organizations providing job training during several historical periods, using the number of organizations with training program divided by the total number of organizations alive during the time period. For example, prior to WWII, totally 12 establishments had core worker training programs among the 116 organizations, which were alive then, producing a percentage of 10.34. In contrast, 266 organizations among the total 389 establishments adopted training programs from 1990 to 1997, producing an adoption rate of 68.38%. I then disaggregate the sample into three types: for-profit firms, nonprofits, and governmental agencies. Figure 1 shows that in general American workplaces, regardless of their sectors, have increasingly adopted job training programs. More strikingly, some discernible disparities emerged among organizations in the speed of such proliferation. For-profit manufacturers and private firms, indicated by the line of “manufacturers” in the graph, started almost at the same level as governmental agencies in the proportion of organizations with training program before WWII. But the rate of increase in the proportion of organizations with training since then is lower for manufacturers and business firms than it is for governmental agencies. Such a gap has been increasingly widened since 1960s that by 1997, more than 78 percent of governmental agencies have adopted job training programs, in contrast to only 63 percent of manufacturers and firms that did so. In contrast, the diffusion of job training programs among nonprofit organizations took a different route. Before WWII, relatively fewer nonprofit organizations adopted training programs than governmental agencies and for-profit firms. But the rate of adoption of training programs has been drastically increasing since 1960s. By 1970s, the percentage of nonprofit organizations with training programs exceeded that of manufacturers and business firms. During the 1990s the rate of increase in the number of organizations with training programs in nonprofits has been slightly declining. By 1997, more than 68 percent of nonprofit organizations adopted job training programs, which is higher than for-profit firms (63 percent) but lower than governmental agencies (78 percent). To explain the diffusion of job training programs among a diverse set of organizations from 1967 to 1997, I conduct logistic regression with a longitudinal dataset, which is one of the discrete-time event history analysis techniques (Allison 1984; Allison 1995). Table 2 shows the results. Be noted that the valid cases indicate the total number of organization-year in the dataset. Although I have totally 132 organizations eligible for the analysis because they are founded before 1967 and did not provide training to core workers before then (they are still at risk of providing such training), each organization can contribute to multiple records depending on which year they provide core worker training during the span of 1967 to 1997. In support of H1 that institutional pressures instigate organizational job training programs, table 2 shows that for the entire sample, organizations using external human resources (HR) attorney, one of the measures for the mimetic institutional effect, have 298% (Exponential (1.382) – 1 = 2.98) higher odds to provide core worker training than are organizations without an external HR attorney. In the control variables, each unit of increase in organization size increases the odds of providing core worker training by 22 percent (Exponential (0.198) – 1 = 0.22). To investigate how institutional impact on organization core worker training varies across different organizational sectors, I disaggregate the sample into three sub-sample: governments, nonprofits, and for-profits and conduct regression analyses separately for each sample at a time. Table 2 shows striking results that support H2. The use of external HR attorney exerts the strongest impact on the training programs of governments but weakest impact on for-profit firms. The effect on nonprofits falls in the middle of those on governments and for-profits. Compared to government agencies without external HR attorney, governments using external HR attorney are more than six times more likely (Exponential (1.957) – 1 = 6.07) to provide core worker training than governments without external HR attorney. In contrast, firms with external HR attorney are only less than three times more likely (Exponential (1.033) – 1 = 2.81) to provide core worker training than their peers without external HR attorney. To ascertain whether the differences in regression coefficients are significant across the three organization sectors, I applied the statistical analyses of Comparisons Across Populations (Knoke et al. 2002: 278-281). The diagonal values in table 3 are the regression coefficients of external HR attorney for each sub-sample in table 2. The numbers in cell entries that coordinate two sectors are the difference of their coefficients. Table 3 shows that among the three comparisons, the difference between governments and for-profit is significant. The impact of external HR attorney on core worker training provision is significantly stronger for governments than it is for for-profit firms. Those results indicate that to the extent having an external HR attorney can induce organizations to adopt formal training to their core workers; governmental agencies are much more responsive to the effect than for-profit firms. Discussion Modern organizations operate in a much complex environment that defies easy explanation. Institutional theorists, by emphasizing legitimacy (DiMaggio and Powell 1983; Scott and Meyer 1994; Scott 1998), structural decoupling, ceremonial myth and symbols (Meyer and Rowan 1977), have redirected the focus of organization studies. Representing a major departure from competing theories such as transaction costs economics (Williamson 1981) and resource dependence theory (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978), institutional theorists insist that organizations often act without conducting the simple cost-benefit analysis. The apparent deviant behaviors, however, are perfectly rational if one considers the operating environments that constantly impose various norms, sanctions, regulations, and persuasions on organizational internal practices (Scott and Meyer 1994). By complying with those norms and regulations, conformist organizations achieve a better fit with their environment, gain reputations, smooth transactions, and attract talented individuals (DiMaggio and Powell 1983). Using a national longitudinal dataset of a diverse set of American workplaces, this study established that organizations yield to institutional pressures by adopting training programs to their core workers. Furthermore, the study shows that organizations respond to institutional pressures to different degrees. Governmental agencies are the most vulnerable to the institutional influences, compared to nonprofits and for-profit firms. This finding strikingly concurs with theoretical discussions (Scott and Meyer 1994) and empirical results (Frumkin and Galaskiewicz forthcoming) that institutional effects do not affect organizations the same. Although it remains to be seen whether the patterns shown here are also applicable to other organizational in-practice, this research alerts institutional scholars to reassess the roles institutionalization can play. To various organizations, the benefits of gaining legitimacy and reputation for being an institutional conformist are evaluated very differently. For-profit firms, with clearly pre-set goals and highly measurable outcomes, weigh heavily on the efficacy but pay less attention to institutional influences when it comes down to establish a program. In contrast, governmental agencies, with ambiguous goals and less measurable products are much responsive to institutional pressures to obtain their much-needed benefits of legitimacy and reputation. Institutional theorists open a new phase in organizational analyses by drawing attention away from traditional explanation of organizational behaviors based on atomic and economic rational models. Modern organizations are embedded in an increasingly complex environment that fundamentally changes many taken-for-granted organizational practices. This study contributes to institutional theory by delineating an organizational sector where institutional effects are most potent. Governmental agencies are not only the makers and advocators of institutional regulations but also the most enthusiastic responders to the institutional forces. Although in this regard, more analyses are needed to confirm the assertion, this study serves one step further toward the ambitious goal of achieving paradigm consensus among institutional scholars. 100.0 90.0 80.0 70.0 60.0 50.0 40.0 All orgs 30.0 For-prof it 20.0 Nonprof it 10.0 0.0 Government Before 1945 1960-1969 1945-1959 1980-1989 1970-1979 1990-1997 YEAR Figure: Proliferation of Job Training Programs among U.S. Organizations Table 2: Unstandardized Coefficients of Logistic Regression of Organization Core Training Provision 1967-1997: Discrete-Time Model of Event History Analysis Constant All -5.976*** (.828) Governments -6.928*** (1.829) Services -6.967** (2.267) Manufacturers -6.998*** (1.532) .240 (.325) .529 (.380) ______ _______ _______ _______ _______ _______ _______ _______ _______ _______ -.041 (.385) .161 (.276) -.069 (.306) 1.382*** (.340) -.560 (.731) .198 (.487) .366 (.504) 1.957*** (.312) .088 (1.687) -.181 (.607) -.399 (.871) 1.427* (.681) -.444 (.670) .315 (.529) -1.010 (.670) 1.033** (.324) .127 (.158) .198* (.093) -.151 (.302) .192 (.410) -.249 (.396) -.080 (.347) _____ .012 (.240) .441 (.180) .037 (.512) -.367 (.703) .776 (.905) -.892 (.629) _____ 1.116 (.594) -.073 (.185) -1.031 (.779) -.048 (1.243) -.600 (.758) -.352 (1.258) _____ -.014 (.346) .369 (.210) .216 (.661) .830 (.711) -.328 (.977) .894 (.632) _____ 42***(12) 2,067 18*(10) 636 9(10) 470 28**(10) 961 Organization Sectors Government Agencies (tc) Health or Social Services (tc) Manufacturers or Business Firms (REF. and tc) Institutionalization Federal compliance (coercive, tv) Professional Association (normative, tv) External HR Consultant (Mimetic, tv) External HR Attorney (Mimetic, tv) Independent Controls Organization age (tv) Organization Size (tv) Unionization (tv) Core occupation (managerial, tc) Core occupation (professional/technical, tc) Core occupation (low white-collar, tc) Core occupation (REF.: manual labor, tc) χ2 (df) Valid cases (year-establishment) *p < .05, **P < .01 *** p<.001 (two-tail test) Numbers in parenthesis are standard errors Table 3: Across-Section Comparison of Unstandardized Coefficients of External HR Attorney on Organization Core Training Provision Governments Nonprofits For-profits Governments 1.957*** (.312) 0.530 (.750) 0.924* (0.450) Nonprofits _________ For-profits _________ 1.427* (.681) 0.394 (0.754) _________ *p < .05, **P < .01 *** p<.001 (two-tail test) Numbers in parenthesis are standard errors 1.033*** (.324)