Cooperation between women`s organisation

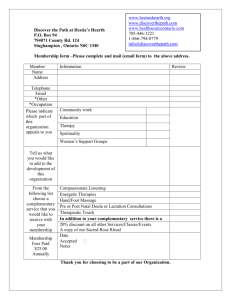

advertisement

Global Forum II, Nurturing the Future: Challenges for Maternal Lactation in the 21st Century World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action – WABA Tanzania, September 2002 Cooperation between women’s organizations and alliances for maternal lactation at a global scale: a strategy proposal Dr. Ana María Pizarro Women’s Health Network for Latin America and the Caribbean Area SI MUJER. Nicaragua “With legal, economic, practical and emotional support, mothers should be able to breastfeed their infants in an exclusive way between the age of 4 and 6 months, and even longer…” This assertion is quoted from the 8th paragraph of El Cairo’s Action Program1, which is. Needless to say that this paragraph was not brandished by fundamentalists in their violent campaign against women’s rights. Furthermore, and since the pledges taken 8 years before could not be fulfilled, El Cairo reminds us that “Governments should promote public information about the advantages of maternal lactation; the health workers should receive training on the proper standards for maternal lactation and countries should envisage the adequate means aiming at a full application of the WHO’s International Code for Marketing of Substitute Products for Breast milk”. The International Women’s Movement, which dealt with women’s empowerment, their political participation in decision-taking instances, sexual rights as well as reproductive rights, education, sexuality, comprehensive health, work, migrations, lacks of capacities and the impact of sexual, family, economic or political violence – among other key topics – has not yet tackled the true relevance of maternal lactation up to its real extent. As a consequence, it seems that this is a pending item on both the national and international agendas. The common points However, the International Women’s Health Movement has made a series of progress on key issues that facilitate a strategic alliance in favor of maternal lactation, since all the 1 Health, Mortality and Morbidity. Page 55. Report of the Conference on Population and Development. September 1994. 1 factors related to this right – the women’s as well as the infants’ – have been clearly stated and advocated. This is why we are demanding the right to infants’ and women’s survival in legal, economic, emotional and nutritional conditions that all point towards easier reproductive, birthing, upbringing and development processes of children who are welcomed into our societies. A global debate on the HIV/AIDS pandemic has somewhat darkened the situation on the maternal lactation advocacy front. In this field, the international women’s movement has opened the way by asking firmly to the international organizations, cooperation agencies, authorities and governments, men and women working in health programs and society as a whole, to take an active and responsible part in the fight for the women and their infants to exercise their: Right to a sustainable health and decent living standards Right to reliable information Right to counseling and confidentiality Right to true access to good quality health services Right not to be an object of experimentation The International Women’s Health Movement has recently expressed its view in Toronto2, on key issues that affect the living standards of women and infants. In the Latin American Declaration against fundamentalisms and neoliberal globalization, we have committed ourselves to: Explicitly opposing to the neoliberal policies and development models, established by our governments and which appear to be detrimental to the quality of life and to the health of women and children of the whole world. Systematically denouncing all the attempts and policies that aim at colonizing the bodies of women, violating their rights and depriving them of their exercise of citizenship. Facing up to the reforms set up in the health sector as well as their impact on the comprehensive health of women. Eliminating the traditional practices that go against the women’s and their infants’ human rights. The International Women’s Movement has been denouncing the effects of poverty and social exclusion on women, as well as the consequences of the AIDS pandemic. Since the issue of maternal lactation is currently acquiring specific relevance and in view of the recommendations put forward by international organizations as regards lactation in extraordinary cases, we think that there is a number of contradictions that need to be solved, for instance: The research works report different figures about the probabilities for an HIVpositive woman to transmit the virus to the fetus or the newborn during 2 9th International Meeting on Women and Health. Toronto, Canada, bet. 12th and 16th August. 2 pregnancy, delivery or lactation, especially if the latter is protracted. The reports show considerably different findings, since vertical transmission is ranged between 7%3 and 45%4 in so-called “developing” countries. Some other sources give a figure of 50% for the latter. Maternal lactation is said to make up for 3%5 to 4%6 of all the cases of vertical transmission, although other sources report a 14%7 to 19%8 range. To this respect, in 1998, the International Communities of Women Living with HIV/AIDS9 (ICW), hoping that UNAIDS would welcome favorably these recommendations, expressed its stance about the priority issues which affect the women living with the virus and that are still in need of a solution. Some urgent research needs to be carried out on maternal lactation, since mothers have a right to know that it can be a means of transmission as well as to be informed of the research done to this respect. Mothers also are entitled to know about other alternatives, excluding commercial formulas. The UNAIDS recommendations include an HIV screening test to all pregnant women. The ICW Living with HIV/AIDS are totally opposed to compulsory tests – in all theirs forms – for HIV antibodies detection. This does not mean that UNAIDS intents to conduct compulsory tests, but that there is a risk of distorted interpretation – actually disseminated – of health programs led in poor countries. When the results of the screening tests are available, pregnant women can really be discriminated against. There is no generally agreed recommendation applicable in relation to breastfeeding in the case of HIV-positive mothers. A lot of programs launched by UNAIDS in Africa and Asia promote maternal lactation since the proven risks of neonatal death caused by diarrhea, malnutrition or respiratory conditions are both considerable and proven to be higher. For instance, in the Philippines, research has shown that the risk of diarrhea is 17 times as high in the case of infants aged between 0 and 2 years who were not breastfed10. However, a series of agreements have also been reached in Latin America11, compiled into an Action Agenda for the AIDS/ETS National Programs. These 3 HIV Mother-to-Child Transmission. IBFAN, 2001. Maternal Lactation and HIV/AIDS. Global Campaign against AIDS, 1997. Source : UNAIDS. 5 IBID #1. 6 Maternal Lactation and HIV/AIDS, frequently asked questions. Linkages, May 2001. 7 IBID #5. 8 Overview of maternal lactation and HIV transmission in Latin America. José Izazola Licea. SIDALAC. 1998. 9 12th Global Conference on AIDS. June 1998, Quoted in Women, Vulnerability and HIV/AIDS. From the point of view of the Human Rights. Women-Health Newsletters #3. Women’s Health Network for Latin America and the Caribbean Area. 10 Popkin et al. 1990. IBID #7. 11 Meeting on HIV transmission through maternal lactation, Brasilia, Brazil, November 1998. 4 3 agreements recommend to ”counter-indicate maternal lactation for HIV-positive women and provide them with breast milk substitutes”. Such a contradiction must be solved and the messages aimed at health workers and the mothers themselves must be simplified and submitted to homogeneous criteria, applicable to each local reality. The chances to have access to HIV screening tests are very limited in the health services of poor countries. There is also a shortage of services aimed at guaranteeing proper counseling to HIV-positive women. And the situation gets even more complex when it is about counseling on lactation in the case of HIVpositive pregnant women. Another dilemma is the recommendation for the health services to provide HIVpositive women with antiretroviral medication. A vast majority of health budgets does not include this type of medicines, quite costly because of the voracity of the market. False hopes are being created surrounding health care for the affected population. While a high percentage of infants are born HIV-positive. And to finish off the list of concerns, one must take into account the impact of health programs that recommend shifting from maternal lactation to breast milk substitutes. Generally, such programs have not the necessary resources to distribute the substitutes, which generates dissatisfaction as well as a risk of malnutrition and neonatal death. The ethical dilemmas of experimentation regarding pregnancy, HIV and lactation must also been taken into consideration. To this respect, the ICW are opposed to the tests using placebo-based controls, since studies have revealed the efficiency of the drugs used in the tests. What is more, the ICW advocate for a protection and preservation of the women’s rights as well as for the dignity of their infants and children12. The need to solve those issues clearly shows that priority must be given to creating an alliance between WABA, other maternal lactation advocacy sectors and the organizations that constitute the international health movement. The Women’s Health Network for Latin America and the Caribbean Area, with headquarters in Chile, as well as the Women’s Global Network for Reproductive Rights, with headquarters in Amsterdam, are strongly committed to strengthening, developing and creating alliances with other groups and organizations, in order to defend the rights and fields that have been conquered, as well as to make progress towards enlarging those rights and guaranteeing respect of democracy and citizenship for all women.”13 12 IBID #8. Declaration made by the Latin American women’s groups and organizations during the 9 th International Meeting on Women and Health, Toronto, August 2002. 13 4