The Nature and Goals of Care in Medical Oncology

The Nature and Goals of Care in Medical Oncology

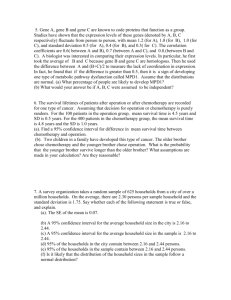

Goals and Judgements in Early Disease ......................................................... 9

Goals and Judgements in Advanced Disease .................................................. 9

Nature and Goals of Treatment

Forms of Therapy

Medical oncologists use a number of classes of drugs. These include those strictly classified as chemotherapy (also referred to as cytotoxics , that is drugs that kill or damage cancer cells), together with hormonal therapy, and supportive care drugs (e.g. drugs for pain relief, nausea, diarrhoea, loss of appetite, mood disturbance). Chemotherapy drugs are generally used exclusively by medical oncologists. The other drugs may be used by other medical specialties working alongside medical oncologists (e.g. radiation oncologists, palliative care physicians).

The main health professionals that work in cancer care are medical oncologists (primary focus being the use of chemotherapy drugs and the medical care of patients with cancer), radiation oncologists (focussing on the use of radiation), surgeons including surgical oncologists (focussing on the surgical removal of tumours a

and relief of complications), palliative care physicians (focussing on symptom control and end of life issues) and supportive care professionals (e.g. social workers, psychologists, focussing on emotional, psychosocial and spiritual support of the patient). Many of these functions overlap and the various professionals work together in a multidisciplinary environment. Nurses work in all these areas, as do many other allied disciplines, e.g. physiotherapists, occupational therapists etc. a Although sometimes used interchangeably, cancer refers to the overall process of uncontrolled growth and spread, while tumour refers to a specific mass or lump of cancer, usually at the site of its origin

(primary tumour). Another term for uncontrolled growth is neoplasia .

Of the various interventions, several or all may be used over the time that the patient’s cancer is under treatment, increasingly simultaneously. An example of this would be a patient with a cancer of the rectum who may have the primary tumour removed surgically, but also receive chemotherapy and radiation, (most commonly given together at the same time), to increase the chances of long term control of the cancer.

An important distinction between chemotherapy on the one hand, and surgery or radiation on the other, is the scope of their effect on cancer. Surgery and radiation are referred to as local forms of treatment, because they deal with cancers in a defined area, for instance removing a tumour from the breast, and then radiating the remaining breast tissue. On the other hand chemotherapy is considered a systemic form of therapy, because it affects the entire system (body). The drug is distributed in the blood to all the tissues of the body.

Outcomes and Goals

The nature of the outcomes need to be separated from the goals of treatment. Outcomes cover what is possible or probable, while goals addresses specific plans.

The goals of treatment need to be considered in the context of the overall care of the patient, but are generally based on the available scientific evidence, on the patient’s individual preferences and values, and to some extent the available resources. The goals are likely to change with circumstances as the patient passes through the different stages of the disease and its care.

Stage

The ‘stage’ of disease, is a way of describing the extent of a cancer. This is often expressed numerically from I-IV (1-4), with Stage I being the earliest stage where the tumour is still very localised and Stage IV being the most extensive. The exact definitions of stage will vary between different forms of cancer. More generally, the stage is expressed as early or advanced

. ‘Early’ cancer refers to a tumour that is not too extensive and has not spread, while ‘advanced’ implies cancer that has spread. Thus stages I and II might be considered to represent an earlier stage than the more advanced disease seen in stages III and IV. When we refer to a cancer spreading, we mean it has broken away from its site of origin (primary tumour) and is now growing in other parts of the body.

The process of spreading from a primary tumour is referred to as ‘metastasis’ and the new, or secondary tumours are known as ‘metastases’. Chemotherapy being a ‘systemic’ therapy has the capability of reaching all tumours in the body, not just a localised primary tumour.

A third, and equally important category, is referred to as locally advanced cancer. While not always precisely defined, this means that it is extensive, but has not spread, is causing considerable symptoms, usually from pressure on or invasion of, surrounding structures or organs, and is unlikely to be controlled by local means of therapy alone (radiation or surgery).

Outcomes

Cancer care is sometimes wrongly described in terms of being either curative on the one hand, or non-curative or palliative on the other. With the evolution of forms of care and understanding of the cancer process this simple division has become untenable. This brings the thinking into line with that of other chronic diseases such as diabetes, or heart disease.

Curability

The known probability of cure may vary from virtually negligible or low (e.g. breast, lung, or bowel) to relatively high (e.g. testicular cancer) depending on the nature of the cancer, its stage (degree to which it has grown), and patient factors (sex, age, other medical conditions).

Estimates of the chances of cure in an individual are also likely to change over time as the circumstances change for that person and time passes. Terms that may also be used include reference to the probability of cure, such as a low-probability or high-probability.

Cure is hard to define,

1

since it implies knowledge of the future. Therefore physicians increasingly are avoiding it, preferring terms like ‘controlled’ in a similar way to referring to treating a condition like diabetes with insulin. Obviously ‘cure’ is a time dependent phenomenon, in that it assumes a patient lives long enough to eventually succumb to some other disease process, without evidence of cancer. More useful is to provide a numerical range of probabilities, e.g. 40-50% chance of cure. A patient may be apparently free of disease, but can only be given a statistical probability of being ‘cured’ at any point in time. Some physicians find it helpful to distinguish between dying of cancer, or dying with cancer. For instance an elderly man may develop prostate cancer which is initially controlled but not cured, and eventually dies of heart disease.

However in some cancers statistical evidence suggests that the ultimate probability of cure may become more predictable after the passage of a certain period of time. For instance five years after the surgical removal of a large bowel cancer, with or without additional chemotherapy, the chances of the tumour re-growing a

are very low if there is no evidence of cancer at that time. Conversely a patient with breast cancer may appear to be well at five years but remains at risk of re-growth over their entire lifetime.

Range of outcomes

The possible outcomes include relief of symptoms, shrinkage of the tumour, delay in tumour growth, stabilisation of a rapidly growing tumour, and cure.

There are other terms that are used in describing the outcome of care. Some of these have become standardised to improve uniform description in the medical literature. a Often described as ‘recurrence’ or ‘relapse’, particularly if the patient has been free of detectable disease prior to this.

Response

With regards to objective measurements of tumour shrinkage (response) or growth

(progression), outcomes are generally classified into four types.

(i) Complete Response: No evidence of cancer a

(ii) Partial Response: At least 50% improvement

(iii) No Change (or Stable Disease): Less than 25% larger, no change or less than

50% improvement

(iv) Progressive Disease: More than 25% larger (continued growth)

Patients in the first two groups, whose cancers show an objective response (Complete or

Partial) are said to be responders, and to be in either a complete or partial remission.

Patients in the third category are said to be ‘stable’. The term ‘tumour control’ is often used to describe the proportion of patients in the first three categories compared to the last category (progressive disease). That is there is a measurable effect of treatment on the cancer – either improvement, or at least temporarily arresting or slowing the growth of the cancer.

For subjective response (relief of symptoms and/or improvement in well being or function) there is generally less agreement as to how to describe the outcomes. The term

‘clinical benefit’ is often used to describe the proportion of patients who improve by a predetermined amount. The focus of treatment goals is increasingly switching to this outcome, as being more patient centred

2

. Objective and subjective benefit are not always closely correlated.

One of the problems in assessing the true effect of treatment is the ability to measure it. If a drug kills a cancer cell, or stops it growing further it does not necessarily disappear, and it may appear incorrectly that there was no effect. Similarly a tumour consists of a very large number of cancer cells not all of which have the same potential to cause symptoms or spread. Therefore some of these cells may be killed, and the remaining cells have less potential to cause problems. Eventually bodily mechanisms may remove dead or dying cancer cells, but this takes time. Some tumours shrink much faster than others when treated. All of these considerations mean that less emphasis is being placed on objective response. This is discussed further under Disease Stabilisation.

Survival

Other terms used to describe outcomes include ‘progression-free survival’, or ‘diseasefree survival’ to indicate the amount of time from starting an intervention to the time when the tumour starts to grow again. This is an indication of the time gained by the intervention. For instance a patient with advanced disease may have a complete response after 6 months of treatment, and remain free of disease for a further six months (duration of response), and then have a recurrence of the cancer. The progression-free survival is a This only refers to cancer detectable by the best means available. It does not mean that there is no cancer, only time can tell that, and this is the reason why cancers can reappear after some time.

the time from the start of treatment to the end of the effect of treatment (twelve months in this case). Another patient may have a surgical removal of an early stage cancer, and have no evidence of disease for several years, and then develop a recurrence of their cancer five years after diagnosis. The disease-free survival is then described as being five years.

In contrast the terms ‘survival’ or ‘overall survival’ are used to describe the time till the death of the patient (from whatever cause). Survival information is often quoted as the

‘median’. For instance the median survival for advanced colorectal cancer has increased from 6 months to 21 months in the last few years. This means that now, at 21 months from diagnosis of advanced disease, 50% of patients have died and 50% are still alive.

‘Disease-specific survival’ is used to separate deaths from the cancer from deaths from other causes, although this distinction is not always easy to make with certainty.

Patients often find that a more helpful way of expressing this is the chance of still being alive at a point in time. For instance, the chances of still being alive two years after diagnosis of advanced colorectal cancer is approximately 40%.

3,4,5

Disease Stabilisation

Traditional teaching (dogma) in oncology has taught that only objective ‘responses’

(complete and partial response) matter, in terms of demonstrating that the intervention

‘worked’, because it was assumed that only objective response conferred any ‘benefit’, usually in terms of altered survival.

More careful research has demonstrated the fallacy of this.

6

For a patient whose tumour is growing, halting further growth for a time (delayed tumour progression) translates into a benefit in terms of the quality of life. Progressive tumour growth will usually be accompanied by an increase in symptoms, and a decrease in both functional status and quality of life.

7 For this to be a valid outcome, one must first establish that the patient’s current health status is considered worthwhile to them, in other words that they see it as worth maintaining, rather than simply lengthening their time in a state of health that has little value to them.

The second observation, as previously stated, is that objective response is not closely correlated with subjective response. In studies where tumour response and patients’ symptoms are carefully recorded, the subjective response is invariably higher than the objective response, because many patients in the stable disease group improve symptomatically and functionally.

An analysis of clinical trials in cancer which have reported both objective response

(including stabilisation) and subjective response demonstrates relatively high levels of subjective improvement, well in excess of objective responses, and including improvements in performance status. The implication is that many oncologists by over relying on objective responses underestimate the potential benefits of chemotherapy from a patient-centred

8

perspective.

For instance Ilson

9

found an objective response rate to chemotherapy in oesophageal cancer of 57%, with 40% stable, but a 90% rate of relief of dysphagia, while Andreyev

10 also found a 57% response rate but symptom relief ranging from improvement in weight

(100%) to dysphagia (71%).

Finally it has been demonstrated that at least some of the survival benefit from chemotherapy comes from the group with stable disease, not just those with an objective response.

For instance when docetaxel was compared to supportive (symptomatic) care alone as a second line intervention in lung cancer

11

, the objective response rate was quite low at around 6%, while 43% had stable disease (tumour control 49%). Yet survival was improved in the treated group overall compared to supportive care due to prolonged stabilisation of disease from the docetaxel. In colorectal cancer irinotecan was compared to supportive care alone as a second line therapy. Objective responses were seen in 14% but a further 44% had stabilisation (tumour control 58%).

12 Survival was improved overall.

13

35% of patients improved their performance status, and quality of life was improved.

provides another example, where response rates were 26%,

22% had stable disease (tumour control 48%), yet the vast majority of patients had improvements in symptoms and quality of life.

Curative Chemotherapy a

For reasons already mentioned this is not a particularly helpful term, since we are working on a continuum, and cure, even if we could define it, is often not a realistic goal in terms of probabilities. There is no substitute for the actual facts in providing information to patients and families. For instance, historically the cure rate for advanced colorectal (the large bowel – colon and rectum) cancer is 2-3%

14

, although thought to be improving with newer interventions. Chemotherapy is rarely curative in the common advanced cancers (breast, lung and bowel cancers).

Adjuvant Therapy b

The term ‘adjuvant’ (meaning ‘helping’) merely indicates that more than one form of therapy is being used in the overall treatment plan. Originally, one form of treatment

(usually surgery) was indicated as the ‘primary’ treatment, and others were considered to be assisting this, hence ‘adjuvant’. Typically this meant that surgery was ‘primary’ and other therapy, such as radiation or chemotherapy were ‘adjuvant’. Over time these distinctions have become blurred, and are perhaps better served by more precise descriptions of what is intended and how this is to be achieved.

While surgery may be used to establish a diagnosis, by exploration and/or a biopsy, many patients are diagnosed at a stage where surgical removal is not possible at least initially, or is not the highest priority. Because historically surgery was the only treatment for a DMAC 36 b DMAC 36

cancer, surgery has traditionally been considered the primary intervention in early cancer.

Even this is changing rapidly and it is not uncommon for surgery to now be performed after radiation, chemotherapy or both. For instance in cancer of the rectum it has been recently demonstrated that the best results are achieved when the usual order is reversed, and surgery is used last

15

. Other approaches include using surgery in the middle of a prolonged course of chemotherapy, after initial shrinkage of a tumour or tumours. All these changes have lead to some confusion in the terms used to describe interventions.

Neo-adjuvant Therapy a

This is a term best phased out. Originally it was meant to indicate that not only was a form of therapy ‘adjuvant’, but that it was given before the primary therapy (generally surgery), as opposed to after . A more precise description is preferred, indicating the order in which different interventions are being offered, e.g. preoperative radiation with chemotherapy.

Induction Chemotherapy

This term refers to the sequencing of chemotherapy in relation to other treatment strategies, indicating that the initial therapy is provided by chemotherapy, followed by other approaches. For instance in locally advanced rectal cancer, initial therapy is often with chemotherapy, followed by combined chemotherapy with radiation, and then surgery. Similar approaches have been taken in oesophageal and anal cancer. This can provide rapid relief of symptoms while other strategies are being planned.

16

Palliative Chemotherapy b

Literally, this means relieving symptoms

17

. For the reasons already indicated under the heading Curative Chemotherapy, this is a term that has also lost its meaning, and experts argue should be dropped, in favour of defining the specific goals of therapy for the individual patient

18,19

, in the interests of improving communication and avoidance of confusing patients.

20

Unfortunately, careful questioning of patients shows that confusion about goals is common.

21 Thus ‘curative’ and ‘palliative’ chemotherapy are not mutually exclusive alternatives.

Chemotherapy has the potential to achieve a number of outcomes, spelt out in detail below, of which improvement of well-being, or palliation is but one.

Nevertheless a useful distinction can be made between two scenarios at each end of a spectrum, that of early disease and that of advanced disease. In early disease the chance of cure may be relatively high, and the extent of disease relatively low or undetectable. In this case patients need to consider the probability of harm in relation to minimal immediate benefit, but the possibility of ultimate benefit (prolonged remission or cure).

In more advanced disease, the chance of cure is low, and the extent of disease and hence its manifestations, greater. In this case the patient needs to consider the possibility of harm in relation to both immediate goals (improvement of disease) and longer term goals a DMAC 37 b DMAC 37

(the prolongation of the quality or quantity of life). Nevertheless it is worth keeping in mind, as has already been noted, an increasing emphasis on the goals of improving tumour related symptoms as opposed to simply measuring the patient’s tumour. This is in keeping with the concept that ‘palliative’ care is no longer something that is left to the last stages of a patient’s life, but is an inherent component of all aspects of a patient’s care throughout its course.

22

Setting Goals

The traditional duties of a physician from mediaeval or even earlier times have been enshrined in the epithet;

"To cure sometimes, to relieve often, to comfort always a

-- this is our work. This is the first and great commandment. And the second is like unto it - Thou shalt treat thy patient as thou wouldst thyself be treated."

23

Thus comfort and relief (support and palliation) are the prime immediate objectives of any care plan.

Traditionally palliation has been achieved in two complementary ways, the use of interventions designed primarily to relieve symptoms (e.g. pain, nausea), and those interventions targeted at the underlying disease with the intent of relieving symptoms caused by the disease. These must always be primary considerations.

We might refine the ‘cure sometimes’ duty to extend to those goals which alter the natural history of the disease. To that extent it is important to consider life as having two dimensions, quantity and quality. Altering the natural history may change survival, but it also changes the time spent in different phases of the disease. The quality of life

24

is correlated with, amongst other things, the extent of the cancer. Therefore the longer one can restrain the cancer from growing, the more time the patient spends in better states of health. This is the rationale for including ‘progression-free survival’ as an outcome to be considered in setting goals.

Therefore, to recapitulate, the outcomes of interest to be considered in setting goals include, in chronological order, relief of symptoms, inducing a regression of the disease extent, delaying further growth of the cancer, extending the survival time and improving the chance of cure.

Outlining possible outcomes and their likely probability is but one key step in establishing and providing the information for informed decision making. The other two being eliciting the values and preferences of the patient themselves (which is discussed more extensively elsewhere in Clinical Judgement: Decision making in oncology: Values and preferences ), and the potential for harm.

Strictly speaking quality of life is the balance achieved in the interplay between the effects of the disease process on one hand, and that of unwanted effects of any a Guérir quelquefois, Soulager souvent, Consoler toujours

interventions on the other. An important consideration in understanding this interplay, is that changes in disease status are relatively sustained, while those of treatment tend to be transitory.

Ошибка! Закладка не определена.

Goals and Judgements in Early Disease

Theoretically the treatment of early disease in the absence of measurable disease, to prevent recurrence is ‘overtreating’ some people who might never have disease recurrence, unfortunately there is no way to accurately predict which patients will have a recurrence of their disease and which will not. However some degree of estimation of the probability can be obtained from a variety of information sources including the characteristics of the patient, and of the cancer.

When provided with the statistics regarding treatment of early disease, most, but not all patients will judge the potential gain worthwhile. These statistics include the potential benefit and the potential for harm. Not only has the intensity of the interventions offered in this context continued to escalate, but the toxicities encountered in clinical practice are not insignificant. For instance postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with fluorouracil in early large bowel cancer results in hospitalisation rates (which might be equated to severe to life threatening toxicity) from 5-30%

25

and were no different in early than in advanced disease

26,27

.

Psychosocial morbidity (patient distress) are sometimes greater in the context of early disease, since there is no tangible trade off in terms of evidence of disease regression

(where the disease is being prevented from reappearing), compared to patients with advanced disease. The potential gains (prolonged remission, increased survival) remain theoretical in the short term when patients are actually undergoing their therapy.

Goals and Judgements in Advanced Disease

Decision making in advanced disease is by necessity more complex than in early disease because of the multiplicity of potential endpoints. On the other hand improvements in well-being may be more immediate providing an important trade off against the side effects of therapy, and hence the patient’s perceived quality of life.

Thus, when Priestman and colleagues 28 compared hormonal therapy with cytotoxic chemotherapy in advanced breast cancer, they observed that despite more side effects from cytotoxic chemotherapy, the quality of life was actually better because disease regression occurred in much higher percentage (49% v 21%) than with hormones.

Similarly in gastrointestinal cancer Gough

29

first described how patients’ quality of life was improved with chemotherapy despite low objective response rates.

Another example is provided by the Nordic Gastrointestinal Tumour Group

30,31

, comparing combination chemotherapy with a single drug. Although there was more toxicity with the combination, patients reported better quality of life because there was more improvement in this group.

Dr Michael Goodyear

Department of Medicine

Dalhousie University

Halifax, Nova Scotia

August 2006

References Cited

1 Marchione M. 'Cure' a 4-Letter Word for Cancer Doctors. Associated Press September 20 2004.

2 Jager E, Bernard H, Knuth A. Palliative treatment for advanced gastrointestinal cancer: is response a suitable end-point? Cancer Treat Rev. 1996 Jan;22 Suppl A:113-5.

3 Goldberg R, Sargent D, Morton R et al. A randomized controlled trial of fluorouracil plus leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin combinations in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer.

J Clin Oncol. 22(1): 1-8, 2004.

4 Tournigand C, Andrè T, Achille E et al. FOLFIRI followed by FOLFOX6 or the reverse sequence in advanced colorectal cancer: A randomized ERCOR study. J Clin Oncol 22(2) 229-37, 2004.

5 Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer NEJM 350(23): 2335-42, 2004

6 Petrou S, Campbell N. Stabilisation on colorectal cancer. Int J Palliative Nursing 3(5): 275-280, 1997.

7 Allen M, Cunningham D, Schmitt C. Randomised trial of irinotecan plus supportive care versus supportive care alone after fluorouracil failure for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1998

Oct 31;352(9138):1413-8.

8 Laine C, Davidoff F. Patient-centred medicine. A professional evolution JAMA 275: 152-6, 1996

9 Ilson DH, Saltz L, Enzinger P, Huang Y, Kornblith A, Gollub M, O'Reilly E, Schwartz G, DeGroff J,

Gonzalez G, Kelsen DP. Phase II trial of weekly irinotecan plus cisplatin in advanced esophageal cancer. J

Clin Oncol. 1999 Oct;17(10):3270-5.

10

Andreyev HJ, Norman AR, Cunningham D, Padhani AR, Hill AS, Ross PJ, Webb A. Squamous oesophageal cancer can be downstaged using protracted venous infusion of 5-fluorouracil with epirubicin and cisplatin (ECF). Eur J Cancer. 1995 Dec;31A(13-14):2209-14.

11 Shepherd FA, Dancey J, Ramlau R, Mattson K, Gralla R, O'Rourke M, Levitan N, Gressot L, Vincent M,

Burkes R, Coughlin S, Kim Y, Berille J. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J

Clin Oncol. 2000 May;18(10):2095-103.

12 Cunningham D et al.. Open-label multicentre phase II study to confirm efficacy and safety of irintotecan-

HCL (CPT-11) in metastatic 5-FU resistant colorectal cancer (CRC). Brit J Can 74 (Sup XXVIII): Abstr

034

13 Cunningham D, Pyrhonen S, James RD, Punt CJ, Hickish TF, Heikkila R, Johannesen TB, Starkhammar

H, Topham CA, Awad L, Jacques C, Herait P. Randomised trial of irinotecan plus supportive care versus supportive care alone after fluorouracil failure for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1998

Oct 31;352(9138):1413-8.

14 Perez N, Tournigand C, Mabro M et al. Survie à long terme des cancers colorectaux métastatique sous chimioth’erapie par 5-fluoro-uracile [Long term survival in metastatic colorectal cancer treated with leucovorin and 5-fluoro-uracil chemotherapy] Rev Mèd Int 25: 124-8, 2004

15 Roh M, Colangelo S, Wieand M et al. Response to preoperative multimodality therapy predicts survival in patients with carcinoma of the rectum. Proc ASCO 2004: 3505

16

Chau I, Brown G, Cunningham D, Tait D, Wotherspoon A, Norman AR, Tebbutt N, Hill M, Ross PJ,

Massey A, Oates J. Neoadjuvant capecitabine and oxaliplatin followed by synchronous chemoradiation and total mesorectal excision in magnetic resonance imaging-defined poor-risk rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol.

2006 Feb 1;24(4):668-74.

17 Rubens RD, Towlson KE, Ramirez AJ, Coltart S, Slevin ML, Terrell C, Timothy AR. Appropriate chemotherapy for palliating advanced cancer. BMJ. 1992 Jan 4;304(6818):35-40.

18 Jefford M, Zalcberg J. Palliative chemotherapy: a clinical oxymoron. Lancet 362: 1082, 2003.

19 van Kleffens T, Van Baarsen B, Hoekman K, Van Leeuwen E. Clarifying the term 'palliative' in clinical oncology. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2004 Jul;13(3):263-71.

20 The AM, Hak T, Koeter G, van der Wal G. Collusion in doctor-patient communication about imminent death: an ethnographic study. West J Med. 2001 Apr;174(4):247-53.

21 Doyle C, Crump M, Pintilie M, Oza AM. Does palliative chemotherapy palliate? Evaluation of expectations, outcomes, and costs in women receiving chemotherapy for advanced ovarian cancer. J Clin

Oncol. 2001 Mar 1;19(5):1266-74.

22 Sepulveda C, Marlin A, Yoshida T, Ullrich A. Palliative Care: the World Health Organization's global perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002 Aug;24(2):91-6.

23 Anonymous. Cited in Johns Hopkins Medical School handbook for housestaff. http://dcs.jhmi.edu/cvo/PostDoctoralHandbook_2006.pdf

24 Goodyear M, Fraumeni M. Incorporating quality of life assessment into clinical cancer trials. In: Spilker

B (Ed.) Quality of Life and Pharmacoeconomics in Clinical Trials. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia 1996, pp 1003-1013.

25 Delea T, Vera-Llonch M, Edelsberg J et al. The incidence and cost of hospitalizsation for 5-FU toxicity among Medicare beneficiaries with metastatic colorectal cancer. Value in Health 5(1): 35-43, 2002

26 Tomiak A, Vincent M, Kocha W et al. Standard dose (Mayo regimen) 5-fluorouracil and low dose folinic acid: Prohibitive toxicity? Am J Clin Oncol 23(1): 94-98, 2000

27 Tsalic M, Bar-Sela G, Beny A, et al. Severe toxicity related to the 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin combination

(The Mayo Clinic regimen). Am J Clin Oncol 26(1): 103-106, 2003

28 Priestman T, Baum M, Jones V, Forbes J. Comparative trial of endocrine versus cytotoxic treatment in advanced breast cancer. Br Med J. 1977 May 14;1(6071):1248-50.

29 Gough IR, Furnival CM, Burnett W. Patient attitudes to chemotherapy for advanced gastro-intestinal cancer. Clin Oncol. 1981 Mar;7(1):5-11.

30 Nordic Gastrointestinal Tumour Adjuvant Therapy Group. Superiority of sequential methotrexate, fluorouracil, and leucovorin to fluorouracil alone in advanced symptomatic colorectal carcinoma: A randomised trial J Clin Oncol 7(10): 1437-1446, 1989

31 Glimelius B, Hoffman K, Olafsdottir M, Pahlman L, Per-Olow S, Wennberg A. Quality of life during cytostatic therapy for advanced symptomatic colorectal carcinoma: A randomised comparison of two regimens Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol 25(5): 829-835, 1989