`Why are we here - Fiery Spirits Community of Practice

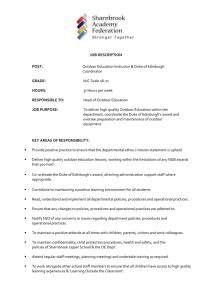

advertisement

‘Why are we here?’ Taking ‘place’ into account in UK outdoor environmental education Sam Harrison PhD Candidate, Moray House School of Education, The University of Edinburgh Abstract: ‘Place’ is an under-researched and poorly documented element of United Kingdom outdoor environmental education. In the USA ‘place-based education’ continues to grow, and Australian outdoor education journals show considerable attention to ‘place.’ Yet UK outdoor environmental educators and researchers seem to have neglected this area despite Nicol and Higgins’ call for increased attention to this element of education in the outdoors, (Nicol & Higgins, 1998). This paper examines the considerable and diverse literature on ‘place’ from a variety of disciplines, examining the implications both for the UK and international environmental education literature. My own experiences as a practitioner searching for ways to bring out the rich nature of the venues I use anchor more theoretical considerations. Drawing on Action Research, a tentative ontology and epistemology are put forward which raise a set of pressing questions. Welcome to Staoineag Clouds of midges. Literally millions. They have formed a living ball on my rucksack strap outside the tent, and the grass around it is brown and moving with insects. The other instructor and I agree that in our (quite extensive) experience working in the Scottish hills, this is the worst that we have seen. That evening, listening to the screams and giggles of the group in their tents, we stop and I wonder why we are here at Staoineag. Why here, in this place? The underlying assumption of the week-long programme I had been asked to co-deliver is that ‘wilderness,’ or at least a remote area of wild land, would provide the location (and content) for an experience which delves into questions of personal relationship with nature, and commitment to environmental activism. There are many points on which to debate this assumption: the question of ‘wilderness,’ (Nash, 1982; Turner, 1995), the validity of a ‘significant life experience’ approach (Payne, 1999), or how it could be said that this week ‘works,’ (Allison & Pomeroy, 2000). However the question I want to ask is ‘why were we there, in that particular place?’ At Staoineag, this query had its immediate forms – ‘what am I doing here in this midge-infested moor?’ and ‘how do I / the group cope with this?’ Furthermore, it took the form of more general questions: ‘what have the Scottish hills got to do with environmental / cultural issues such as climate change, recycling, sustainable futures?’ Equally there were grounded forms of this question such as ‘what is there about this particular tree that we might learn from?’ ‘what is the nature of the relationship between ourselves and this place?’ and ‘what can being here, at Staoineag Bothy, as opposed to anywhere else, contribute to the group’s learning?’ That these questions resonate beyond the facilitation of this particular project can be illustrated by critically examining two responses to these enquiries about Staoineag, from the perspectives of Deep Ecology and Eco-psychology. I have recently worked on several projects based on these understandings, which might indicate a growing awareness of such views in the United Kingdom. These schools of thought also provided some of the unwritten basis for the project in question. Simply put, an argument from Deep Ecology might state that the group are in the process of developing a sense of ecological self, (Bodian, 1995; Fox, 1995b; Sessions, 1995) which will move them towards a different, and perhaps more sustainable, way of being. In fact, as Arne Naess, ‘father’ of Deep Ecology, tells Bodian, the process of ‘identification’ moves from local places towards identifying with the universe, (ibid, p26-7) thus seeming to become more abstract and less ‘placed.’ Fox discusses this lack of concreteness, but fails to grasp the epistemic hole in which this puts Deep Ecology, (Fox, 1995a). While a global sense of ecology might be congruent with the aims of the project, it doesn’t answer the question of how the process might happen; why we might be at a bothy in the middle of the West Highlands of Scotland rather than anywhere else. If Deep Ecology can’t help us answer the question of ‘place’ educationally, then perhaps Eco-psychology, being closely related (Bragg, 1996), and arguably more practical in focus can achieve this. An Eco-psychologist might argue that the group are forming healthy relationships with the environment around Staoineag, providing a chance to access deep feelings about ourselves and this place, and understand its significance in their lives, (there are many examples of this practice (Birrell, 2001; Horesh, 1998; Rogers, 2000)). And yet, while these authors maintain the Eco-psychological idea of healthy relationships between people and places (Conn, 1995, p. 163), what relationship have ‘my’ group really got with this bothy? The group will be at this place for two days and then, most likely, will never return. We might compare the relationship with this place to a relationship with a human. While we all might recollect meeting someone very briefly who had an impact on us, is this a metaphoric chance that we want to build an educational project on? Martin and Thomas (2000) suggest that if we use this metaphor, time and effort need to be spent to develop a sense of connectedness, and that relationships need to be allowed to progress from acquaintance to intimacy to result in care for places (Martin & Thomas, 2000). Furthermore, Martin’s research with some of these approaches, provided testimony from one student who, being asked to feel ‘at one’ with nature before getting to know it, compared this to a one-night stand, (Martin, 2004, p. 25). The questions of time and breadth of relationship with place are not dealt with in the majority of Eco-psychological literature. This discipline, largely, can be seen to imply a relationship with ‘natural’ places based on very brief, possibly intense feelings, without any context or other forms of knowledge.1 Thomashow relates his experience of Eco-psychological approaches to places which are limited to subjective, or emotional understandings: …as I observe and participate in a sampling of these gatherings, I notice the glaring absence of any attention devoted to basic ecology and natural history. People who are delighted to open their sensory awareness to a beautiful tree or landscape often have an extremely limited understanding of the natural history of the site, thus totally lacking an ecological context for what it is they are looking at. The risk here is that their impressions of the landscape and ecosystem are projections and fantasies, filled with whatever idiosyncratic or group constructed unconscious contents are at their disposal. This may be great for cultivating the spirit of imagination or opening the gates to deep personal issues, but it is ultimately anthropocentric, neglecting the rich natural history tapestry that nourished a deep sense of place, (Thomashow, 1998, p. 284). Deep Ecology and Eco-psychology have a lot to offer outdoor environmental education, but the brief discussion above shows that they have yet to develop meaningful responses to the question ‘why, or what about, here?’ More importantly they draw out the discussion of one example (Staoineag bothy), to imply wider questions. These queries involve epistemology: what ways might we come to know places – how much time would we spend, and with what approaches? and ontology: what is the nature of place we are talking about; a physical location, a set of feelings about somewhere? As should be clear from the foregoing discussion, these debates are not purely conceptual but have a strong impact on practice and practitioners. A diverse literature These questions aren’t without precedent, considerable time has been spent theorizing, and increasingly, researching with participants, the role of ‘place’ in outdoor environmental education. This writing can be largely divided into two areas: American ‘place-based education,’ (Bishop, 2004; Gruenewald & Smith, 2008; Knapp, 2005; Smith, 2002; Sobel, 2004; Woodhouse & Knapp, 2001), which is focused on classroom teachers embracing the local community and environment as part of the learning context. The second area consists of considerable Australian and Canadian writing on ‘place’ in outdoor environmental education (Brookes, 1998, 2002a, 2002b; Curthoys, 2007; Gough, 2008; Henderson, 2001; Preston, 2004; Preston & Griffiths, 2004; Stewart, 2003, 2006a, 2006b, 2008). The focus of this writing is on outdoor educators and the provision of stand-alone environmental education programmes, thus dealing with the places which are visited as part of these programmes, but are not necessarily lived in by participants or facilitator. What is striking about the North American and Australian writing is that largely they do not refer to each other: could useful insights could be gained from 1 An exception to this is put forward by the Eco-psychological practice of Shapiro, who suggests long-term restoration projects as a method of promoting personal and environmental well-being, (Shapiro, 1995). exchange, and what might such far-off places mean to the UK? This raises a further question about place: does a place-based practice have to be narrowly delimited? Can we learn anything from ideas originating in another place? This debate about the size and interconnection of places will be taken up later in this paper, however for the moment, what is clear from the above writing is that, while it often deals in specifics from other places, for example the cultural history of Borhoneyghurk Common in Australia (Preston, 2004), it could inspire general principles and the development of specific practices in the UK. While outdoor environmental educators would be inadvisable to wholesale import examples of place-based practice (in the same way as the Australian writers critique uncritical adoption of UK and American practices e.g. (Lugg, 2004)), there is a pronounced lack of contemporary UK contribution to this exciting and current debate. Ten years ago, with regards to ‘place’ in outdoor environmental education, Nicols and Higgins stated that “the outdoor literature in the United Kingdom is conspicuous by the absence of any treatment of this relationship,” (Nicol & Higgins, 1998, p. 53). Very little has changed since then; the two UK papers which deal with this (Nicol, 2003b) and (White, 1998) are very hard to access, and rarely cited. Some classroom-based approaches in the UK are taking up programmes which are similar to ‘place-based education,’ and there are a small number of projects which aren’t school based,2 with more possibly more out there. A common feature of the arguments used to justify these UK examples is a focus on the benefits of outdoor education in general (such as health, personal and social development and attainment), rather than any specific justification of a place-based approach (see the websites cited above for examples). Thus they leave the fundamental question of this paper, ‘why here?’ unanswered. Despite engagement by some schools, the lack of recent educational literature on ‘place’ shows that outdoor environmental education providers and researchers have not taken up the challenges of this debate. Arguments for considering ‘place’ in UK outdoor environmental education and an ontological and epistemological framework for such an effort are the focus of the paper. Given the strong dialogue on place in outdoor environmental education in North America and Australia, it is surprising that there is little research or widespread practical engagement in educational projects apparent within the UK. However, it is not within the scope of this paper to investigate the reasons behind this apparent neglect. The purpose of this paper is to draw out the salient elements of the wider non-educational literature on place, relating 2 This includes the authors work (www.openground.eu), Dr. Simon Beames’ development of and research on Outdoor Journeys (www.outdoorjourneys.org), Linda-Jane Simpson’s work on drama in teacher education at Moray House, the University of Edinburgh (research publication forthcoming). Forest Schools (www.foresteducation.org) and ‘grounds for learning’ (www.gflscotland.org.uk) also bring questions of locality and time spent at one venue into school based projects. Forestry Commission Scotland have just undertaken a feasibility study on using the Scandinavian model of ‘forest kindergartens’ in a Scottish context, this might touch on issues of ‘place.’ this to the UK and beyond. More concretely, I will use this as a method of critically examining my practice as an outdoor educator. An ontology and epistemology of place I am walking with a group of nine and ten year-olds down to Clach Thoull (Scottish Gaelic: ‘the holed stone’). The tide races through the Lynn of Lorn between Appin and the isle of Lismore (the ‘big garden’). In smaller caves along the route, limestone, which gives its fertility to Lismore, forms small stalagmites. The tide used to race through the arch of Clach Thoull when the sea level was some 14m higher: now the rock stands way above the tide-line. One of the boys lives just five minutes walk from here, and he leads us round the path pointing out some of the things he knows. Other members of the group ask questions about the things around them, and I bring questions of my own. This ‘Project about my place’ has fortnightly outings to the areas around the participants’ homes in North Argyll, Scotland. The starting point for this project is a sense that local places are important, worthy of consideration, rich in detail and an integral part of who we are. These ideas have strong backing in an extensive multi-disciplinary literature on place, spanning geography (Mackenzie, 2006b; Massey, 2005; Paasi, 2004; Tuan, 1974, 1977), anthropology (Feld & Basso, 1996), environmental psychology (Hernandez, Hidalgo, Salazar-Laplace, & Hess, 2007; Korpela & Hartig, 1996; Krupat, 1983; Rogan, O'Connor, & Horwitz, 2005; Sarbin, 1983; Schroeder, 2007) and philosophical enquiry (Casey, 1993, 1997; Macauley, 2006; Malpas, 1999; Seamon & Mugerauer, 1985; Szerszynski, 2006; Young, 2002).3 Some of this broad and well-developed academic discourse is brought into North American and Australian discussions of place in education. However, much of the modern geographical theorizing of place, the thought of Doreen Massey for example, and the vast body of environmental psychology research into place-identity and attachment is absent. Reviewing the ways in which this theory and research can inform the project sketched above, will reveal both a philosophical underpinning to a UK practice of place and also some areas in which the current international literature on place in outdoor environmental education could develop. In the field of environmental psychology, considerable quantitative research has been conducted into measuring ‘sense of place,’ ‘place-identity,’ and ‘place attachment.’ This research provides measures of these indicators and also evidence of ways in which people and places form complex and dynamic relationships which can prompt ongoing learning and constitute a locus for responsible action, (Rogan et al., 2005). Measurement of possible increases in place attachment of my group walking and learning around their homes every fortnight is not a possibility, due to time and resources. If it were possible it might perhaps be advantageous, the ‘hard’ evidence could be used to convince funders or policy makers of the necessity of such a project, or of objective gains in these categories. 3 Bioregionalism also provides political dimensions to concerns of place, (Jackson, 1994; Sale, 1985) but are more peripheral to this discussion. More importantly, the environmental psychology research tackles questions relating to what a certain level of ‘sense of place’ or ‘place attachment’ might lead to. Researchers consider questions such as ‘what difference in approach to place do ‘natives’ and ‘non-natives’ have?’ (Hernandez et al., 2007) and ‘what is the ‘place’ we are talking about?’ (Krupat, 1983). These have direct correlations to facilitation: ‘in what ways does the fact that I and most of my participants who were not born and brought up here affect our learning about this place?’ and ‘by ‘place’ do I mean ‘Western Scotland,’ ‘Argyll’ (the county), Appin (the home area of some of the participants) or Clach Thoull (a physical area of say 50 square metres)? Some environmental psychologists question the limits of positivistic research, pointing to the ways in which place is a dynamic interaction between people and locations, thus requiring phenomenological research approaches (Sarbin, 1983; Schroeder, 2007).4 These questions also form a strong element of geographical writing on ‘place.’ Fiona Mackenzie has spent considerable time recording testimony from community land buy-outs in Scotland (Mackenzie, 2002, 2004, 2006a, 2006b). She theorizes place as a process through which communities negotiate their sense of themselves and the politics of the land. Significantly she highlights the community practices which break down the ‘native versus incomer’ barriers (a problem which lurks at the edge of any discussion of place – see for example Schama’s analysis of the use of the German forest in the rise of Nazism (Schama, 1995)). Also, Mackenzie questions the role of ‘wilderness’ and conservation designations in accurately representing the land and communities which live there. She describes the ways in which communities such as North Harris, in the Western Isles, have resisted these ways of seeing place, asserting the continuing human and cultural presence in these areas, (Mackenzie, 2006b, p. 591). Again this speaks to the practical questions of how to run the project I have described: finding ways in which both ‘incomer’ and ‘native’ can speak for, and deepen their relationships with, the places where they stay, whilst acknowledging the different understandings they may bring. These questions may inspire a renewed focus on the rich cultural as well as environmental heritage of Scottish land. The book ‘On the other side of sorrow,’ by historian James Hunter, describes the ways in which highland and environmentalist conceptions of the Scottish landscape developed and, more recently, have clashed (Hunter, 1995). Hunter points out the roots of viewpoints on the Highlands which see a beautiful landscape and yet fail to acknowledge the, often tragic, human history. This is a viewpoint which is prevalent in outdoor environmental education in the UK, as White’s research shows (White, 1998). White contrasted the views of those who lived and worked on the lands with outdoor educators, calling for them to become much more aware of the culture in the landscape (White, 1998, p. 2). 4 This implies that a critical educational process could perhaps be a suitable research method even for an environmental psychologist. Whilst recognition of the history of a place is important, there is a need also to bring out the distinctly modern interconnection between different people and places. We are no longer in a time, if we ever were, where things, people and ideas stay in one place for a long time. Doreen Massey deeply analyses this, looking at the ways in which modern places are interconnected and constantly evolving, or co-evolving (Massey, 2005). This speaks to the need for a pedagogical approach to place-based learning capable of drawing in connections from other places,5 and acknowledging the agency of the group in the ongoing story of the places they are in. In the ‘Project about my place’ we scale up and down between places constantly – in each session we visit a different home place of a participant, but are still geographically and culturally within a homogenous larger place (North Argyll); geologically the horizon extends again. This consideration has broader consequences – what of getting in a mini-bus and driving to a venue in the Scottish Highlands from a UK city or other rural location, (a prevalent practice for outdoor environmental education)? The idea of being in the same place as home is stretched to breaking point, 6 but what about the quality of ‘away’ places? This theme is taken up by some of the philosophical writing on ‘place:’ Young points out the contradiction between the Heideggerian idea of dwelling in, and authentically speaking for, our home places (Heidegger, 1971) with wanting to speak for endangered and threatened places around the globe: places where we are not ‘at home,’ (Young, 2002). Young concludes that to avoid the abstraction of talking about places far away, we need to experience and creatively ‘open ourselves up’ to them. This might imply that it is still worth seeing the typical UK environmental education venue (a highland glen, loch or hill) as a place in itself.7 This is a theme also investigated by Szerszynski. He draws on evidence from Northern England to contrast the ‘aesthetic’ approach to place of newly settled people in a town to the ‘relationship’ orientation of people who having been living there all their life (Szerszynski, 2006). Could this contrast be brought out educationally in the contrast between ‘home’ place and ‘away’ place? Other philosophical work lends weight to an ontology of place as ‘co-created:’ the environment both shaping and being shaped by human and vice versa (Kidner, 2001; Lukenchuk, 2006; Malpas, 1999; Merleau-Ponty, 1968). 5 Only a very narrow reading of place-based education would have it solely about that single place – wider connections and possible transferability have to be important: “if students are allowed to learn how to care about a place and to care for it, they are more likely to consider living there and helping to solve its problems. A pride of place will also give them the necessary skills to live well in any community. Place-based learning, wherever that place is, teaches a sense of community and gives students a model for living well anywhere,” (Bishop, 2004). 6 Though we might have bio-physical connections to that place through food, waste energy cycles, how deep and educational are our emotive and lived connections to such a far away place? 7 US writing on place-based education is orientated around the school and the community, so it does not broach the questions of ‘away’ and ‘home’ places which are raised in the outdoor environmental education model. This raises questions of the validity of experiences in natural environments which might be found relatively far away from home are valuable. Practice adds complexity to this concept – there is no way in which humans have shaped the physical structure of Clach Thoull, yet the rock provides opportunity to look at the way in which people attribute meaning and names to things, and the ways in which the landscape formed and thus determined some of the cultural elements of the area (e.g. settlement on fertile raised beaches caused by sea-level change, or the effects of incipient man-made changes in sea-level). This ontological position raises a question which recurs throughout environmental debates – is the environment a human construct or a scientifically measurable entity, or both? (see for example (Gruenewald, 2003)). An ontology of place which meets this concern, describing the dynamic interrelationship of subject and object, and a middle ground between positivism and post-modern ontologies, is put forward in Action Research as a ‘participatory world-view:’ A participatory view competes with both the positivism of modern times and with the deconstructive postmodern alternative... However, we can also say that it also draws on and integrates both paradigms: it follows positivism in arguing that there is a ‘real’ reality, a primeval givenness of being (of which we partake); and draws on the constructionist perspective in acknowledging that as soon as we attempt to articulate this we enter a world of human language and cultural expression. Any account of the given cosmos in the spoken or written word is culturally framed, yet if we approach our inquiry with appropriate critical skills and discipline, our account may provide some perspective on what is universal, and on the knowledge creating process which frames this account, (Reason & Bradbury, 1999, p. 11). This ontology allows space for ecological and cultural understandings of place, bringing together the emotional and scientific as already mentioned in the above critique of eco-psychology (Thomashow, 1998). The above implies an epistemology of place which embraces multiple ways of knowing: scientific, cultural, emotional, but requires a practical engagement over time with a place.8 Also implied here is a complexity of relationship which involves places changed by the ongoing lives of people and people changed by the ongoing lives of places. Action Research describes an epistemology which attempts to account for such richness and dynamism. Reason’s ‘extended’ epistemology captures a variety of different ways of knowing: ‘experiential,’ ‘presentational,’ ‘propositional’ and ‘practical,’ (Reason, 1998; Reason & Heron, 2008). This epistemology allows differentiation between direct personal experience of things, representations of these experiences, various bodies of theoretical knowledge we might bring to bare, and practical understanding. These are not isolated elements: for example, this extended epistemology might account for direct experience of Clach Thoull (experiential knowing), and a variety of 8 As Dr. Robbie Nicol points out, this question of action ‘for’ place is often thrown into stark contrast by crisis, such as building projects or windfarm applications (personal communication). forms of expression of the arch – drawings, discussions, memories (presentational knowing). Different conceptual developments of that experience are possible: an understanding of glacial and post-glacial sea levels, or of Gaelic place-names (propositional knowing). It might inspire action grounded in this understanding: a further interest in geology, taking someone else to see the rock (practical knowing). Nicol has already applied this epistemological framework to outdoor environmental education theory and practice (Nicol, 2003a). However the particular applicability to how we understand places remained implicit. Returning to the international literature on place, several things are clear: a UK practice of place-based outdoor environmental education is implied by a consideration of the wider literature on place independently of North American or Australian educational writing. Furthermore, the projects described by various educators in these places (Bishop, 2004; Brookes, 2002a; Preston, 2004; Smith, 2002; Stewart, 2006b) are supported, often more deeply than the authors state in own their writing, by the above considerations. To various degrees, they all fit a similar model consisting of going outdoors into a locality (often perceived as not especially ‘wild’), spending considerable (in educational terms) periods of time in places, finding different ways of understanding and expressing these experiences, accessing local knowledge, contributing to the community. All these projects, overtly or by implication, employ an Action Research methodology (for example Gruenewald states that Action Research is fundamental to place-based education (Gruenewald, 2003)). We can see how this element of practice is strongly implied by the underlying epistemology and ontology of place described here. This is not to argue that North American and Australian place-based practice is homogenous in any simplistic way, but that a deeper analysis of the conceptual underpinnings of this practice reveals similar concerns which could be further developed. These key considerations are: ‘what and where is the place we are talking about? ‘how do we learn about this place?’9 The above discussion adds a depth of critique to current debate: for example - is there more to ‘place’ than simply the location of experience (as Gruenewald argues (2003)), and is the word ‘place’ itself placeless, inherently generalised and abstracted from locations such as Clach Thoull and Appin (Gough, 2008)? Possible directions for the UK There is an obvious need for research on these topics. Personal experiences as a facilitator don’t provide enough evidence to add further to the practical elements of the debate, and there are some complex theoretical questions which could be delved into. Having gained a clearer conceptual understanding and looked at other well researched (albeit Australian) examples (e.g. (Preston, 2004; Preston & Griffiths, 2004), there is an outline 9 Some of the literature asks these questions, for example (Stewart, 2003), but often remains unaware of the level of interaction with these debates in wider disciplines. of a project which might begin to provide research data relevant to these discussions:10 a series of visits to the same place a diverse, and increasingly participant directed, experiential approach to understanding the place – through ecology, cultural history, geology, geography, place-names, interactions with local community, work projects a variety of ways of recording and linking these experiences to wider issues – discussions, journaling, artwork, building up a body of work which is contributed to by participants and community members an approach which includes different ways of knowing the place: emotionally, scientifically, as a visitor, from the testimony of people who work there etc. Having referenced place-based outdoor environmental education practice which seems to have developed congruently to, but sometimes with very little concern for, the philosophical questions investigated here, the query arises ‘what is the point of all this theory?’ For educators who do research and vice versa, this prompts further questions: having developed an ontology and epistemology of place, what kind of research would have an impact on that theory, rather than just being inspired by it? Would the idea of praxis, as the critical interaction of theory and practice, (Collins, 2004; Cotton & Griffiths, 2007; Meyers, 2006), be realistic for a practitioner, and contribute to the above model? What remains is a challenging and engaging process of placing ourselves as practitioners in the UK. We might ask how far we travel to our venues – do we have to go ‘away?’ And wonder how much we know about the venues we use, whether it is useful, or desirable, to be an ‘expert’ in certain places. We might look at the rich character of the places we work in and ask how our groups might have a more significant contribution to them, or what different cultural ways of knowing landscape we have within the UK. Another important concern turns around how might we research this: Action Research methodologies are an obvious candidate, but what other approaches might work? What sort of evidence might justify a place-based learning project, would it solely be provided by humans or might the environment provide data also? What academic writing styles and logic might reflect this knowledge of place? Furthermore, I have deliberately not put place-based outdoor learning into a wider context: the impacts on sustainability education, mental and physical well-being, personal and social education in the outdoors, community development and more are beyond the scope of this paper and my research. However these links present an opportunity to connect with wider currents in education, raising even more complex questions. For example: ‘what has ‘place’ to do with sustainability?’ ‘how might we know we have had an effect on personal or ecological sustainability in certain places,’ and ‘do we want to 10 A pilot study, followed by a full project, along these lines is the next stage of my PhD research aim at such change?’ Here is a rich vein of research and practice yet to be tapped within UK outdoor environmental education. References Allison, P., & Pomeroy, E. (2000). How shall we 'know?': epistemological concerns in research in experiential education. The Journal of Experiential Education, 23(2), 91 - 98. Birrell, C. (2001). A deepening relationship with place. Australian Journal of Outdoor Education, 6(1), 25 - 30. Bishop, S. (2004). The power of place. The English Journal, 93(6), 65 - 69. Bodian, S. (1995). Simple in means, rich in ends: an interview with Arne Naess. In G. Sessions (Ed.), Deep Ecology for the 21st century: readings on the philosophy and practice of the new environmentalism (pp. 26 - 37). Boston: Shambhala. Bragg, E. A. (1996). Towards ecological self: Deep Ecology meets constructionist self-theory. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 16, 93 - 108. Brookes, A. (1998). Place and experience in Australian outdoor education and nature tourism Paper presented at the Outdoor Recreation - Practice and Ideology from an International Comparitive Perpective. Brookes, A. (2002a). Gilbert White never came this far South. Naturalist knowledge and the limits of universalist environmental education. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 7(2), 73 - 87. Brookes, A. (2002b). Lost in the Australian bush: outdoor education as curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 34(4), 405 - 425. Casey, E. S. (1993). Getting back into place: toward a renewed understanding of the place-world. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. Casey, E. S. (1997). The fate of place: a philosophical enquiry. Berkeley: University of California Press. Collins, S. (2004). Ecology and ethics in participatory collaborative action research: an argument for the authentic participation of students in educational research. Educational Action Research, 12(3), 347 - 362. Conn, S. A. (1995). When the earth hurts, who responds? In T. Roszak, M. E. Gomes & A. D. Kanner (Eds.), Ecopsychology: restoring the earth, healing the mind. San Francisco: Sierra Club. Cotton, T., & Griffiths, M. (2007). Action research, stories and practical philosophy. Educational Action Research, 15(4), 545 - 560. Curthoys, L. P. (2007). Finding a place of one's own: reflections on teaching in and with place. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 12, 68 - 79. Feld, S., & Basso, K., H. (Eds.). (1996). Senses of place. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press. Fox, W. (1995a). The Deep Ecology - Ecofeminism debate and its parallels. In G. Sessions (Ed.), Deep Ecology for the 21st century: readings on the philosophy and practice of the new environmentalism (pp. 267 - 289). Boston: Shambhala. Fox, W. (1995b). Towards a transpersonal ecology: developing new foundations for environmentalism. Dartington: Green Books. Gough, N. (2008). How do places become 'pedagogical'? MUP Academic Monograph Series. Gruenewald, D. A. (2003). Foundations of place: and multidisciplinary framework for place-conscious education. American Education Research Journal, 40(3), 619 - 654. Gruenewald, D. A., & Smith, G. A. (Eds.). (2008). Place-based education in the global age: local diversity. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Heidegger, M. (1971). Poetry, language, thought. New York: Harper Collins. Henderson, B. (2001). Skills and ways: perceptions of people/nature guiding. Journal of OBC Education, 7(1), 12 - 17. Hernandez, B., Hidalgo, M. C., Salazar-Laplace, M. E., & Hess, S. (2007). Place attachment and place identity in natives and non-natives. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 27, 310 - 319. Horesh, T. (1998). Discovering and providing for the experience of nature. The Humanistic Psychologist, 26(1 / 3), 301 - 311. Hunter, J. (1995). On the other side of sorrow: nature and people in the Scottish Highlands. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing. Jackson, W. (1994). Becoming native to this place. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. Kidner, D. W. (2001). Nature and psyche: radical environmentalism and the politics of subjectivity. Albany: State University of New York Press. Knapp, C. E. (2005). The 'I - thou' relationship, place-based education, and Aldo Leopold. Journal of Experiential Education, 27(3), 277 - 285. Korpela, K., & Hartig, T. (1996). Restorative qualities of favourite places. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 16, 221 - 233. Krupat, E. (1983). A place for place identity. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 3, 343 - 344. Lukenchuk, A. (2006). Traversing the chiasms of lived experiences: phenomenological illuminations for practitioner research. Educational Action Research, 14(3), 423 - 435. Macauley, D. (2006). The place of the elements and the elements of place: Aristotelian contributions to environmental thought. Ethics, Place & Environment, 9(2), 187 - 206. Mackenzie, A. F. D. (2002). Re-claiming place: the Millenium Forest, Borgie, North Sutherland, Scotland. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 20, 535 - 560. Mackenzie, A. F. D. (2004). Place and the art of belonging. Cultural Geographies, 11, 115 - 137. Mackenzie, A. F. D. (2006a). A working land: crofting communities, place and the politics of the possible in post-Land Reform Scotland. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, NS(31), 383 - 398. Mackenzie, A. F. D. (2006b). "'S Leinn Fhein am Fearann" (The land is ours): reclaiming land, re-creating community, North Harris, Outer Hebrides, Scotland. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 24, 577 - 598. Malpas, J. E. (1999). Place and experience: a philosophical topography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Martin, P. (2004). Outdoor adventure in promoting relationships with nature. Australian Journal of Outdoor Education, 8(1), 20 - 28. Martin, P., & Thomas, G. (2000). Interpersonal relationships as a metaphor for human-nature relationships. Australian Journal of Outdoor Education, 5(1), 39 - 45. Massey, D. (2005). For space. London: Sage. Merleau-Ponty, M. (1968). The visible and the invisible. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. Meyers, R. B. (2006). Environmental learning: reflections on practice, research and theory. Environmental Education Research, 12(3), 459 - 470. Nash, R. (1982). Wilderness and the American mind. New Haven: Yale University Press. Nicol, R. (2003a). Outdoor Education: research topic or universal value? Part three. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 3(1), 11 - 27. Nicol, R. (2003b). Outdoor environmental education and concept-based practice: some practical activities designed to consider the relationship between people and place. Paper presented at the Sharing diversity and building European networks: the 6th European conference of environment outdoor education, Czarnocin. Nicol, R., & Higgins, P. (1998). A sense of place: a context for environmental outdoor education. In P. Higgins & B. Humberstone (Eds.), Celebrating diversity: learning and sharing cultural differences (pp. 50 - 55). Buckinghamshire: European Institute for Outdoor Adventure Education and Experiential Learning. Paasi, A. (2004). Place and region: looking through the prism of scale. Progress in Human Geography, 28(4), 536 - 546. Payne, P. (1999). The significance of experience in SLE Research. Environmental Education Research, 5(4), 365 - 381. Preston, L. (2004). Making connections with nature: bridging the theory-practice gap in outdoor and environmental education. Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 8(1), 12 - 19. Preston, L., & Griffiths, A. (2004). Pedagogy of connections: findings of a collaborative action research project in outdoor and environmental education. Australian Journal of Outdoor Education, 8(2), 36 - 45. Reason, P. (1998). Political, epistemological, ecological and spiritual dimensions of participation. Studies in Cultures, Organisations and Societies, 4, 147 - 167. Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (1999). Handbook of Action Research. Retrieved 24th June, 2008, from http://www.bath.ac.uk/carpp/publications/index.html Reason, P., & Heron, J. (2008). A laypersons guide to participative inquiry. Retrieved 1st September, 2008, from http://www.bath.ac.uk/carpp/publications/coop_inquiry.html Rogan, R., O'Connor, M., & Horwitz, P. (2005). Nowhere to hide: awareness and perceptions of environmental change, and their influence on relationships with place. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 25, 147 - 158. Rogers, T. (2000). In search of a space where nature and culture dissolve into a unified whole and Deep Ecology comes alive. Trumpeter, 16(1). Sale, K. (1985). Dwellers in the land: the bioregional vision. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books. Sarbin, T. R. (1983). Place identity as a component of self: an addendum. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 3, 337 - 342. Schama, S. (1995). Landscape and memory. New York: Vintage Books. Schroeder, H. W. (2007). Place experience, gestalt, and the human-nature relationship. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 27, 293 - 309. Seamon, D., & Mugerauer, R. (Eds.). (1985). Dwelling, place, and environment: towards a phenomenology of person and world. New York: Columbia University Press. Sessions, G. (Ed.). (1995). Deep Ecology for the 21st Century: readings on the philosophy and practice of the new environmentalism. Boston: Shambhala. Shapiro, E. (1995). Restoring habitats, communities, and souls. In T. Roszak, M. E. Gomes & A. D. Kanner (Eds.), Ecopsychology: restoring the earth, healing the mind. San Francisco: Sierra Club. Smith, G. A. (2002). Place-based education: learning to be where we are. Phi Delta Kappan, 83, 584 - 594. Sobel, D. (2004). Place-based education: connecting classrooms & communities. Great Barrington: The Orion Society. Stewart, A. (2003). Reinvigorating our love of our home range: exploring the connections between sense of place and outdoor education. Australian Journal of Outdoor Education, 7(2), 17 - 24. Stewart, A. (2006a). Outdoor education as neo-colonialism? Cultural and geographical specificity in outdoor education. Paper presented at the Third International Outdoor Education Research Conference, University of Central Lancashire, Penrith, Cumbria. Stewart, A. (2006b). Seeing the trees and the forest: attending to Australian natural history as if it mattered. Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 22(2), 85 - 99. Stewart, A. (2008). Whose place, whose history? Outdoor environmental education pedagogy as 'reading' the landscape. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 8(2), 79 - 98. Szerszynski, B. (2006). Local landscapes and global belonging: towards a situated citizenship of the environment. In A. Dobson & D. Bell (Eds.), Environmental citizenship (pp. 75 - 100). Cambridge: MIT Press. Thomashow, M. (1998). The ecopsychology of global environmental change. The Humanistic Psychologist, 26(1 / 3), 275 - 300. Tuan, Y.-F. (1974). Topophilia: a study of environmental perception, attitudes and values. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. Tuan, Y.-F. (1977). Space and place: the perspective of experience. London: Edward Arnold. Turner, J. (1995). 'In wildness is the preservation of the world'. In G. Sessions (Ed.), Deep Ecology for the 21st century: readings on the philosophy and practice of the new environmentalism (pp. 331 - 338). Boston: Shambhala. White, J. (1998). An tir, an canan, 'sna daoine (the land, the language, the people): outdoor education and an indigenous culture. In P. Higgins & B. Humberstone (Eds.), Celebrating diversity: learning by sharing cultural differences. Buckinghamshire: European Institute for Outdoor Adventure Education and Experiential Learning. Woodhouse, J. L., & Knapp, C. E. (2001). Place-based curriculum and instruction: outdoor environmental education approaches. Thresholds in Education, Aug/Nov, 31 - 34. Young, D. A. (2002). Not easy being green: process, poetry and the tyranny of distance. Ethics, Place & Environment, 5(3), 189 - 204.