Migratory System of Goat and Sheep Rearing

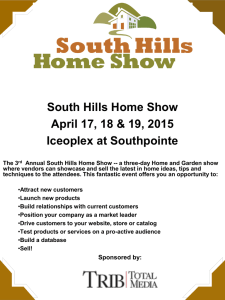

advertisement

Migratory System of Goat and Sheep Rearing in Himachal Pradesh - India Bimal Misri Regional Research Centre Indian Grassland and Fodder Research Institute HPKV Campus, Palampur - 176062 (India) Introduction Migratory pastoralism is very common in the Himalaya and a number of nomadic communities practise this . Though with the changing times and availabilty of diverse occupations a considerable decline has taken place in the number of pastoral nomads, yet this system is still the only occupation of a large Himalayan population. Gaddi is a distinct tribe of nomadic pastoralists found in the Himachal Pradesh state of India. This small Himalayan state (total geographical area 55673 thousand ha) is situated in the north-west of india, flanked by Jammu and Kashmir state on its north west, Uttar Pradesh on its east and Punjab on its south. The Gaddis, in all probability, have derived their name from their native land, the Gadheran which lies on both sides of the Dhauladhar ranges. These ranges begin on the right bank of river Beas and extend upto Chamba and Kangra districts. These ranges have a number of peaks as high as 5500 m above sea level, though the average altitude is about 2500m. In its north -east the Dhauladhar leads to the higher Himalaya, while towards its south west it touches the Shiwaliksthe lesser or outer Himalaya which merge into the plains.This continuity of the plains upto the higher Himalayan ranges offer an excellent migratory route to the Gaddis. Gaddis are distinct people wearing a characteristic and striking costume and they form an ixogamous union of castes of Rajputs, Khatris, Ranas and Thakurs. They are distinct from other nomads in having a permanent house anywhere. During migrations, the elders of the family and the women live in these houses. Gaddi habitations are situated on the Dhauladhar between an altitude of 1000 - 2500 m. Oflate some of the Gaddis have migrated to other districts of the state but the majority still lives in Bharmour region of Chamba. Out of a total population of 76, 859; 76,037 live in the region while 827 live in other nine districts. The fate of Gaddis living in Kangra district is unique. They have not been recognized as a tribe by the local state Govt., inspite of the fact that they number between 28,000-31.000. However, culturally and ethnically they are identical to the ones living in Bharmaur or elsewhere. While 30 percent of the Gaddis are still fully migratory, 70 percent have adopted to sedentory or semi-migratory mode of life. Many have shifted to other professions like Government jobs etc. Another major migratory, pastoral tribe found in the area is the Gujjar tribe. They number 26,659 and are different from Gaddis in their ethnicity, livestock rearing practices and migratory patterns (Anonymous, 1995). The present study was confined to the Gaddi tribe only. During the second meeting of the Temperate Asia pasture and fodder working group held at Dehradun during 1996 it was felt that it is essential to undertake detailed studies on the migratory systems of livestock rearing in the 32 Himalyan countries so that the present potential and the threats to these systems could be enumerated (Singh 1996). This paper is an outcome of a study undertaken on the Gaddi tribe of the Himachal Pradesh state of India. Material and Methods : The study was undertaken as per the proforma developed at the second meeting of the working group and later published after scrutiny by eminent workers and modifiactions suggested by them (Singh, 1996). The obervations were recorded in the printed off copies of this proforma. The recording of data was not confined to only the tenth stopover. In some cases even five stop overs were covered at a stretch, while in some cases (mostly at higher altitudes) the requirement of tenth stopover could not be adhered to. This was because of the logistics of the migration. Since the entire south west boundary of Himachal Pradesh adjoins the plains, there are numerous migratory routes which are selected by various families according to their grazing rights which have been established by way of usage since very long time. The significant feature of these routes is that the grazier's home falls on the route chosen by him. For present study following route was chosen since the homes of the graziers are situated around Palampur and this facilitated the data recording about the family and sedentary activities. Bilaspur - Kaloli - Hamir Sidh - Bijri -Saloni - Hatera - Talashi - Hamirpur Mauri - Alampur - Pinala - Bhaura Van - Palampur - Gwal Tikkar - Utrala Dunhi - Parai - Jaloos(Jeet) - Chani (Holi Banghal). Though data were recorded from all the graziers encountered enroute but three families were selected for continuous observations. These families belonged to Messers Singhu Ram, Balak Ram and Jagdish Chand. The obervations recorded were both visual and actual. For determining the botanical composition and biomass 1x1 m replicated quadrates were laid out. The vegetation was manually clipped and weighed by a spring balance. The vegetation was seperated into different species and their names were recorded. Incase of inability to identify the species, the specimens, after assigning a code number were carried to the research centre for identification. Representative samples were oven dried to determine dry weight. These samples were analysed for nutritional parameters. Representative soil samples were collected from all the altitudes for the determination of pH etc. For other observations, interviews were conducted with the graziers and field observations were recorded. The data presented is in the form of averages with range. Migratory routes and camping sites These are well defined, unmarked routes which initiate in the plains and after passing through the lesser Himalaya i.e., Shivaliks where the dominant vegetation is scrub forest; cross over the middle Himalaya supporting open grazing areas and coniferous forests end into 33 the subalpine, alpine and arctic zones where the dwarf vegetation does not support trees and comprise, mostly, of grasses forbes and a few legumes. The migratory routes are only for the transit purposes and the flocks stay for most of the time either in the lower hills, plains or in the alpines. The transit from the plains or outerhills upto the alpine areas takes about three months. The time consumed is highly variable and depends upon the distance. Each flock covers 7-8 km per day starting the journey at 6.00 A.M. and breaking it at 6 P.M. Three stop overs are used for overnight stay while at the fourth stopover the flocks stay for two nights. This is done to wear off the fatigue. Even the choice of stay for two nights is elastic and at times it may not be the fourth stopover but a place where the relatives or a friend of the grazier lives or better fodder and grocery are available. This could mean a longer stay of 2-3 nights at second or a fifth stopover. The three flocks under investigation, however, spent two nights at every fourth stopover. This pattern of night camping continued upto Palampur, where the families stayed for fifteen days (1st March - 15th March). The movement upto middle hills is always prefered through the river valleys. The river sides provide a flat ground and easily accessible water resource. In case of rains and inclement weather the river sides provide some shelters in the form of rock hangings etc. Above all the movement is not as tiring as on the hill slopes. The graziers always carry a few aluminium utensils and a Tawa (steel pan) to make Chapatis (local bread). At every stopover a frugal meal is cooked which include chapatis, chutney (ground leaves of Aaonla/Tamarind/ Green Chillies and salt) and the goat milk. Occasionally, the goat milk is turned into cheese and eaten. It is normally done at the stopover where they stay fot two nights. At times, vegetables may also be purchased from the village market and cooked. Ninty percent of the graziers do not carry any night camping kit like a tent. They spend the night in open under their blankets. During colder nights even fires may be lit. The above described pattern of movement continues till the middle hills. Above this region the grade of the slope becomes even 70 percent at places and no suitable place is found for camping. Only a brief stopover is made for cooking a meal or a brief rest, otherwise the movement is continuous till the flat pastures in sub alpine or alpine regions are reached. Grazing Land According to the official statistcs, out of the total geographical area of 55,67300 ha, 12,23500 ha have been classifed as the permanent pastures and grazing lands (Anonymous 1995). However, it is very difficult to ascertain the actual area available for grazing. Besides the area under pastures, following additional area is also available for grazing and during migration these areas are extensively grazed. Forests a) Open forest b) Unclassified forest c) Forests not under the control of Forest Deptt. 33,34982 ha 86,848 ha 94,770 ha 34 Fallow land Culturable Waste Unculturable Waste 55,700 ha 1,26,400 ha 1,90,600 ha The entire grazing area is spread over in three zones, creating three distinct range types. These types are : Sub tropical ranges of lower hills Subtemperate - temperate ranges of mid hills Alpine ranges of high hills. The altitudinal range varies from 300-4500 m above sea level. The area is spread over undulated, slopy and hilly terrain with slope grade ranging between 30-70 percent. The soil characteristis of the three zones are summarized below : 1. Subtropical ranges of lower hills : The soils are alluvial-loamy with shallow depths at the slopes; deficient in available nitrogen ; low - medium in available potassium. The soil reaction is neutral and the texture varies from loamy sand to sandy loam. 2. Sub-temperate-temperate ranges of mid-hills : The soils are grey brown, podzolic brown; shallow-deep; neutral-highly acidic. Available nitrogen varies from mediumhigh; phosphorus low-medium and potassium availability is medium. 3. Alpine ranges of high hills : These soils correspond to alpine humus and mountain skeletal soils which are rich in organic matter. The texture is generally sandy loam to fine sandy loam. The available nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium are high. While the soil reaction is neutral-acidic. All the three distinct zones support diverse vegetation which is unique to each zones. The outer hills have scrub forests of Lantana camara, Acacias, Adhotoda vasica, Dedonia viscosa, Carissa etc. The herbaceous vegetation is very scarce and mostly comprise of grasses like Cynodon dactylon, Bothriochloa pertusa, B. intermedia, Imperata cylindrica, Saccharum spontaneum etc. At little higher altitudes the arboreal element is dominated by Pinus longifolia. In the middle hills the Pinus longifolia gets replaced by Cedrus deodara. The other shrubby plants are Cotoneaster racimiflora, Daphne oleoides, Desmodium tillaefolium, Indigofera heterantha, Parrotiopsis jaequemontii etc. The ground vegetation is dominated by grasses like Agrostis stolonifera, Andropogon tristis, Chrysopogon echinulatus, Dichanthium annulatum etc. Most Common trees found are Quercus incana, Rhododendron sps., etc. The highest zones support dwarf, mat like vegetation, mostly comprising of Poa triandra, Chrysopogon echinulatus, Andropogon ischaemum, Festuca alpinum. F. rubra etc. Very few trees of Betula utilis may be found. The bushy vegetation mostly comprise of Viburnum foetens, Sambucus wightiana etc. The climate of the study area is also very diverse. It varies from hot summer to the severe cold winters. The outermost Himalaya situated in the south of the state experiences as hot summer and a mild winter as the plains. This area also receive the monsoon rains and the total 35 precipitation ranges between 150-175 cm per annum. The maximum summer temperature goes up to 40°C while the minimum winter temperature goes down to 10°C. The climate of the mid hills is comparatively moderate. Both summers and winters are mild. The summer temperature may go upto 30°C while the minimum winter temperature may go down to an average of 5°C; though sometimes even the temperature may go down to freezing levels. The annual precipitation, including occasional light snowfall and monsoon rains ranges between 75-100 cm. The higher hills have typical cold climate. The maximum temperature during summer may not exceed 20°C and during winters the minimum temperature may go down to -2°C. The precipitation declines in these regions and may vary from 30 cm - 50 mm per annum, progressively decreasing with the increase in altitude. Botanical Composition : The biological diversity of the Himalaya is vertical and it is too variable at various altitudes. In between the altitudinal zones it is very common to find some ecological niches. The data collected on the botanical composition are massive and it may not be possible to present the entire data in this paper. However the percentage composition of grazing areas (which did not support bushes and trees) or Ghasnis, as these are locally known from three zones is presented in Table 1. The species composition presented in the Table 1 is only a general pattern. In reality the botanical composition is too degraded at the lower and middle hills. Apprarently the botanical composition of the higher hills seems to be too inadequate for the flocks but the weight gain by sheep and goats in these areas suggest otherwise. In lower hills from Bilaspur to Talashi the ground vegetation was by and large absent. Only the bushes and trees provided the necessary herbage. Sheep were observed browsing the leaves of Adhotoda vasica while the goats nibbled the stems of this bush dominantly found at these altitudes. Carissa, another bush commonly found was extensively browsed by the goats. The degradation in the lower hills may be upto stage 3-4 in a scale of 1-4. Table 1 Botanical Composition of Ghasnis (grasslands) of three hill zones of Himachal Pardesh ................................................................................................................................. Zone Species % Composition ................................................................................................................................. Lower hills Arundinelle nepalensis 7 Bothriochloa pertusa 11 Cynodon dactylon 6 Chrysopogon gryllus 13 Dichanthium annulatum 7 Eragrostis sps. 8 Imperata cylindrica 18 Saccharum spontaneum 22 Other grasses like Themeda etc 8 Mid hills Agrostis stolonifera and A. gigantea 13 Alopecurus myosuroides 7.6 Chrysopogon echinulatus 39.4 36 Dactylis glomerata 5 Dichanthium annulatum 4 Eragrostis sps. 3 Festuca rubra 1 Imperata Cylindrica 10 Pennisetum orientale 9 Poa pratense 5 Trifolium repens 2 Lotus corniculatus 1 High hills Agropyron sps. 6.3 Agrostis stolonifera 10.5 Andropogon ischaemum 10.5 Alopecurus myosuroides 4.2 Dactylis glomerata 15 Festuca alpinum 6.5 F. rubra 9 Lotus corniculatus 8 Pennisetum flaccidiom 13 Poa alpina 7 Phleum alpinum 6 Trifolium repens 4 ................................................................................................................................. The most common and predominant weeds of the lower hills are Ageratum conyzoides, A. houstonianum, Lantana camara Eupatorium odoratum and Parthenium hysterophorus. Flock Composition The livestock population of Himachal Pradesh state comprise of 21, 51, 616 cattle, 70, 0923 buffaloes, 10,74,345 sheep, 11,15,591 goats and 14,094 horses. It may be very difficult to make an exact estimate of migratory sheep and goats but these may form about 70 percent of the total goat and sheep population of the state. As far as the migratory pattern of livestock rearing is concerned it is only sheep and goats which are reared under this system. The migratory herds are classified under 3 categories. Small flocks consist upto 100 animals having 60 sheep and 40 goats ; medium flocks consist 300-500 animals while the Large Flocks comprise of 1000-1500 animals. The average composition of the flock remains same in all the categories with 60 percent sheep and 40 percent sheep. Each flock includes 2-3 dogs. The large herders also have 4-5 ponies to carry the essential supplies etc. The migration and its management The migration is essentialy associated with finding better forage resources. During winter months i.e. late October-early November to late February - early March the flocks stay in outer hills or the plains which are locally known as Kandi Dhar. These areas are also Known as Ban and in Kangra district these areas are claimed by Gaddis as Warisi i.e., inheritance. In historical 37 past these areas were granted by the local kings as gifts to the Gaddi families and the grazing rights are still maintained by the inheritors. The holder of the grazing rights is known as Mahlundi and in the old days he would pay a tax to the King and in turn would collect it from the Gaddis who would graze their flocks in his area. Now the situation has changed and the tax for the inherited area is paid to the Government. However, a Gaddi is free to let others graze their animals in his area against the payment of fee which may be in cash or kind. In these areas the owners of the cultivated lands often offer their fallow land to the flocks for grazing of the aftermath of last crop which is rice. The flocks in the process adequately fertilize, these lands and the land owners pay a fee to the flock holder. Now-a-days this fee consists of providing the full rations required by the Gaddi flocks holder during the duration of the field grazing. The upward movement starts in the month of March or after 15th of February depending upon the length of the migratory route. In the case of farmers under observation in this study, they started their upward movement on 10th February. In case of the small holders it is always the owner and his family members who accompany the flocks. The medium sized flocks are also accomanied by the owner but in certain cases contractual graziers known as Puhals are engaged. In case of the large flocks, the owners always prefer to stay back and the Puhals are engaged for the migration of flocks. Puhals may be friends or the natives of one's own village. The Puhals have to be provided food in the form of maize flour and other essentials of food. For this an advance payment is made or in case of the large flocks adequate quantities are provided which are hauled by the horses accompanying the flocks. In case of this study each herders had two accomplices with him and the flocks had the following composition. Singhu Ram 270 sheep 163 goats total 433 Balak Ram 203 sheep 157 goats total 360 Jagdish Chand 302 sheep 187 goats total 489 After leaving the outer hills, the flocks travel upto the middle hills through river valleys. The roads are always avoided. Enroute, the flocks are managed by the graziers and their dogs. All the three flocks scattere to different sides but assemble at the pre-fixed stop over during night. Each flock is lead by one of the graziers ; one remains at the tail end and the yongest of the three keeps on running here and there to avoid straying of the animals. Tresspassing of the animals into reserved and closed forest areas has to be avoided. In order to regulate the grazing and verify the payment of taxes Rahdari check post have been established on all the migratory routes. The checkposts were established by the erstwhile kings but now these are managed by the Forest Department. By 10th March the graziers reached their homes at Palampur and it is a great time to rejoice. The flocks are stationed in fallow lands for fertilization. It is the major reason for a long stay at homes. A goat is slaughtered to celebrate the home coming. During the stay at home the graziers prepare for onward journey in colder places by mending their clothes or even they procure new ones. The essential repairs of the houses are done and all other matters relating to the family affairs are settled. This is also the marriage time in the family when marriages of the young ones are ceremonized. 38 The further journey upto the alpines is more arduous. There are very few stopovers and the steep slopes are difficult to traverse. After reaching the alpines, it is a great time to rest and organize the day to day routines. In alpines, the areas for grazing are again earmarked. Though there are no boundaries on the field, the Gaddis by a continuous usage know their boundaries. The tresspassing into each others areas is always avoided and this fact is ethically adhered to. However, in case of any dispute, the entire community gathers and solves the dispute. The downward journey is also faced with the same problems and is performed according to the same routines. The time of commencing upward or downward journey commensurates with the marketing of the animals and mating of the animals. In March the traders start coming to the graziers and strike deals for the purchase of animals for meat purposes. Similarily during downward movement, the traders arrive in September when the sale transactions take place. The process of migration is very tough and has its unique problems. Enroute there are frequent attacks on the flocks by wildlife, particularily the Cheetahs (leopard). The Gaddi dogs are very brave and they always have a spiked band around their necks to avoid lifting by a cheetah. Inspite of the dogs and a constant vigil by the graziers upto 10 percent of the flock is destroyed by the wild life. In case of a natural death of the animal, the flesh is cut into slices and dried which is eaten later. Inspite of the numerous vagaries of migration, the Gaddis, love it and enjoy it. Range production The biomass production varies a great deal in various zones. The botanical composition and the percentage composition is also different in different zones. The estimations for the present study were made after laying out quadrates of 1 X 1 m size. The quardrates were replicated (3-5); the frequency of replications depended upon the area of study. In case of larger grazing areas 5 quadrates were laid; while smaller areas were scored by 3 quadrates. The herbage estimations were made only from the grass or herbaceous vegetation dominated areas. The observations were recorded at the stopovers or about 2 km short of the stopover. This was necessiated since the stopovers are the most convenient place to encounter the graziers. The mean figures about the biomass production and its nutritive value are only representative and generalized. (Tables 2 and 3). The values vary a great deal. Since the alpines were the priority area of this study, observations were recorded during actual stay of the animals over there. In case of middle and lower hills the observations were recorded during mon-soon and post monsoon period which is the most productive period. During March-June these areas are absolutely dry and the production figures are very low. The estimations about the biomass during this period at lower and middle hills have been made by Misri and Sareen (1997) and the same are presented in Table 4. During October-February, the winter months all the grasslands are dormant and the growth is arrested. During this period the migratory flocks depend on the scrub vegetation of the forests, while the sedentary livestock is fed crop residues and hay. The flock owner's reactions to the question of availability of herbage were very interesting. Inspite of the low levels of biomass production in the alpines, they are more than 39 satisfied with the production levels and the species composition of the pastures. Goat and sheep gain 8-12 kg of weight in the alpines and the Gaddis atttribute it to Neeru grass (Festuca gigantea). They are also happy with the available foreage resources enroute the migration. They are only concerned about their winter abode i.e. the outer hills and adjoining plains where they stay during winter. The closure of forest areas and low levels of forage production in river valleys are a matter of concern for them. They would like the plantation of grasses, fodder bushes and trees in this area and would like the Government to open more forest areas for their flocks. ................................................................................................................................... Table 2 Biomass Production of grasslands in various zones. (Dry matter t/ha) (Means given in parenthesis) ................................................................................................................................... Zone Months July August September Mean ................................................................................................................................... Low hills 4.78-5.02 3.40-6.65 6.70-7.42 (4.9) (5.02) (7.06) 5.66 Middle hills 2.32-4.57 3.65-4.32 3.90-5.13 (3.44) (3.98) (4.51) 3.97 High hills 1.41-1.94 1.93-2.87 2.32-2.84 (1.67) (2.4) (2.58) 2.21 ................................................................................................................................... Table 3 Nutritive value of the pasture herbage in various zones (percentage in dry matter) Mean values ................................................................................................................................... Parameters July August September Mean ................................................................................................................................... Lower hills Dry matter 35.13 40.72 43.67 39.84 Crude protein 4.32 4.87 3.91 4.36 NDF 69.25 70.29 75.62 71.72 ADF 43.12 46.22 48.12 45.82 Calcium 1.32 1.12 1.31 1.25 Phosphorus 0.13 0.16 0.14 0.14 Middle hills Dry matter 32.80 39.25 43.14 38.40 Crude protein 8.27 10.22 10.13 9.54 NDF 71.32 71.76 74.27 72.45 ADF 37.33 38.46 41.12 38.97 Calcium 1.29 1.47 1.63 1.46 Phosphorus 0.11 0.17 0.16 0.15 High hills Dry matter 33.26 31.16 39.9 34.77 Crude protein 10.10 9.78 10.32 10.04 NDF 58.32 62.51 67.11 62.65 40 ADF Calcium Phosphorus 35.10 0.83 0.19 34.70 0.91 0.13 42.12 1.13 0.17 37.31 0.96 0.16 ................................................................................................................................... Table 4 Biomass production at lower and middle hills during March-June (t/ha) ................................................................................................................................... Month Fresh Wt. Dry Wt. ................................................................................................................................... Lower hills March 3.24 0.83 April 3.10 0.83 May 2.76 0.66 June 1.76 0.44 Middle hills March April May June 1.59 3.08 6.62 1.36 0.30 0.47 7.20 0.35 Fodder Trees Fodder trees constitute a major proportion of livestock feeding in the middle Himalayan hills. It has been estimated that fodder trees and shrubs contribute green forage to the extent of 10-15 percent during monsoon; 80 percent during winters and 60 percent in summers to the rations of ruminants in the Himalayan hills. Besides being found on common property lands and forests, the fodder trees are grown by farmers on their farm bunds, terrace risers and homesteads. 84 major fodder trees and 40 shrubs have been reported from the Himalayan region to be of very high forage value (Misri and Dev, 1997). As far as the migratory graziers are concerned, they do not own the fodder tree plantations anywhere. However, they use the fodder tree leaf wherever available. The trees growing in open forests and road sides are regularly lopped by the graziers. Sometimes, the illicit lopping is done in the reserved forests as well. At times, the tree leaf fodder is purchased during the migrations from the adjoining villages. The tree fodder is either fed at stopovers or during winter stay in the outer hills. The tree plantations are at an approachable distance say .5-1 km away from the stopovers. The migratory graziers as well as the sedentary farmers have remarkable traditional wisdom about fodder tree leaf feeding. Most of the fodder trees contain tanins and other toxic 41 constituents at a certain stage. In order to avoid the feeding of leaves at this critical stage, the graziers have perfected a calender for fodder tree use as per the following sequence : From April-June : Morus alba, M. serrata, Leucaena leucocephala, Robinia pseudoacacia, Albizzia lebbeck, Ficus glomerata, F. religiosa, F. roxburghii. From July -October : Mostly grazing ; since adequate grasses are available during this postmonsoon period. From Nov-March : Bauhinia variegata, Grewia optiva, Terminalia arjuna, Dendrocalamushamiltonii. The leaf biomass production of six most important trees is presented in Table 5. .................................................................................................................................. Table 5 Leaf Biomass production of important Fodder Trees. ................................................................................................................................... Tree species Age at lopping (yrs) Leaf Biomass (Kg/tree) ................................................................................................................................... Bauhinia variegata 8-10 15-20 Dendrocalamus hamiltonii 8-10 30-40 Grewia optiva 8-10 12-15 Quercus incana 10-12 8-10 Robinia pseudoacacia 6-8 10-15 Terminalia arjuna 8-10 40-50 ................................................................................................................................... Nutritive value and farmers scoring for preference of some important fodder trees of the region are presented in Table 6. Table 6 Crude protein (%) in dry matter and farmer scoring in order of preference of some Himalayan trees. ................................................................................................................................... S.No. Species C.P.(%) ................................................................................................................................... 1. Aegle marmelos 15.33 15 2. Albizzia lebbeck 18.94 21 3. Artocarpus chaplasha 18.14 20 4. Bauhinia variegata 15.91 17 5. Bambusa nutans 14.09 10 6. Bauhinia vahlii 12.81 6 7. Cordia Dichotma 12.37 5 8. Cedrela toona 14.82 12 9. Celtis australis 15.33 14 Score 42 10. Dendrocalamus hamiltonii 18.72 4 11. Eugenia jambolana 10.56 2 12. Ficus glomerata 13.93 8 13. F. benghalensis 10.29 1 14. Grewia optiva 20.00 3 15. Leucaena leucocephala 15.22 13 16. Litsea glutinosa 14.60 11 17. Morus alba 16.64 19 18. Quercus incana 11.42 7 19. Robinia pseudoacacia 20.45 9 20. Salix tetrasperma 13.19 16 21. Terminalia arjuna 13.98 18 ................................................................................................................................... Land Tenure Prior to the middle of last century the forests and pastures were nobody's concern. However, with increasing pressure on these natural resources and an imminent threat to their existence, first national Forest Law was passed in 1865. It was the first attempt to give absolute powers to the Government to regulate most of the forests and pastures. The major outcome of this law was the regulation of grazing in the forests to permit the regeneration of tree species. Subsequentaly the Kangra Land Settlement was carried over during 1865-1872 which led to the promulgation of 1878 Forest Law. According to this Law a system of Reserved and Protected Forests was introduced to regulate most forests and the grazing lands. The settlement earmarked grazing areas for each Gaddi family and the size of the flock was fixed. The migratory routes for each family were also fixed and it was provided that each flock will move atleast 5 miles each day stopping for one night at a stopover. The Gaddis did not appreciate these controls. Thereafter the status of forests and pastures remained an important issue for discussions and evaluation by many experts like Mr. Hugh Cleghorm and Sir Dietrich Brandis. Acting on the observations made by Mr. Hart regarding the deteriorating condition of the pastures in Kullu area, the local forest settlement proposed a ban in 1920 on grazing by the local flocks. However, the migratory flocks were exempted from this ban. Goats were identified as a major threat to the grazing areas and during 1915 farmers were asked to pay a higher grazing fee for goats, even the sedentary goats were brought under this regulation. After independence following commissions were appointed to rationalize the grazing and thereby regulate the land tenure (Verma, 1996). 1. 1959 The H.P Govt., Commission on Gaddis 2. 1970 The H.P Govt., Commission on Gaddis The second commission recommended a freeze in the size of the flock. During 1972 the state Govt., again issued some orders for regulating the flock size. But due to political compulsions none of the decesions were ever imlplemented with strict measures. 43 The present situation is almost fluid and the allocation of grazing lands and migratory routes made during 1865 - 1872 land settlement is adhered to. The farmers are not the owners of the land but as per the usage since centuries they have the grazing rights over these areas which pass over as inheritance in the family. However, the graziers have to renew their permits each year by paying a grazing fee of Rs 1.00 each sheep and Rs 1.25 per goat. The permits contain the details about the flock, area of grazing and the migratory route to be used. Community and House Hold The Gaddi community is a very small community (total number about 100,000) though very well knit and spread over a large area of Himachal Pradesh. They have a very rich history of ruling the Gadheran, their native land and the mention of their erstwhile Kings is very common in their folk tales and songs. Most of the historians have traced their origin to Delhi and Lohore. Gaddis are superstitious, god fearing, kind, honest and hard working people and practise Hinduism as their religion. Only 18 individuals practising Islam as religion have been reported from Bilsaspur (13) and Shimla(5) districts. Gaddis follow partiarchial and patrilineal type of family system. Father, the head of the family is responsible to look after the interests of each member of the family but the mother is equally responsible and works hard, and to some extent, harder than the father in field and house. Because of their liberal approach the nucleus families are very common. After 2-3 years of marriage a son is encouraged to start his individual family; 75 percent families are nucleus while only 25 percent, mostly migratory, families are extended. Though most of the families may be nucleus, yet they are woven in geneologically defined social bonds. They are grouped in Tols (Groups or Clans). Each Tol consists of 2-3 generations of the same ancestary. Every village is headed by an elder known as Pradhan and every body abides by his decesions. A group of villages are organised into Panchayats, the recognized system of local governance. Local disputes are settled at the level of Pradhan where as disputes between the villages are settled by the Panchayet. Gaddis, generally have a small family. The families of three samples studied are described below : 1. Mr. Singhu Ram (self) Mrs. Singhu Ram, Three sons all above 16 years. Total members 5 2. Mr. Balak Ram (self) Mrs. Balak Ram, mother and father of Balak Ram, Two sons aged 11 and 9 one daughter aged 6. Total members 7. 3. Mr. Jagdish Chand (Self), Mrs. Jagdish Chand mother and father, one brother, 2 sons both above 16 years ; total members 7. Out of three, Balak and Jagdish are literate. Both have gone to school upto 5th and 6th standard respectively., All the women and singhu are illiterate. Singhu's three sons can read and write and have gone to school only upto 4th standard. Balak's both sons are going to school, Jagdish's brother has studied upto 6th standard and both his sons have also gone to school upto 3rd and 4th standard. This group indicates 52 percent literacy. But this is not indicative of the general situation. All the three families oberserved have their homes near Palampur where excellent educational facilitis are available. The situation in some of the remote places like Bharmour is absolutely different where adequate and convenient aducational facilitis are not 44 available. Incase of the entire community the literacy percentage is 30. Of late, due to the introduction of some social welfare schemes like free education, books, uniforms, lunch and cash incentives for Gaddis and other weaker sections of the society, the situation is really going to change. The male members are exclusively responsible for the rearing of migratory flocks. As far as the sedentary agricultural activities are concerned, the lands are ploughed and sown by the male members. Clodding and weeding is done by the women members; harvesting is done jointly. Tree fodder is collected by the men folk whereas the livestock rearing both grazing of animals and collection of fodder from forest areas is done by the women. Firewood is also collected by the women. As far as working for other households is concerned, it is common only around urban areas like Kangra, Chamba or Palampur. Almost 45 percent women do a partime job in 2-3 houses every day spending 4-6 hours each and earning Rs. 600-800 per month. Sometimes the graziers carry their families to outer hills or plains during winters. The women may work in other households if their winter stay is near the urban areas. Crops Crops have no role to play in the migratory systems of the Gaddis since the migratory flocks are not fed any crop residues. The sedentary Gaddi's cultivate the small holdings which vary between .25-1 acre of land per family. These lands have, invariably been provided to the sedentary families after the introduction of agrarian reforms in the state. The major crops are: Rice, Wheat, Maize and Barley. Rice is transplanted during July, wheat is sown in early November, Maize is sown between 20th May and 20th June while Barley is sown after snow melt at higher altitudes and early November at lower altitudes. The average yields and grain straw ratios are given in Table 7. ................................................................................................................................. Table 7 Yield of grain and straw of major food crops ................................................................................................................................. Crop Sowing time Grain yield Grain-straw ratio (t/ha) ................................................................................................................................. Rice June-July 2.0-2.5 1:5 Wheat Early-Nov. 1.8-2.0 1:1 Maize 20th May-20th June 3.0 1: 1.5 Barley Early Nov or 1.8-2.0 1:1 April ................................................................................................................................. In most of the cases, the grain or the straw is not sold but conserved for domestic use. It is only in case of the rich Gaddis that surplus grain may be sold. However, the crop residues are not sold. 45 Livestock The flock composition of Gaddis has been described elsewhere. Gaddis posessing 250 and above animals are generally considered to be well off. The major livestock products and their availability pattern is described below. Wool : The sheep are sheared thrice a year and the production of wool is as below : January 500 gm/sheep April/May 800 gm/sheep September 1.5 kg/sheep Total each sheep 2.800 kg/sheep The wool is basically collected for selling. The traders know the routes and the time of shearing and accordingly reach the appropriate places to purchase the wool. The selling rates are fixed by the Government. The present rate is Rs. 65.00 per kg of mixed wool. The black coloured wool is held in high demand but after the introduction of sheep improvement programmes, most of the wool available is either white or shades of white. Black sheep also fetches a higher price as the black wool. At an average 5 percent of the wool produced is held at home for weaving of clothes for domestic use. Meat : The live carcass are sold at the beginning of upward or downward movement. The mother stock is maintained upto the age of eight years. Lambs and kids aged 3-6 months are sold in the plains or outer hills in March. The three month old lambs fetches a price of Rs. 350 while six months old may fetch Rs. 700 each. Kids of same age may fetch Rs. 250-350 more since goat is preferred for meat. At this age the body weight of lambs and kids is 9-12 kg. The second sale is held in september when downward migration starts. By this time the lambs and kids are fully grown and weigh between 20-22 kg. In this case also the traders go upto the subalpines and alpines to buy the animals. Sheep fetches a price of Rs 650 each while the goat may fetch Rs 750-850. Each herder sells 40 percent of sheep and 70 percent of goat every year, Though Gaddis are very apprehensive to reveal the real income but a fair estimate will be as following: 1. 100 animal herder; if sells 50 animals @ Rs 500 (average) Total income: Rs 25,000 / year 2. 350 animal herder; if sells 100 animals @ Rs 500 (average) Total income: Rs 50,000 / year 3. 1000 animal herder; if sells 300 animals @ Rs 500 (average) Total imcome: Rs 150,000 / year The expenditure is only Rs 1.00 per sheep and Rs 1.25 per goat as grazing fee. Ten percent animals ar lost due to wild life or other accidents. Some significant features connected wtih the livestock rearing by Gaddis are: 46 ¨ ¨ ¨ ¨ ¨ ¨ ¨ ¨ Health care provided by the Government is available only upto the middle hills. There are no facilities in the alpines. These facilities are also quite far away and unapproachable for the graziers. Most common ailments of the animals both sheep and goats are poisoning after eating the noxious and poisonous weeds. The animals bloat after eating Ageratum and Upatorium. The traditional cure is feeding salt to the animals. The other most common disorder in animals is the Lantana posioning. The animals get drowzy after eating Lantana. The local practices call for chopping off an ear to let the animal bleed till the posion is drained off. The graziers watch the activity of the animal and when they feel that the poison is drained off, a paste of mud is applied to the wound to stop bleeding. The other cure for mild Lantana poisoning is feeding goat milk after thinning it by adding lot of water. The goat milk is never sold. It may be given free of cost to the acquintances enroute. The only use of this milk is the consumption by the graziers or making cheese for self use. Since it is not a marketable commodity , the graziers have to spend a lot of time to stop the suckling kids from over feeding. The business in goat milk is considered unethical Besides open grazing the only supplement provided to the animals is the common salt. It is fed once a week to the animals by spreading it over the rocks at stopovers @ 3 Kg/100 animals. Incase of the death of animals. the flesh is cut into slices ond separated from bones; salt is rubber over and it is dried for future consumption. Hides are not sold but turned into bags to store and carry food items. The animal sacrifice is common on certain religious occasions , family celebrations or before crossing a pass in the hills. The animal meant for sacrifice (it is always a he goat) is first given a bath then the priest applies a paste of flowers and rice at its head and says prayers. A third person. who is not connected with the rearing of this animal, then kills it. The priest carries away the hide, head and one of the legs, the rest of the carcass is eaten by the family and friends. The important occasions for sarcrifice are; ¨ Putting new field under plough ¨ Removing the incapacity of field by improvement to grow wheat. ¨ Laying the foundation stone of a house. ¨ Celebrating births, get togethers and marriages. ¨ 12th and 14th day of a death in the family. ¨ Before the start of a journey. ¨ Before crossing a mountain pass. Lambing: There are two lambings in a year. The process of mating starts in September and by the time the flocks reach the winter abodes the sheep and goat are pregnant. Here, the animals get a comfortable stay and the lambing starts by end of February or in first fornight of March. It can extend upto April in certain cases. After the upward movement starts the process of mating is 47 repeated and the graziers prefer to start their downward movement after the second lambing completes in the alpines. The mortality rate of the lambs is five percent in the alpines and three percent in the outer hills. The twining percentage is only 10. Community Participation Because of their being busy with their affairs, an inherent quiet nature and a dislike for the Government officials, the respondent Gaddis were very apprehensive of the present investigation. However, with the help of some local contacts and mostly due to some locals working at our regional centre three families living around Palampur agreed to be the subject of this study. The scope of the present study was only investigative and not participatory. Still the following major points emerged out of the interractions with the flock herders- the Gaddis. ¨ ¨ ¨ ¨ ¨ They are happy the way they are: They are unaware of the fact that the forage resources can be improved. They are willing to cooperate in any endeavour of forage resource improvement. They are hesitant to reveal their economic status. They have started falling pray to the electronic media, particularly the cable T.V, which they watch while passing through urban areas. This exposure has resulted in the demand of providing schooling for the children, medical facilities etc. When asked whether they would leave the traditional migratory system, they were emphatic in replying that they could do it better if the entire system is improved. They would not agree for any enhancement of grazing fee; and are unware of the resources from where finances could be arranged for improvement of forage resources. They are ready to undertake any improvement measures in areas held by them as per usage, provided the inputs are provided by the Government. They would welcome to have seed for testing in their areas. They feel that the forage resources at the lower altitudes, where they stay during winters, are dwindling and this should be the priority area for improvement. ¨ ¨ ¨ ¨ ¨ ¨ Conclusions ¨ ¨ ¨ The migratory system of Gaddis has been going on for centuries and it shall go on since the economics of the entire system is profitable; of course with an input of very hard work; seperation from the family and an uncertain future. The present study is just a drop in the ocean; the entire system is so elaborate and perfect that with detailed studies spread over the entire state some conclusive results could be obtained. Till the above is done, it is very essential that one model migratory route is identified and a detailed project is formulated for its improvement. This could act as a model for various graziers of other areas. The funding sources for such a project may be identified. 48 References Anonymous 1995 Statistical Digest. Deptt. of statistics; H.P Govt; Shimla, India. Misri, B and Inder Dev. 1997 Traditional use od Fodder Trees in the Himalaya IGFRI Newsletter 4(1) Misri, B and S.Sareen 1997 Regeneration Dynamics of Mid-Hill Grasslands of Kangra Valley. Envis (accepted for Publication) Singh, P 1996 Workshop Proceedings II meeting of Temperate Asia Pasture and Fodder Working Group Dehradun, India pp 85 Verma, V 1996 Gaddis of Dhauladhar. Indus Publishing Company, New Delhi: pp 149 49