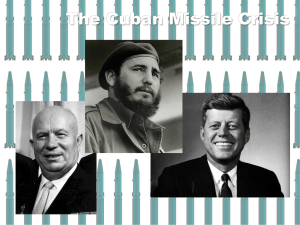

La crise de Cuba : documents américains

advertisement