+ MicrosoftWord - Louisiana State University

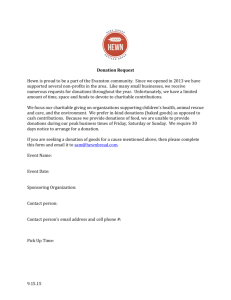

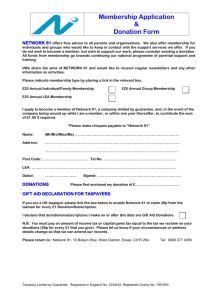

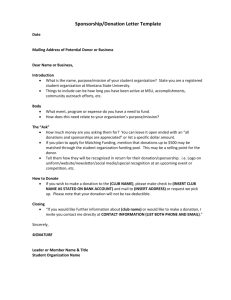

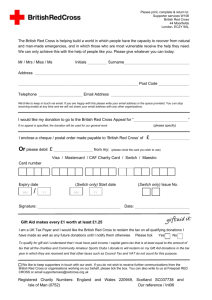

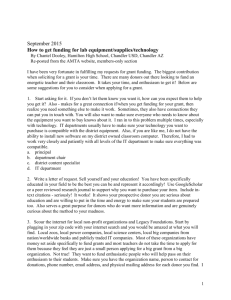

advertisement