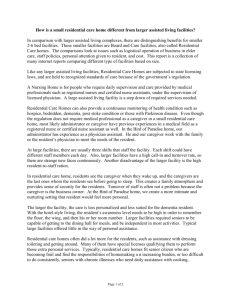

Residential Care for Individuals with Developmental Disabilities

advertisement