PAR

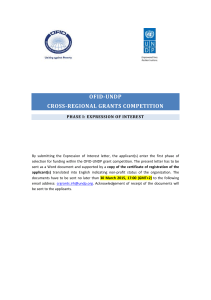

advertisement