Rome5key

advertisement

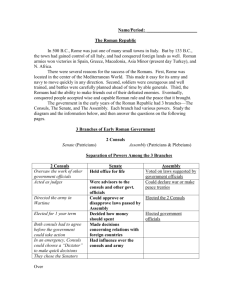

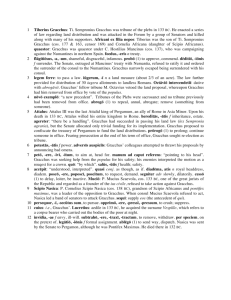

WH1: The Rise of Rome 5: The Gracchi Brothers and the beginning of the end of the Roman Republic This was the first sedition amongst the Romans, since the abrogation of kingly government, that ended in the effusion of blood. All former quarrels which were neither small nor about trivial matters, were always amicably composed, by mutual concessions on either side, the Senate yielding for fear of the commons, and the commons out of respect to the Senate. Plutarch on the beating death of the Roman tribune and reformer Tiberius Gracchus and his followers with “fragments of stools and chairs” by a Patrician mob at the capital in 133 BCE. 1) The Carthaginians had been defeated—what had been their empire (Spain, North Africa, Corsica, Sicily, & Sardinia) now belonged to Rome. And now, the year 133 BCE began a new age in Rome during which the dominant themes were internal DISORDER, VIOLENCE, and the quest for POLITICAL CHANGE. Before, the subject had been EXPANSION, wars of conquest and DEFENSE, and the development of Roman Government. Especially in the face of common enemies (e.g., the Gauls and the Carthaginians), there had been general agreement/cooperation at home between the various social classes; now the concerns were the continuance of the institutions of the REPUBLIC and the laws regulating the GOVERNMENT. 2) The rapid and sweeping changes which were the direct result of EXPANSION and CONQUERING were the root of the dissension; and now that a great common and unifying enemy had been subdued such a heavy strain was placed on the REPUBLIC that it began to rip apart. The root cause lay in the military RESOURCES required to manage this expansion and the stress that this placed on the traditional AGRARIAN lifestyle of the small Roman farmer who, though not owning much land, had a sufficient amount to qualify him for MILITARY SERVICE. 3) Rome thus became the first explicit example of the modern problem of URBAN UNREST directed against a narrowly-based OLIGARCHIC power structure; RIOTING and BITTERNESS among the CAPITICENSI were the result. This conflict, known as the ROMAN REVOLUTION, lasted for more than a century, and its course sank Rome into CIVIL WAR and finally ended with the overthrow of the REPUBLIC and the establishment of the IMPERIAL PERIOD under the Roman Emperors. 4) A time occurred during which the political factions (the OPTIMATE Senate and the POPULARIST Tribal Assembly of the Plebs) were gradually overshadowed by great leaders who used these factions to dominate the state in the name of ORDER & STABILITY; for the republic, this culminated when its last leader, GAIUS JULIUS CAESAR, gained its leadership and then was assassinated in 44 BC. 5) Next, there was a civil war between those leaders who tried to seize Caesar’s power (Octavian and Marc Antony); it ended with the establishment of a new form of government by Caesar’s grand-nephew Octavian, called (27 BCE) IMPERATOR CAESAR AUGUSTUS. Thus, the Roman IMPERIAL PERIOD had begun. And so, the dates for the period known as the Roman Revolution (the transition from REPUBLIC to IMPERIUM) are 133 BCE to 31-27 BCE). 6) THUCYDIDES’ analysis once again becomes relevant. Rome had lost those traits of character that made the REPUBLICAN form of government possible. Rome gave up its sense of fairness, moderation, and respect for Mos Maiorum. VIOLENCE and back-room deals became the SOP for running the government—when one disagreed with a political opponent one simply had him clubbed to death and the issue was resolved! 7) The beginning of the Roman Revolution is traditionally dated to 133 BCE and the GRACCHI brother’s efforts to bring about land reform. The land question was raised by Roman Tribune Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus, and, in doing so, he posed a serious challenge to SENATORIAL PRIVELEGES and the hold of land-based aristocrats over Romans who had been DISPLACED from their lands as a consequence of rendering military service to the REPUBLIC. 8) First, it is necessary to understand the institution of the Roman TRIBUNATE. After the expulsion of the last KING c. 509 BCE, the Romans maintained their SENATE (Council of ELDERS) which was comprised originally of the chiefs of the landowning family CLANS. While the Senate grew in PRESTIGE and AUTHORITY, it did not make any LAWS—it was more the sounding voice of the Roman conscience and patriotism and a refuge for the rich PATRICIAN class. Politically, although it was not a LAW making body, it’s domain included funding laws passed by the Tribal Assembly of the Plebs along with foreign affairs. 9) The Senate was led by two elected CONSULS whose combined authority replaced that of the single KING and who governed jointly for a term of ONE YEAR (limited tenure of office as per MOS MAIORUM) and typically were not re-elected. In the early republic, they resembled temporary KINGS who wore the imperial PURPLE toga and used an ivory chair. The Consuls also commanded Rome’s Armies. Consuls were elected from the SENATE and were lifetime Senators once their term expired; often they were made military governors of Roman provinces. 10) And so, how would the power of the consuls and the Senate COUNTERBALANCED? This was through an office invented by the early Romans: the TRIBUNES of the PEOPLE. The duty of the Tribune was to insure that the PLEBS (ordinary citizens) were not exploited by the two upper classes: the PATRICIANS who dominated the government and the priesthood, and the EQUITES, or Knights, who ran Roman businesses such as TAX FARMING. The Tribune’s authority was empowered by RELIGION, and so he needed no armed guard or escort to make an arrest. The penalty for attacking a tribune was DEATH. 11) A Tribune was prohibited from leaving the city of Rome, and his home needed to remain open DAY and NIGHT so that appeals could be heard. Initially, two Tribunes were ELECTED, then four, and finally TEN for terms of ONE YEAR. As the URBAN population grew, thy became VERY POWERFUL and could prevent consuls from enacting laws harmful to the Plebs by appearing and simply saying “Veto” (“I FORBID”). 12) It is important to keep in mind that the Tribunes themselves were PLEBIANS. And yet, they could sit in the Senate and participate in its DEBATES. They had the right to call the people to ASSEMBLY (the Tribal Assembly of the Plebs) and address them, and call for a VOTE even if the consuls disapproved. And so, the office of the Tribune was central to the definition of the ROMAN REPUBLIC as it provided a vital BALANCE between the PATRICIANS and the PLEBS. 13) As SMALL FARMS were coalesced into large estates because of Roman militaristic expansionism, free labor was replaced by SLAVE LABOR. Rome acquired a large number of unemployed, landless people—mostly returning VETERANS and their families--without enough property to qualify for military service. Much public land was traditionally held by the SENATORS. As TRIBUNE, Gracchus proposed re-dividing this land— much of it taken at the end of the 2nd PUNIC WAR, giving CLEAR TITLE to some of it to the NOBILITY, and have the rest revert to the STATE to be subdivided to the landless CAPITICENSI as HEREDITARY LEASES for payment of a small rent. It was a start: it took away no one’s rights and reverted to the old Roman policy of LAND DIVISION. Remember---what Gracchus was proposing was not a new law, but rather the ENFORCEMENT of a law that was already “on the books.” 14) Problem: GRACCHUS guessed that the SENATE would never relinquish their traditionally—and in principle ILLEGALLY--held lands. These lands had been in their families in some cases for generations; their DEAD were buried on them; they considered the lands to be THEIRS, not ROME’S. So, instead of taking the land reform legislation first to the Senate for advice as was required by MOS MAIORUM, T. Sempronius Gracchus instead took it first to the TRIBAL ASSEMBLY OF THE PLEBS; although this was his LEGAL RIGHT as TRIBUNE—it was SELDOM USED, and was without precedent for a bill of this magnitude. This “backdoor strategy” set the SENATE against Gracchus and the bill, but the masses were land-hungry, and it PASSED. This amounted to a DECLARATION OF WAR against the privileges of the SENATE. However, the senate refused to fund the bill, but Gracchus circumvented this problem by…. 15) Gracchus then took another unprecedented step by announcing an election since he needed to PROTECT his position in his office. This violated another fundamental principle of MOS MAIORUM: Limited Tenure of Office. This was the “final straw” for the SENATE. During a gathering of his supporters, Gracchus pointed to his head, signaling to his entourage to hold back the crowds. Senatorial spies in the room ran to the senate house and informed the senate that Gracchus was signaling for a crown. Immediately, A SENATE-INCITED mob led by SCIPIO NASICA fell upon Gracchus (then age 30) and 300 of his followers and clubbed them to death. Thus did the dignified fathers of the state, masquerading as the saviors of the REPUBLIC, degenerate to the level of a street mob; by their own violence they became the first to trample on law and order. The Senate now sentenced to DEATH those followers of Gracchus who had spoken of violence, while permitting NASICA to escape justice via exile on the pretense of conducting a diplomatic mission to Asia—where he quickly and conveniently DIED. 16) These events of 133-132 were EPOCHAL in Roman History. Selfish influence (again THUCYDIDES) had prevented the peaceful re-interpretation of the constitution to meet a new crisis. The result—at the time unseen, was the not-far-off DESTRUCTION of the Republic. Two bitterly opposed political parties, the OPTIMATES and the POPULARES, emerged from these events…. 17) The LAND LAW itself was not ended for FOUR YEARS. It did effective work in redistributing land ownership. In 10 more years, GAIUS GRACCHUS was elected TRIBUNE; he envisioned even broader reforms than his brother. But he, too, ran afoul of the SENATE because his reforms were unpopular. In 121, he was not re-elected as Tribune, and Senate attacked him—he committed suicide –in rigged trials the Senate executed 3000 of his followers in the subsequent PURGE. General Statement Regarding the Gracchi: They interpreted the issue of land reform too simply. They intensified class struggle; they did not create it. They were sitting on the lid of a pressure cooker that would have blown whether they had lived or not; the trouble lay deeper, in the failure (refusal) of the exploitive ruling class to create the necessary economic reform. The great menace to society is not the agitator, but rather those like the Senate who insist upon holding on to the status quo in an utterly changed society.